A startup promised EV jobs to struggling towns. TheyŌĆÖre still waiting.

A startup promised 45,000 EV jobs to struggling towns. TheyŌĆÖre still waiting.

They came with promises of transformation: thousands of jobs, surging salaries, and a foothold in the booming electric vehicle market.

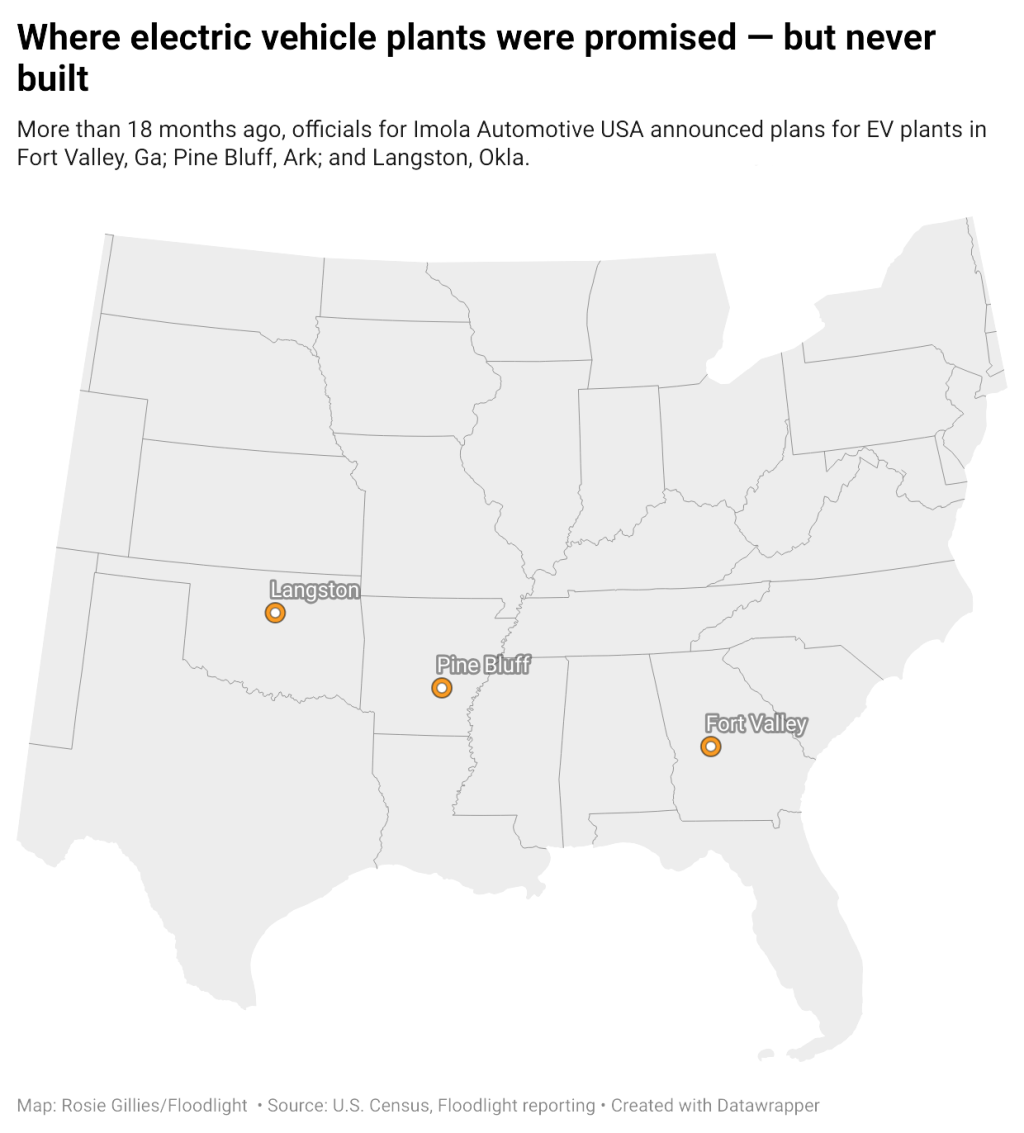

Imola Automotive USA, a Boca Raton, Florida-based startup, pitched officials in small, struggling towns in Georgia, Oklahoma, and Arkansas on a bold vision. The company planned to build six EV plants, create 45,000 jobs ŌĆö and help these impoverished communities secure a place in AmericaŌĆÖs green future, reports.

But over 18 months later, the company hasnŌĆÖt broken ground on a single site. And its top executive ŌĆö whose background is in television and athletic shoes, not automotive manufacturing ŌĆö has gone silent.

A Floodlight investigation did not uncover lost taxpayer money in Fort Valley, Georgia; Langston, Oklahoma; or Pine Bluff, Arkansas, where Imola has sought free land, municipal financing, and other incentives for its shifting proposals.

But an economic development watchdog said the episode illustrates how the frenzy to land electric vehicle jobs can leave economically distressed towns vulnerable to empty promises.

Imola CEO Rodney Henry declined requests for an interview. He responded to FloodlightŌĆÖs inquiries with a short statement, insisting the company had not given up on its plans, which have included a partnership with an Italian manufacturer of two-seat electric vehicles.

ŌĆ£Our timetable has been modified due to matters outside of our control,ŌĆØ Henry said in a statement. ŌĆ£We are highly focused on bringing our goals into alignment. Due to proprietary consideration as well as NDA (nondisclosure) agreements, we are not at liberty to discuss specifics at this juncture.ŌĆØ

ThatŌĆÖs a stark shift from the companyŌĆÖs earlier promises. In a press release issued in January 2024, Henry claimed the company had already secured land in multiple states to build half a dozen plants and create tens of thousands of jobs.

Could someone with no experience in car manufacturing really deliver that?

ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs ludicrous,ŌĆØ said Greg LeRoy, CEO of Good Jobs First, a nonprofit that tracks and analyzes economic development projects.

Building large auto plants, he said, requires ŌĆ£a great deal of capital, a great deal of management skill, a great deal of engineering and marketing chops. And obviously, Tesla developed those, but they didn't do it overnight, right?ŌĆØ

Langston, Fort Valley, and Pine Bluff werenŌĆÖt the only towns swept up in the competition to attract electric vehicle plants. Spurred by federal policies like the Inflation Reduction Act, which unlocked billions in private investment and expanded government incentives, local officials across the country scrambled to land high-paying manufacturing jobs and a slice of the booming clean energy economy.

Since the IRA passed in 2022, more than 150 EV plants have been announced in the United States, according to , a nonpartisan group of business leaders who advocate for economic development good for the environment.

But that rush may be grinding to a halt. The recently passed ŌĆ£One Big Beautiful Bill,ŌĆØ which rolls back many federal tax credits and incentives for electric vehicles, is already throwing the EV sector into turmoil ŌĆö threatening to stall or shrink the kinds of ambitious projects towns like Langston, Fort Valley and Pine Bluff were counting on. E2 reports that plans for 14 EV-related plants have been canceled this year.

Bold promises, then silence

In three towns where Imola pledged massive investment, thereŌĆÖs no sign of construction and little more than confusion.

Langston ŌĆö a town of 1,600 where more than 35% of residents live in poverty ŌĆö never saw ImolaŌĆÖs plans take shape.

A 2023 letter to the city council from former Imola chief operating officer Eric Pettus stated that the company had run into ŌĆ£multiple obstacles,ŌĆØ including trouble acquiring enough land.

ŌĆ£In order for us to continue moving forward on the project, we are requesting that the City of Langston convey to us any and all vacant properties owned by the city,ŌĆØ Pettus wrote.

Langston City Council member Magnus Scott said the company also asked the town to issue municipal bonds to help them build their plant.

But before any land changed hands or bonds were issued, a company representative delivered unexpected news: The deal had been canceled. ŌĆ£I guess maybe they ran into financial problems,ŌĆØ Scott said.

Reached by phone, Pettus, of south Florida, said heŌĆÖs no longer employed by Imola but instead works as a consultant for the company. Citing a nondisclosure agreement, he declined to discuss ImolaŌĆÖs plans.

Fort Valley gave its backing in early 2024 to ImolaŌĆÖs ambitious plan to build an EV plant that would employ 7,500 workers.

A year later, with no sign of progress on the plant, the company came back to the Georgia town with an entirely different proposal. This time, instead of building an EV plant, they pitched a high-tech lighting system for the town.

One city council member balked.

ŌĆ£You want us to sign an agreement for 99 years before you bring us the car company,ŌĆØ said council member Laronda Eason, according to minutes of the March 2025 meeting. ŌĆ£It feels like a bait and switch.ŌĆØ

Eason did not respond to emails and text messages seeking comment on the Imola proposal.

In Pine Bluff, where per capita income last year was just over $21,000, city officials were initially all in. Writing to Henry in August 2024, then-Mayor Shirley Washington said the city of 39,000 stood ready to buy land, build infrastructure, and issue industrial revenue bonds to support ImolaŌĆÖs vision.

ŌĆ£With an anticipated employment base of more than 8,000 jobs,ŌĆØ Washington wrote, ŌĆ£we firmly believe this investment will marshal a pivotal turning point in our community.ŌĆØ

But a year later, the project hasnŌĆÖt moved. ŌĆ£We never did get off the ground with that,ŌĆØ Washington said in a brief phone interview.

LeRoy said ImolaŌĆÖs pitch fits a troubling pattern.

ŌĆ£It grabs me as an example of how the craze among governors and mayors to get the next big thing has caused some sloppy vetting,ŌĆØ he said of the struggling communities courted by Imola.

Such towns, he said, are ŌĆ£easy prey. ŌĆ”TheyŌĆÖre desperate.ŌĆØ

Grand vision, missing details

Henry, who lives in Florida, touts a background as a longtime TV executive producer and the founder of Prot├®g├®, an athletic footwear brand. that Prot├®g├® donated a million pairs of shoes to African nations.

But despite announcements of partnerships and promises of good-paying jobs, his EV company has yet to show any tangible progress.

Floodlight found the website for Imola ŌĆö named after the Italian city where Tazzari EVs are made ŌĆö is no longer accessible without a password. A search of the Tazzari website found no mention of plants in the United States. But a 2024 version of the Imola site mentions the tiny vehicles ŌĆ£coming soon to America.ŌĆØ

In early 2024, Imola Automotive USA and the Tazzari Group ŌĆö an Italian firm best known for its electric two-seater micro cars ŌĆö jointly announced plans for a partnership.

The EVs that Tazzari makes in Italy arenŌĆÖt designed for highway driving. Top speed on the companyŌĆÖs Opensky Sport model is about 56 miles per hour, while maximum speed on the Opensky Limited is about 37 mph, according to .

Tazzari didnŌĆÖt respond to email messages from a Floodlight reporter.

Henry said at that time that the company chose Langston and Fort Valley because of their universities.

ŌĆ£Both of these locations are ideal,ŌĆØ he said in the January 2024 news release, ŌĆ£as their proximity to communities with institutions of higher learning, will allow residents and students career opportunities in the fast growing EV Technology and Innovation Industry.ŌĆØ

Many local officials in Fort Valley, Langston and Pine Bluff did not respond to interview requests. Few documents were provided in response to FloodlightŌĆÖs public records requests.

But itŌĆÖs clear from available records that ImolaŌĆÖs promises stirred hope.

Langston Mayor Michael Boyles called the proposal ŌĆ£transformativeŌĆØ in a January 2024 news release.

But some local leaders soon began to question the details.

Erica Johnson, a real estate agent and former member of LangstonŌĆÖs economic development commission, said parts of the plan didnŌĆÖt add up. How, for instance, would the company house more than 1,000 workers in such a small town? And how were they going to build such a large plant on land without utilities or water?

Her doubts deepened when she learned that Imola wanted to lock down land agreements without putting up any earnest money.

ŌĆ£My early feeling was that, ŌĆśSomething is not quite okay with this,ŌĆÖ ŌĆØ she said. ŌĆ£But I think the hope for our community kind of outweighed the ability to just take things slow and look at them for where they are and what they are ŌĆö versus where you hope them to be.ŌĆØ

Eventually, the promise fizzled.

ŌĆ£It was disappointing,ŌĆØ Johnson said. ŌĆ£...We could have had our energy and time focused on something that seemed more valid and more substantial.ŌĆØ

Still waiting for the shovels

Some residents in Fort Valley are still holding out hope.

Mayor Jeffery Lundy said early last year that it was a ŌĆ£priority for my administration to land a company like Imola Automotive USA.ŌĆØ Local officials, he said, were looking forward to the economic boost the plant would bring.

At the time, Imola claimed it would break ground on a 195-acre site by the third quarter of 2024 and open the plant within 20 months, according to a report in .

During a February 2024 town hall meeting, Imola officials told residents that the plant would pay employees an average of $45 an hour, Commenters buzzed with excitement, with one writing: ŌĆ£Application me !!!!ŌĆØ

Pettus that most jobs would require only a high school diploma.

In early 2024, Fort Valley rezoned land to accommodate the plant, and the city council signed off on the deal. But more than 15 months later, thereŌĆÖs still no sign of construction.

Council members were told that Georgia Power couldnŌĆÖt provide sufficient power for the EV company, according to minutes of their March 2025 meeting. A spokesman for Georgia Power said that while the utility doesnŌĆÖt discuss economic development projects, ŌĆ£WeŌĆÖre prepared and ready to meet the energy needs of any new customer.ŌĆØ

Makita Driver, one of the Facebook commenters whoŌĆÖd voiced excitement about the proposed EV plant, said thereŌĆÖs no doubt she would have applied for one of the jobs there ŌĆö had the facility ever been built.

ŌĆ£The pay rate was really what got my attention,ŌĆØ she said.

As a medical assistant, Driver said she earns far less than what Imola had promised. But she eventually concluded the promises were too good to be true.

ŌĆ£Who really makes that kind of money starting out?ŌĆØ she asked.

In a brief interview with Floodlight on July 11, Mayor Lundy said heŌĆÖs still in contact with Henry.

ŌĆ£We are patiently waiting for that groundbreaking,ŌĆØ Lundy said.

is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates the powers stalling climate action.

was produced by and reviewed and distributed by ┬ķČ╣įŁ┤┤.