For decades, the Feds were the last, best hope for special ed kids. What happens now?

For decades, the Feds were the last, best hope for special ed kids. What happens now?

Last December, after a year and a half of blind alleys, impenetrable paperwork and bureaucratic stonewalling, it seemed like the complaints Sierra Rios had filed against her fifth-graderÔÇÖs elementary school were finally getting a proper investigation. A lawyer in the Dallas office of the U.S. Department of EducationÔÇÖs Office for Civil Rights was asking hard questions of the school where Rios said her daughter, Nevaeh, was repeatedly denied special education services.

But then, a few weeks into the probe, the San Antonio mother got a bounce-back email informing her that the attorney working on her case was no longer employed by the agency. As part of its plan to shutter the department, the Trump administration had fired 40% of the civil rights divisionÔÇÖs staff and closed half of its regional offices.

The March email did not say what would happen to RiosÔÇÖ case. In May, she got a message asking for a form that had somehow not been transferred from Texas to the agencyÔÇÖs office in Kansas City, Missouri. Rios resent the document, but it no longer mattered. During the churn, she was told, the complaint had become too old to pursue.

The saga is a vivid illustration of the awaits families of students with disabilities. For decades, the federal government has been a key avenue of relief for parents unable to get services for their children through complaints filed with their state, mediation, administrative hearings or due process cases. Now, with the department lurching toward closure, state-level officials may increasingly have the final word. And an analysis by shows that those systems, intended to help desperate parents like Rios, have never delivered on their promise.

A ÔÇÿparent-friendlyÔÇÖ process thatÔÇÖs anything but simple

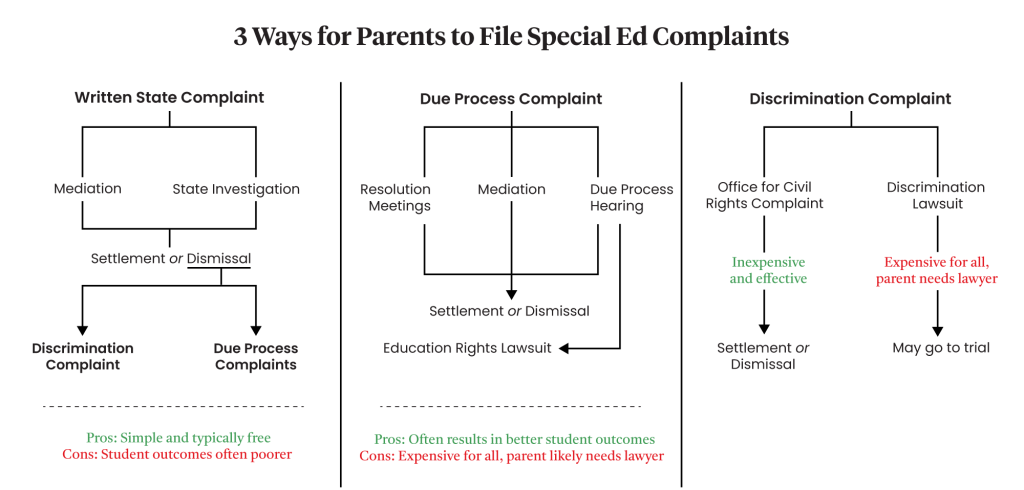

Fifty years ago, under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, Congress created three ways parents could appeal to their state education departments if they felt their children were being denied accommodations in school. These mechanisms vary in complexity and effectiveness, but all were supposed to be simple enough for any parent to navigate.

Families, or school administrators seeking help in resolving a disagreement, can file a complaint with their state in hopes that education officials will intervene if they find a districtÔÇÖs efforts lacking or improper. Parents can also ask the state to appoint a mediator who will try to bring both sides to an agreement. Most complicated, but potentially most effective, families can file a due process complaint, which kicks off a legal process that usually requires an attorney or skilled advocate. The complaint may start with a mediator but can progress to a formal hearing before an administrative law judge. If the dispute isnÔÇÖt resolved there, the case can turn into a federal lawsuit.

Some states pursue complaints quickly, with an eye toward resolving issues before they become intensely adversarial and expensive. Others lag or throw up procedural roadblocks, presumably trying to reduce the number of cases filed.

Complaints can run aground at . The length of time a family has to file after the event theyÔÇÖre disputing differs depending on where they live and which mechanism theyÔÇÖre trying to use. If an email or letter doesnÔÇÖt get a reply within a certain number of days, the case can be closed. Things must be done in a precise order, spelled out in legalese.

In RiosÔÇÖ case, she initially tried to open a state complaint against the principal of NevaehÔÇÖs school in 2023. The Texas Education Agency rejected her request in a letter that she read as saying complaints cannot be filed against individuals, just schools and districts. (The agency says complaints can be filed against individuals.)

Rios assumed her complaint was dead in the water. A year later, with NevaehÔÇÖs situation deteriorating as school staff, Rios says, grew tired of the familyÔÇÖs continued complaints, she did more research and opened a case at the Office for Civil Rights under the Americans with Disabilities Act.

The law that created the state complaint processes, the IDEA, guarantees disabled studentsÔÇÖ educational rights. By contrast, the ADA, passed in 1990, outlaws discrimination against people who need accommodations to access public facilities and programs ÔÇö including schools.

Families of children denied special education services can assert their rights under either law. When states fail to enforce a studentÔÇÖs educational rights under IDEA, families often file a discrimination complaint via the ADA.

In the 2022-23 school year, more than 54,000 state were filed in the U.S. and its territories, including due process complaints, written state complaints and mediation requests. The Office for Civil Rights had ÔÇö half of them involving disability discrimination ÔÇö when its staff was . For fiscal year 2026, which started July 1, the White HouseÔÇÖs proposed OCR budget is $91 million, a 35% drop.

At the same time, the administration wants to move $33 million that currently funds state advocacy clearinghouses into block grants that states ÔÇö cash-strapped as their federal pandemic funds run out ÔÇö can use for other things. This means families risk losing a second source of leverage: free assistance from experts.

If enacted, both budget cuts would also exacerbate socioeconomic and racial disparities in the services kids with disabilities receive, says Carrie Gillispie, a senior policy analyst at New America. This is because families in states where thereÔÇÖs little appetite for local enforcement depend on OCR to investigate discrimination.

ÔÇ£Those discrepancies that exist if these budget changes happen,ÔÇØ Gillispie says. ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs a choice to continue to underinvest.ÔÇØ

With the federal office a hollow shell of what it was six months ago, advocates say, families are likely to rely more heavily on their states. And how ÔÇö and how well ÔÇö each state helps students with disabilities varies widely.

In fact, The 74ÔÇÖs analysis found great geographic disparities in the kinds of appeals families pursue and how far they make it in the multistep processes. In the few places that have more than a handful of special education lawyers, primarily on the East and West coasts, due process cases often dominate. In the Midwest, where there are few or even no special ed attorneys or advocates, families must go it alone, and public officials frequently put up roadblocks to impede complaints parents file with their states. Here, there are fewer disputes ÔÇö likely because parents often depend on schools to apprise them of their rights ÔÇö and complaints are less likely to end in a written agreement.

Information collected by the U.S. Education Department does not record whether outcomes are favorable for students. But attorneys and advocates say that for those who have access to expert help ÔÇö either for a fee or pro bono, through an advocacy group ÔÇö a due process complaint can yield a quick settlement from a district looking to end a familyÔÇÖs case and move on.

Using state data submitted to the department from the 2014-15 academic year through 2022-23, the most recent available, the interactive map above shows how many cases are filed in each state and how they compare with the national average. The rate of due process complaints per 10,000 children identified as qualifying for special education services in each state has been tabulated to account for population differences.

In addition to national averages, we focused on four localities ÔÇö , , and the ÔÇö that illustrate different approaches to resolving disputes and how far in the process they proceed, and included an interactive chart for each.

The process was , and to allow parents and schools to start with the least contentious, simplest and most inexpensive options. With some exceptions, a family can begin by filing a written state complaint or by requesting mediation, and, if no agreement is reached, open a due process case later on. If one side disagrees with the decision in a due process hearing, it can file a federal suit. In some circumstances, the losing party will be ordered to reimburse the other sideÔÇÖs attorney fees.

This analysis excludes two statistical outliers: New York, where, because of a tangled legal history, two-thirds of recent complaints in the U.S. were filed; and Puerto Rico, where students are protected by federal law but the special education system is unique.

Finally, researchers looked at trends in Texas, where advocates are cautiously optimistic that a decade-old federal intervention has nudged the process closer to CongressÔÇÖ original vision. Advocates say changes made by Texas officials are getting families what they need faster, and with less red tape, all with an eye to heading off the most contentious options.

Barring similar efforts by districts and state education officials to help families before disagreements become adversarial, advocates predict the system will become more litigious. By definition, that will make it more expensive for everyone involved, as districts and families are forced to spend money on attorneys and experts instead of the services children need. In June, the U.S. Supreme Court issued a decision making it to file federal discrimination suits.

The upshot, advocates say, could be an even more inequitable playing field, where families with access to attorneys and the ability to pay them have leverage and those who donÔÇÖt are at the mercy of their statesÔÇÖ willingness to enforce their rights.

Each process for resolving special education disagreements comes with major trade-offs ÔÇö which are typically unclear for families trying to figure out where to start.

A written state complaint is usually the easiest route for a parent going it alone. ItÔÇÖs free. The information needed to start is comparatively straightforward. The law requires states to finish investigations within 60 days, which is months or years faster than the alternatives.

If, at any point, a parent and district come to an agreement, they can simply stop the process. If the state probe goes forward, a finding is issued. published in 2018 in the Journal of Special Education Leadership, a survey of district leaders the year before showed that 62% of state investigations that played all the way out concluded that a district was not compliant with the law.

Caveats abound, however. In many places, state complaints canÔÇÖt be appealed. A mediator or state investigator can determine that a student is owed compensatory services ÔÇö academic or therapeutic time to make up for interventions they were improperly denied or money to pay for private services. But in practice, they rarely result in financial compensation for a studentÔÇÖs family.

Though these agreements are often supposed to be legally binding, they donÔÇÖt always carry the weight of a legal judgment, so schools can feel little pressure to make meaningful changes.

Finally, in order to get what their child was denied, families often must sign a nondisclosure agreement. This makes it hard for parents to compare notes about what services are available from their school and what they can reasonably ask for.

In , families told the Council of Parent Attorneys and Advocates ÔÇö a network of state and local professionals partly funded by IDEA ÔÇö that the corrective actions called for in state findings are often inadequate and ignored by schools, with no state follow-up to ensure compliance. Parents also complained that state investigators are sometimes quicker to believe districtsÔÇÖ stories than familiesÔÇÖ, even in the absence of evidence. Mediators may fail to help parents and schools reach an agreement.

By contrast, filing a due process complaint is not unlike filing a lawsuit. Indeed, if a disagreement isnÔÇÖt resolved at a negotiation called a resolution meeting or by a mediator, an administrative law judge takes testimony, considers evidence and issues a ruling. If that does not end the dispute, either party may ÔÇö provided it has the resources ÔÇö continue the case in federal court.

But parents often donÔÇÖt have the money to hire an attorney or advocate to take the case. Some states have just one lawyer who will accept special education cases. In part, this is because a family must win to have just its attorneyÔÇÖs fees covered. In addition, in most instances, plaintiffs canÔÇÖt hire experts to counter testimony given by district witnesses.

Until recently, anyway, lodging a complaint with the OCR instead of the state was often parentsÔÇÖ most attractive option.

Families in rural areas rely on state complaints for solutions

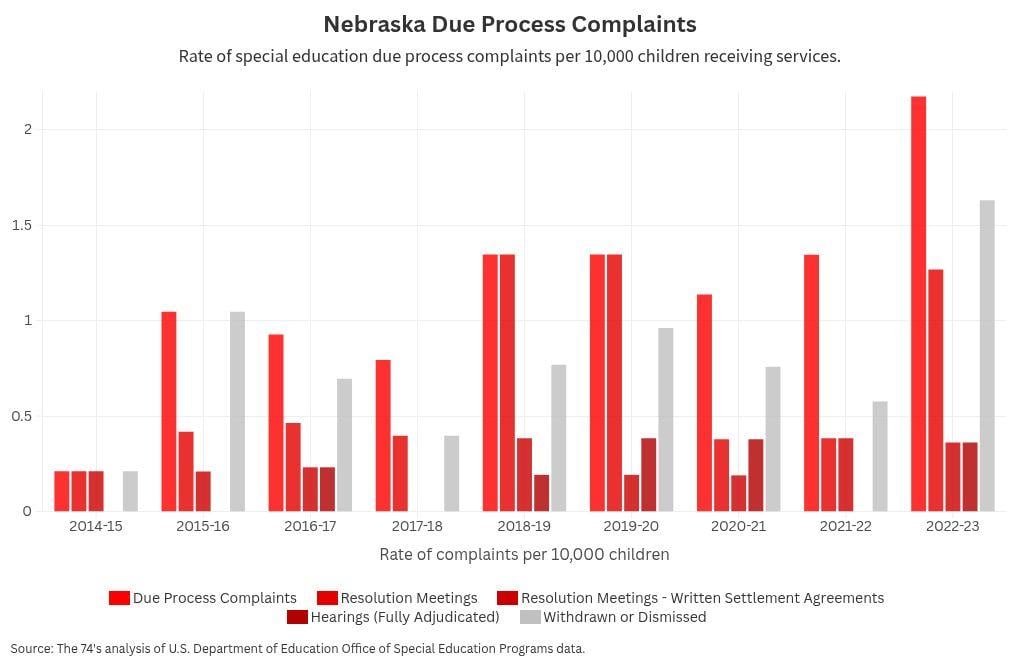

In many rural states, such as Nebraska, families rely on written state complaints when their kidsÔÇÖ needs arenÔÇÖt being met. Dispute resolution filings are rare because advocates and attorneys are few and far between, and the number of due process cases is low.

State complaints are supposed to be the fast, easy, least costly and least adversarial path to getting kids services without the expenses of hiring an attorney. But outcomes are often poor.

ÔÇ£They are especially good for clear procedural violations that may impact the student,ÔÇØ says Amy Bonn, an Omaha-area attorney. ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs basically saying, ÔÇÿHereÔÇÖs where the district did something that did not comport with the actual law.ÔÇÖÔÇØ

When IDEA was created, Congress envisioned the state complaint system to be the ÔÇ£most powerful and accessible option for parents,ÔÇØ but it often falls short in resolving noncompliance issues, according to a from the Council of Parent Attorneys and Advocates.

The organization stated in its that the system is ÔÇ£an often ineffective process that lacks transparency, impartiality and accountability by state educational agencies charged with administering the dispute resolution process.ÔÇØ

Once a complaint is filed, the investigation is in the stateÔÇÖs hands ÔÇö and out of the parentsÔÇÖ. Any decisions, including corrective actions, are made by the state within a 60-day timeline, and they usually canÔÇÖt be appealed.

ÔÇ£[Families] might get relief or they might not, but there are no judges or a hearing,ÔÇØ says Kathy Zeisel of the ChildrenÔÇÖs Law Center, an agency that takes cases and connects families with pro bono lawyers to file complaints. ÔÇ£You get systemic change, such as a district having to change policies,ÔÇØ instead of an accommodation to help a particular student.

But debates between families and school districts about special ed services that were not delivered during the COVID pandemic have begun to change the landscape, Bonn says. An increase in the number of parent advocates and lawyers who take special education cases has led to more filings in recent years.

ÔÇ£I think the culture is changing a little bit,ÔÇØ Bonn says.

Due process comes with steep costs and barriers

With the federal backstop of the Office for Civil Rights disappearing, even more due process complaints are likely. They are expensive for both families and districts but effective ÔÇö when the process is accessible to parents.

Here are two examples of how this is playing out in states where the number of these complaints is rising quickly.

In California, the dispute resolution process is available to financially stable, highly educated families confident enough to speak out about their childÔÇÖs services, says Cheryl Theis, who worked as a parent advocate in Oakland for 18 years at the Disability Rights Education Defense Fund.

ÔÇ£IDEA is built on one fundamental premise: that every child has a parent who can advocate for them,ÔÇØ Theis says. ÔÇ£But thereÔÇÖs always been some power imbalance around how effectively a parent can participate and how hard theyÔÇÖre willing to push, and thatÔÇÖs been an ongoing problem.ÔÇØ

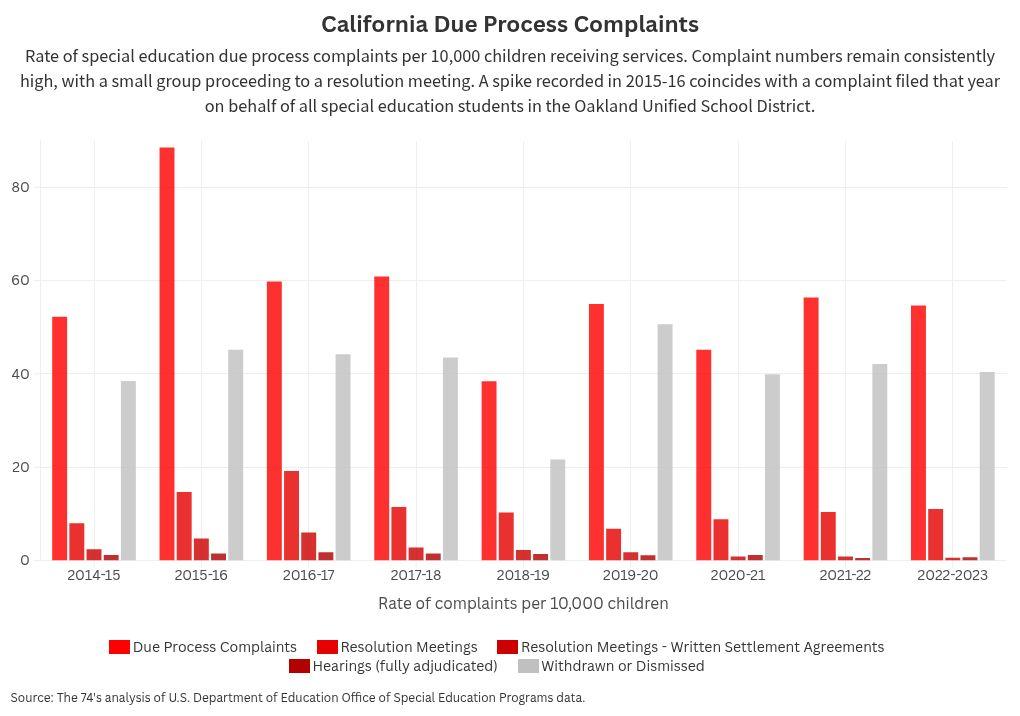

Over the past several years, California has received roughly the same number of mediations and due process complaints ÔÇö which make up about 90% of filings, according to data from . The state had nearly 55 due process complaints and 56 mediation requests per 10,000 children in 2022-23.

Excluding the outliers not included in this analysis ÔÇö New York and Puerto Rico ÔÇö CaliforniaÔÇÖs due process case rate is the second highest in the country. But the number of cases that proceed to the ultimate stage is minuscule. Less than 1% of the 4,401 cases filed in 2022-23 were heard by a judge, while 3,254 were resolved before the hearing stage.

Advocates say this reflects a trend they expect to play out in other places: With large numbers of private law firms and nonprofits able to file pro bono cases, increasingly, school districts are choosing to settle due process complaints quickly. Many California school systems now routinely purchase commercial insurance, which picks up most of the cost. This may seem like an inexpensive way to shorten what can be months of expensive arguments, but attorneys and disability advocates note that the insurance premiums come out of the districtÔÇÖs budget, which could be paying for needed services.

Some families end up with better agreements for their children than they would using the state complaint process, advocates say. But even when families view a settlement as a win, Theis says, compensatory education often requires the parent to pay upfront for private services and get reimbursed from the district ÔÇö another barrier for those who are on a low income.

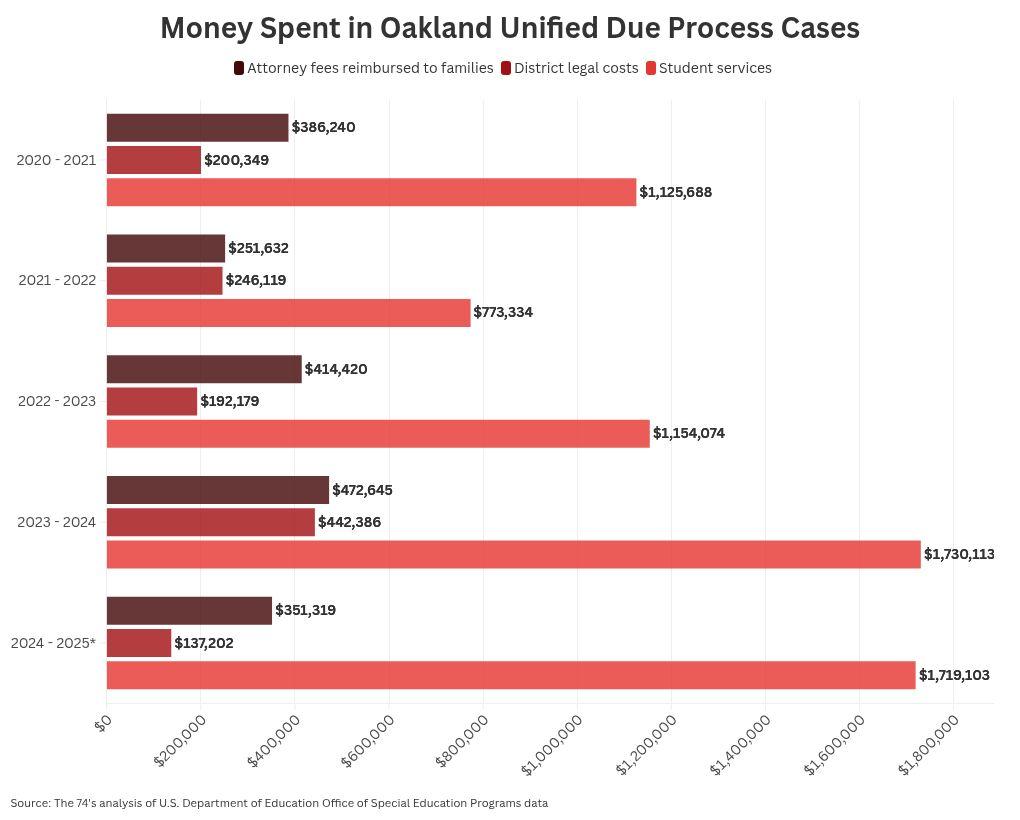

In the past two school years, Oakland Unified School District shelled out $579,588 in attorney fees and paid $823,964 to families to cover their legal costs in settlement cases, according to district financial records. The settlements forced the district to spend roughly $3.5 million on student services.

Oakland in previous years for IDEA violations. Systemic problems uncovered by investigations in 2007 and 2013 included staffing shortages, lack of special education curricula, deficient budgets and the placement of students in segregated special ed classrooms, according to Disability Rights California.

The nonprofit filed a on behalf of all special education students in the district.

ÔÇ£If you look at those millions of dollars in settlements, like, how many teachers could you train, how many adaptive tricycles could you buy? What specialized summer programs could you create?ÔÇØ Theis asks. ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs like this squeaky-wheel system where 10 people might need it, but only one parent is going to have the knowledge, the time and the finances to maybe get an attorney.ÔÇØ

In a statement the district said that since the pandemic, it has expanded its alternative dispute resolution program, which provides a neutral representative who can conduct IEP meetings or resolve issues with families without an attorney or legal fees.

ÔÇ£Additionally, we offer open office hours monthly for any family who wants to speak with a neutral special education attorney about their questions or concerns about their childÔÇÖs IEP,ÔÇØ the district said.

In 2024-25, 31 cases went through the alternative dispute resolution program, and 29 were resolved with no attorney fees, the district said.

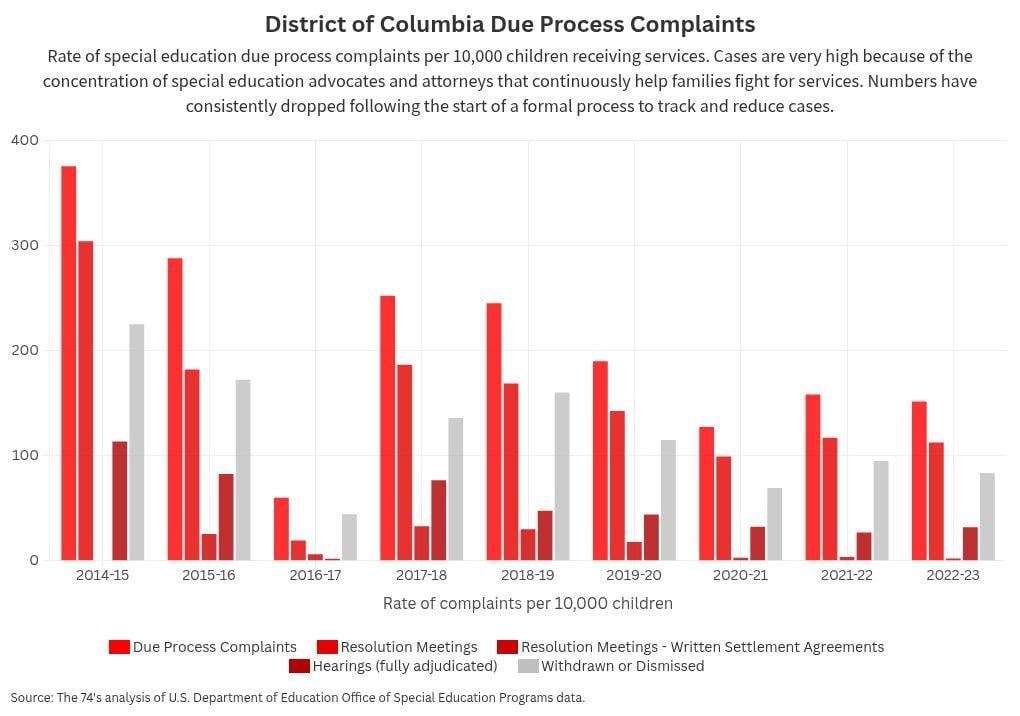

The second example, Washington, D.C., has one of the highest rates of due process complaints in the nation, behind New York and Puerto Rico. In 2022-23, roughly 151 complaints were filed per 10,000 children. These numbers in March to investigate claims that D.C.ÔÇÖs traditional public school system is not meeting the needs of students with disabilities.

Advocates say D.C.ÔÇÖs special education issues are similar to those in the rest of the nation, but an oversaturation of disability lawyers and agencies has educated families about their childrenÔÇÖs school services ÔÇö and taught them to use litigation to get what they are entitled to under federal law. This, they say, contributes to the high filing numbers.

A from the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights found that D.C. has the highest rate in the nation of due process complaints resolved without a hearing, which could indicate a ÔÇ£sue and settle approachÔÇØ ÔÇö which favors those who can afford attorneys.

ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs really a national problem that we are just disregarding kids with disabilities and not putting the resources into them,ÔÇØ says Zeisel, whose ChildrenÔÇÖs Law Center has roughly 250 cases at any given time, one-third involving families going through due process. ÔÇ£Parents have to sue, and kids lose almost a whole school year to try to get what [they need]. We would love to put ourselves out of a job and not be litigating this stuff and go do something else.ÔÇØ

While advocates say the number of cases is still too high, D.C.ÔÇÖs filing numbers have plummeted over the last decade. In the 2011-12 school year, 805 due process complaints per 10,000 children were reported. The latest data available shows that D.C. had 151 complaints per 10,000 children in 2022-23.

The credits the drop to D.C. improving its capacity in handling cases and creating a student hearing office.

In 2023, the city paid more than $3.1 million to attorneys as a result of due process complaints against D.C. Public Schools, according to a 2023 inspector general .

Donovan Anderson represented the district in special education cases until he opened his own firm doing the same work more than 25 years ago.

ÔÇ£Parents will reach out to me because they are searching for answers,ÔÇØ he says. ÔÇ£They are in disbelief with the quality of education that their child is receiving.ÔÇØ

Once Anderson files a on behalf of a family, the district has 15 days to hold a resolution meeting as a way to discuss the issues and potentially resolve them. He says almost all his cases end at this stage because continuing with due process is usually time-consuming and too costly for families.

If nothing is agreed upon during the resolution meeting and a parent wants to continue to a due process hearing, the timeline can stretch to 75 days before any decision is made. Then thereÔÇÖs also more of a chance that families will lose their case and come out with nothing but debt after a long fight.

Anderson says resolving a case during the resolution meeting makes the school district pay the familyÔÇÖs attorney fees ÔÇö usually a few thousand dollars ÔÇö but parents who lose due process are on the hook for the thousands more spent on lawyers and experts to testify during the hearing.

ÔÇ£If I settle the case in 15 days, the child [and] the parent can see tangible results in 30 to 45 days after meeting me,ÔÇØ he says. ÔÇ£I can make a lot more money if I have to go to a due process hearing, but it doesnÔÇÖt necessarily benefit the child, because the parent has to wait that much longer to have tangible solutions.ÔÇØ

ÔÇÿThe therapist said it was self-defenseÔÇÖ

Even the most cut-and-dried due process case ÔÇö the kind likely to be resolved quickly and in a studentÔÇÖs favor ÔÇö can be prohibitively expensive just to file. Texas parent N.G.ÔÇÖs son, A.G., is autistic, nonverbal and very bright. (Because the family signed a nondisclosure agreement at the conclusion of the case ÔÇö a common district demand ÔÇö N.G. asked that they be identified by their initials.)

A.G. could add and subtract in kindergarten, but his first-grade teacher conflated his lack of speech with academic incompetence and gave him a picture of the number one to color. Bored, A.G. acted up, his mother says. A few weeks into the year, he wandered off and got lost in the school.

In February, he came home with a hand-shaped bruise on his arm following an occupational therapy session in school. ÔÇ£The therapist said it was self-defense,ÔÇØ N.G. says. ÔÇ£I said, ÔÇÿHeÔÇÖs 6 and he has low muscle tone.ÔÇÖ ÔÇØ

It took her a month to find an attorney, hundreds of miles away. The lawyer charged a flat fee of $6,000 for his first three months of work. The familyÔÇÖs due process complaint was so stark and well-documented ÔÇö N.G. had logged every interaction on a spreadsheet ÔÇö that a mediator quickly negotiated a good settlement.

Had the mediator failed, however, the family would have had to drop the complaint. After 90 days, the attorney would have needed to be paid by the hour ÔÇö money N.G. would not necessarily have been entitled to recover.

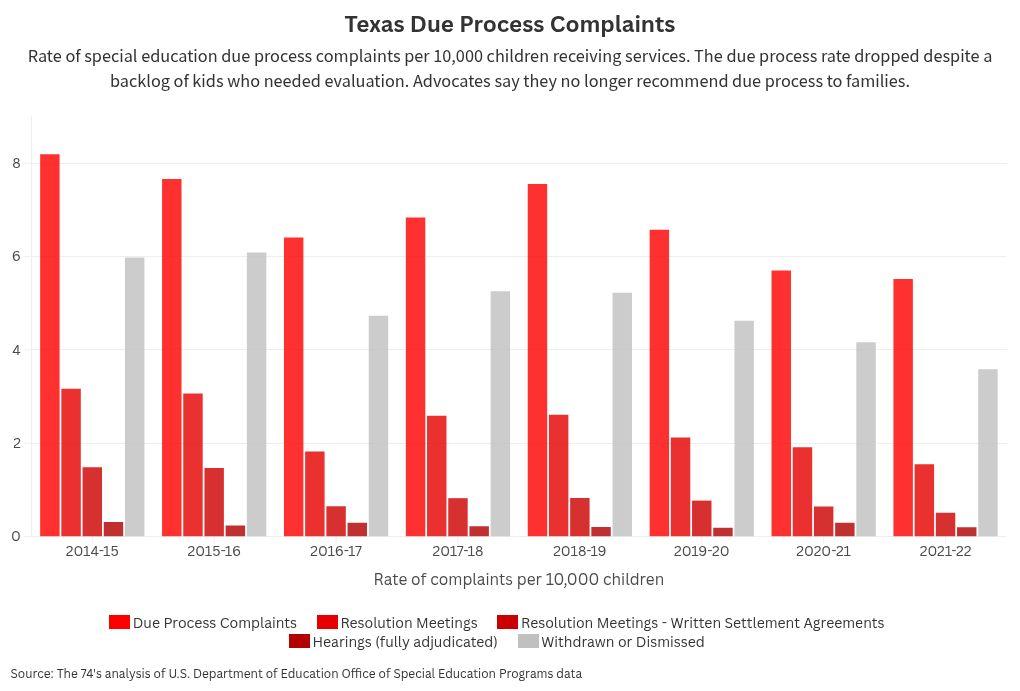

Perhaps the best proof of the value of federal oversight of special education is to be found in Texas, where state officials have spent seven years overhauling how schools are held accountable for serving children with disabilities. Attorneys and advocates now routinely advise families to avoid due process altogether and file state complaints ÔÇö the route Congress originally envisioned as the quickest path to securing help for kids.

In 2016, a revealed that for years, the state had improperly denied services to hundreds of thousands of children by capping the number of special ed students districts could serve. In response, the U.S. Education Department ordered state officials to take a series of steps to find and evaluate children with disabilities.

Since then, the number of special education students has increased by 67%, rising from 463,000 to 775,000. Meeting their needs has stretched Texas schools, which couldnÔÇÖt simply conjure the staff ÔÇö or funding ÔÇö to beef up special education overnight.

In 2022, Texas lawmakers lengthened the amount of time families have to file due process claims from one year after an episode to a more standard two years.

Conventional wisdom would hold that a tsunami of families seeking support and a longer window to complain when they donÔÇÖt get it would send caseloads skyrocketing. But due process complaints have instead fallen, from 8 per 10,000 students in 2014-15 to 5.5 in 2021-22.

Meanwhile, the number of state complaints nearly quadrupled between the 2020-21 and 2022-23 academic years, rising from 261 to 979. The number of resulting reports ÔÇö the documents that say what state investigators found ÔÇö tripled, from 164 to 549. Also on the rise is the number of complaints withdrawn before the formal process begins ÔÇö likely as a result of districts resolving disagreements quickly.

Colleen Potts, supervising attorney for Disability Rights Texas, says the organizationÔÇÖs lawyers now see state complaints as the most effective way to get quick relief for students and families.

ÔÇ£IÔÇÖve been doing this for 19 years, and the last two or three years we are getting consistently good outcomes in non-adversarial ÔÇÿmeeting of the mindsÔÇÖ meetings, with resolutions that are acceptable to everyone,ÔÇØ she says.

Indeed, districts often are quick to try to resolve disagreements before the state investigates. Potts encourages the attorneys she works with to list proposed remedies in their complaints, even if they arenÔÇÖt things a state typically requires a lagging district to do.

In practical terms, this document can serve as a road map to getting a childÔÇÖs needs met, she explains: ÔÇ£Anything is on the table.ÔÇØ

In 2018, in response to the U.S. Education DepartmentÔÇÖs intervention, the Texas Education Agency drew up an for overhauling special education statewide. A key goal was making resources available to families and districts to help them resolve disagreements early. According to Jennifer Alexander, TexasÔÇÖ deputy commissioner for special populations and student supports, 10% of state complaints are now resolved this way, even if investigators have already begun work on the case.

As the state officials made the changes outlined in the strategic plan, they examined data on disputes to find out where things go awry, says Alexander: ÔÇ£Where it often breaks down is the family does not know the process and so canÔÇÖt express to the district what they need.ÔÇØ

To that end, in 2023 the state began offering to pay for trained facilitators to participate in the initial meetings where families and educators negotiate a childÔÇÖs individualized education program ÔÇö the legally required document that spells out how the studentÔÇÖs needs will be met. The cost to the state is $1,500 per negotiation.

Of the 20 facilitated IEP meetings that took place in 2024, 40% resulted in an agreement, Alexander says. During the first half of 2025, there were 25 meetings, and 56% have resulted in agreements. Two negotiations are pending.

The state also created a parent-friendly special education online portal, , where a relatively simple automatically collects the information that is legally required to make a case pursuable, to head off situations like RiosÔÇÖ.

When the form is submitted, the district immediately gets a copy. This, Alexander says, often prompts school staff to begin trying to resolve the disagreement. Any agreement is legally binding.

The changes Texas has made are having an impact for students, advocates agree. And, they say, there is reason to hope that the new strategies for ironing out disagreements before they become heated will show other states that better, quicker communication can head off the costs faced by places like Oakland and Washington, D.C.

But without the possibility that federal officials will compel states to do better, any improvement will be piecemeal, says Robyn Linscott, director of family and education policy at The Arc of the United States.

ÔÇ£You might have some states that try to step in and create or beef up a state-level backstop, whether itÔÇÖs a special agency or ombudsman or something they already have in place,ÔÇØ she says. ÔÇ£And then youÔÇÖll have other states that are not necessarily going to see the value in trying to provide more stable resources for families to have recourse.

ÔÇ£This will leave us with this state-by-state patchwork.ÔÇØ

Uncertainty remains for parents who fight for their childÔÇÖs services

According to documents filed in a court case challenging the Trump administrationÔÇÖs mass firings, the U.S. Education Department said it dismissed more than 3,400 complaints between March 11 and June 27, . ThatÔÇÖs more than 28% of the OCRÔÇÖs caseload.

Rios has yet to learn whether hers is one of them. After the May email informing her the case had been closed because it was too old, an advocate helped her compile a paper trail showing she had met every deadline. In the past, that has often convinced the agency to make an exception.

Rios says all she wants is what sheÔÇÖs been fighting for this entire time ÔÇö accountability from the school and a plan to make it right for Nevaeh.

ÔÇ£She goes to school and she learns, but then she comes home and IÔÇÖm reteaching the material,ÔÇØ Rios says. ÔÇ£On top of all of that, IÔÇÖm now having to file complaints, follow up on complaints, send angry emails, follow up on those angry emails, make phone calls ÔÇö like, IÔÇÖm basically my daughterÔÇÖs teacher, lawyer, advocate, IÔÇÖm everything.

ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs a lot. I feel like there [are] programs and there are laws around these things for a reason.ÔÇØ

was produced by and reviewed and distributed by ┬ÚÂ╣È¡┤┤.