Before special ed, there was the school-to-asylum pipeline. How one lawsuit helped end it

Before special ed, there was the school-to-asylum pipeline. How one lawsuit helped end it

The moment, Thomas Gilhool would tell a historian decades later, āseemed providential.ā

It was 1969. Two men from the Pennsylvania Association of Retarded Children made an appointment to meet with the young lawyer with a reputation for taking pie-in-the-sky cases more experienced attorneys wouldnāt touch. Gilhool was five years out of Yale Law School, practicing out of an office that was no wider than his desk ā barely large enough to receive the visitors.

Wedged in sideways, the men handed him a report they had commissioned on conditions at the Pennhurst State School and Hospital, the stateās notoriously overcrowded asylum for the mentally retarded. They were hoping to use the courts to better the lives of the people confined there. (In the interest of historical accuracy, in portions of this article, uses terminology now recognized as offensive.)

Gilhool had never heard of the organization, now known as The Arc of Pennsylvania, but he knew more than most people about Pennhurst. At the time, children could be deemed retarded for a host of reasons: for having an intellectual disability, but also for seizure disorder, cerebral palsy, birth defects, bad behavior, or even not speaking fluent English.

Public school was often the first stop on a short path to institutionalization. Children would enroll, quickly be deemed āineducableā and consigned to places like Pennhurst, where forced labor, neglect and violence often cut their lives short.

Gilhoolās brother Bob had been committed to the asylum, the attorney told his stunned guests.

By the meetingās end, Gilhool had taken the case ā never mind that the three were still uncertain exactly what the case would be. The lawyer asked for a little time to think. Nine months later, he reappeared, grand design in hand.

Eventually, they should ask the courts to close the facility. But the first task, Gilhool told his new clients, was to establish disabled childrenās right to an education.

Prohibiting schools from using asylums as dumping grounds was the initial step toward shutting down the pipeline of new residents and triggering the creation of alternatives ā including the classroom instruction that would help children fulfill their potential.

Providential, indeed.

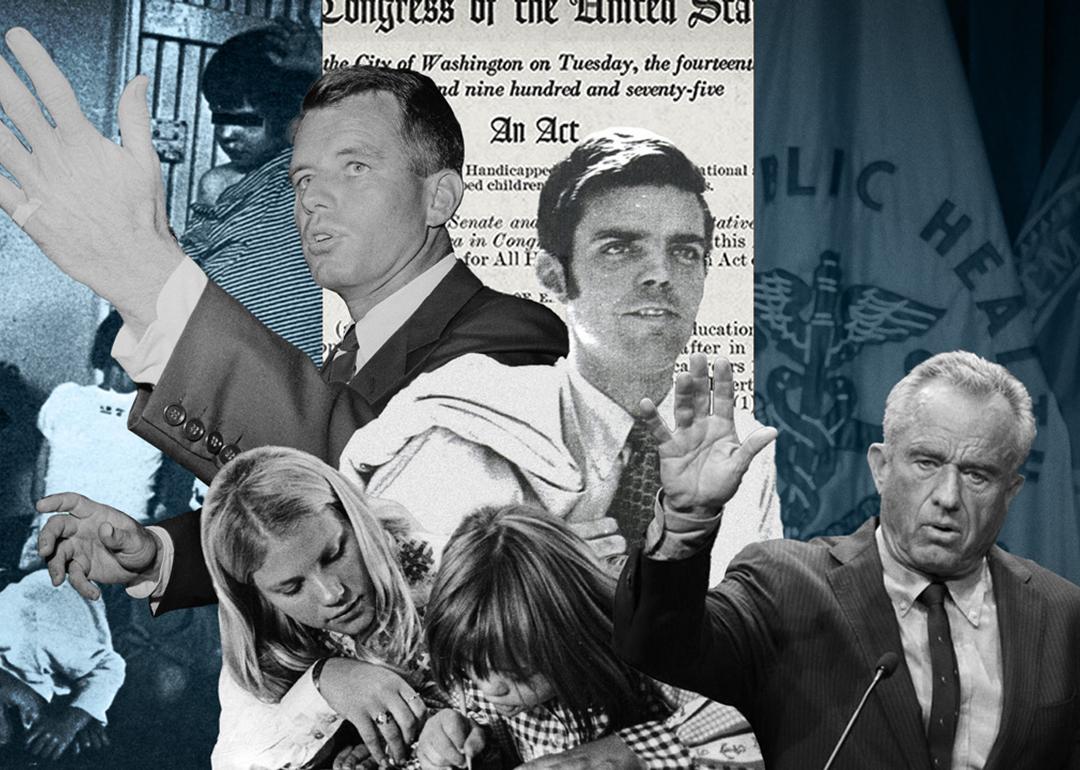

The cultural and political waters had been warmed up by a decade of Kennedy family activism. Rosemary Kennedy, sister to John F., Robert F. Sr. and Ted, had been born with a developmental delay, lobotomized as a young woman to a tragic result and institutionalized. JFK had to push for a new era for people with intellectual disabilities.

Indeed, upon in 1965, RFK Sr. . āWe have a situation that borders on a snake pit,ā he said. āThe children live in filth ā¦ many of our fellow citizens are suffering tremendously because of lack of attention, lack of imagination, lack of adequate manpower. There is very little future for these children who are in these institutions.ā

The Arc, the Council for Exceptional Children and other organizations pushing for more humane conditions knew it was time ā and that the moment called for someone with an audacious vision.

āThey knew they needed a lawyer who was prepared to imagine with them, and dream,ā Gilhool, who died in 2020, recalled in a series of interviews that are preserved as an oral history at the University of California, Berkeleyās Bancroft Library. āAnd act on those dreams with them to kick over the traces and to restructure the world which had so thoroughly confined them.ā

The 1971 case Gilhool filed and won, PARC vs. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, was swiftly copied by disability advocates in dozens of states. The settlement ā which anticipated the sundry ways in which children like Bob Gilhool were excluded from school ā became the template for one of the strongest of the eraās civil rights laws, enacted by Congress in 1975.

Fifty years after the passage of what is now known as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, itās hard to overstate the lawās impact. Originally titled the Education for All Handicapped Children Act, but better known as Public Law 94-142, it said no child could be declared ineducable. Advocates celebrated the end of the school-to-asylum pipeline.

Today, however, people with disabilities see flashing warning lights. In the sweeping proposals advanced by President Donald Trump, they see the start of a new era of institutionalization. And in the dehumanizing descriptions of disabled children made by Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. ā who grew up visiting his aunt at her asylum ā they hear echoes of past rhetorical justifications. The same groups that tapped Gilhool half a century ago today are suing to protect the law.

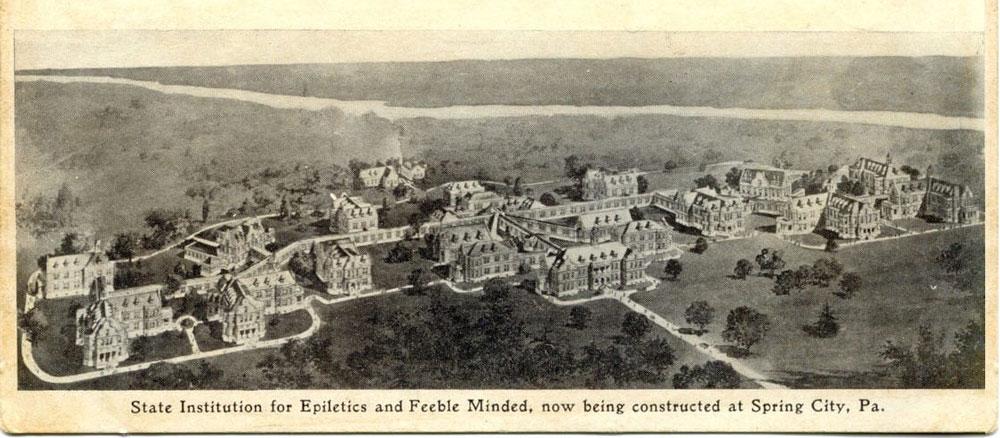

Pennhurst was not built to care for people who could not live independently. Like most asylums, the motive for its construction was crystal clear: eugenics.

The eraās dominant belief was that disability, poverty and race were matters of poor breeding. In the parlance of the time, ānormalā children needed protection from exposure to disordered ones. āIdiotic, imbecile or feeble-minded personsā should be , the Pennsylvania legislature proclaimed. State after state mandated confinement, and many went so far as to order the sterilization of anyone deemed defective.

Conditions at Pennhurst were wretched.

āLarge numbers of retarded persons have been herded together to live as animals in a barn, complete with stench,ā said the report that The Arc leaders gave to Gilhool. āMany are forced into slave labor conditions; deprived of privacy, affection, morality; suffering the indignities of nakedness, beatings, sexual assaults and exposure. Some are doped out of reality with chemical restraints while others are physically deformed by the mechanical ones. Many are sitting aimlessly without motivations, incentives, hopes or programs.ā

was hardly a secret. But without services to help care for their children or classrooms where they could learn, families struggled to stand up to authorities who pushed institutionalization, which is how Bob Gilhool ended up at Pennhurst.

The third child born to Tom and Mary Gilhool, Bob was social and curious. As a result, he was not diagnosed as intellectually disabled until it turned out he was also slow to talk and toilet train. For a little while, he went to a special school, but only for two hours at a time, twice a week. The rest of the time, he was home.

At the time, a childās developmental disabilities were viewed as the parentsā deficit. āThe diagnosis was very wrenching to my mother and father,ā Gilhool would tell the UC Berkeley oral historian. āThe learned understanding that it was, of course, the parentsā fault; that these things were genetic ā¦ and that they should be embarrassed and ashamed and feel guilty.ā

Gilhoolās father was taunted and shamed at work for having a disabled child, to the point that he had what was then called a nervous breakdown. Still, the family resisted expertsā recommendations to institutionalize Bob, who was 10. A few years later, dying of pancreatic cancer, the older Tom urged his wife to consider sending her youngest away.

āProbably, youād have to look around and find a place for Bobby,ā Gilhool recalled his father telling his mother one night. āBecause surely ā¦ you will not be able to keep him at home.ā

It was 1954, and Tom Gilhool was 13. Gilhool later recalled that as a child, he believed it was his job as an older brother to set aside his anger at what was happening and focus on keeping his motherās spirits up.

Whatever Bob understood, he did not complain.

During the nine months when attorney Tom Gilhool was exploring ways for The Arc to take on the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, he heard, over and over again, including via , about the role schools played in funneling children to Pennhurst.

Like Mary Gilhool, sometimes parents were simply unable to provide around-the-clock care unassisted. But often, families would enroll their children in school, only to have them rejected. Commitment, social workers and other experts would argue, wasnāt just in the best interest of the retarded children; it was to protect their siblings and spare their parents experiences like that of Gilhoolās father.

A Catch-22 for Parents

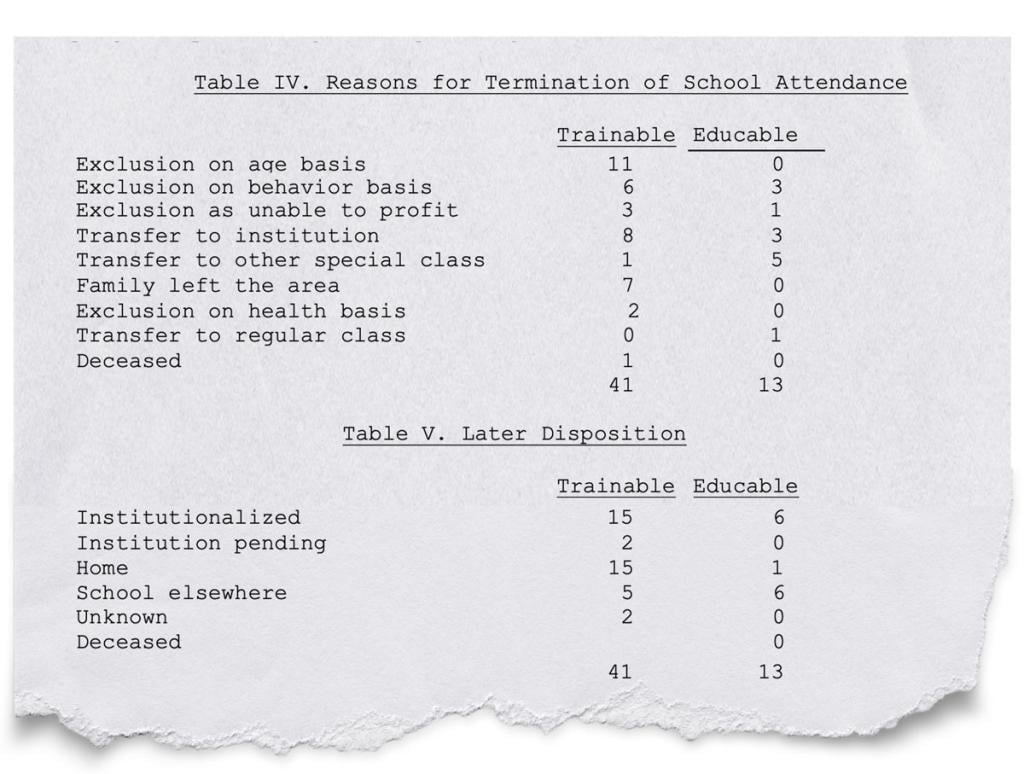

In 1955, around the time Bob Gilhool was being institutionalized, Minneapolis Public Schools opened an experimental school in a former orphanage and polio hospital. on The Sheltering Armsā first five years provides a vivid illustration of how school was frequently the first step toward confinement in an asylum.

Today, to guard against children languishing, IDEA requires schools to assess individual studentsā needs, identify strategies for meeting them and document progress, or lack thereof. But in 1960, Sheltering Armsā administrators were free to dismiss pupils they believed were neither āeducableā or ātrainableā for a variety of general and subjective reasons.

An outburst-prone 8-year-old, for instance, was dropped for being āunable to adjustā despite having gained six IQ points during his seven-week school trial period. āHis family situation was also a āproblemā one,ā evaluators wrote, so they called in county welfare officials to arrange āinstitutional placement.ā

Another 8-year-old was excluded for behaviors that included wanting āmaternal-style closenessā with his teacher. During his trial, he learned to āplay happilyā with other children and formed āsome meaningful social relationshipsā with adults. But in the evaluatorsā opinion, āThese gains seemed too small to justify the time and attention he was consuming in the classroom.ā

Though they were often vague when it came to documenting their own efforts, the Sheltering Arms evaluators were quick to scrutinize studentsā home lives in search of justifications for institutionalizing a child.

In administratorsā opinion, parents who said they faced minimal issues at home often were in denial: āTheir discrimination will also be affected by the degree of their defensiveness about the fact of the retardation,ā the program report explained. āA parent unable to accept this emotionally may very well proceed, in her diary, to deny all problems and describe the child as āperfectly alright.āā

Sometimes, children were excluded because evaluators felt the break their family got while they were in class only postponed a painful, inevitable decision. āThis was a situation in which we felt that school attendance was permitting the family to just barely survive the situation so that, in effect, a disservice rather than a service was being done to the whole family unit,ā Sheltering Arms reported in one case. āThese parents were highly realistic and competent people, and his exclusion from school led to institutional placement rather promptly.ā

The report declared the overall effort a success. Children gained independence, communication and socialization skills and behaved better. Still, it recommended institutionalization as the long-term outcome for most ātrainableā children, and parent education as key to achieving it.

āWe think that great harm is done by the casual provision of classroom experience for children with no effort to interpret to parents in what ways and for what reasons this experience differs from that which their normal children are having in school,ā they wrote. āWe see this kind of provision as a step backward.ā

Of the 54 children enrolled in the five-year experiment, 23 were subsequently confined to institutions in Minnesota, while 16 were sent home with no possibility of future education.

PARC v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania

On Jan. 7, 1971, Gilhool filed a federal against the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and 13 school districts with the backing of numerous advocacy groups, most notably the Council for Exceptional Children, the American Association on Mental Deficiency and the National Association for Retarded Citizens.

Gilhoolās goal was to get the court to outlaw the classification of any student as āineducable.ā To that end, the stories of the 13 children named as plaintiffs were representative of the array of excuses schools used to justify their exclusion.

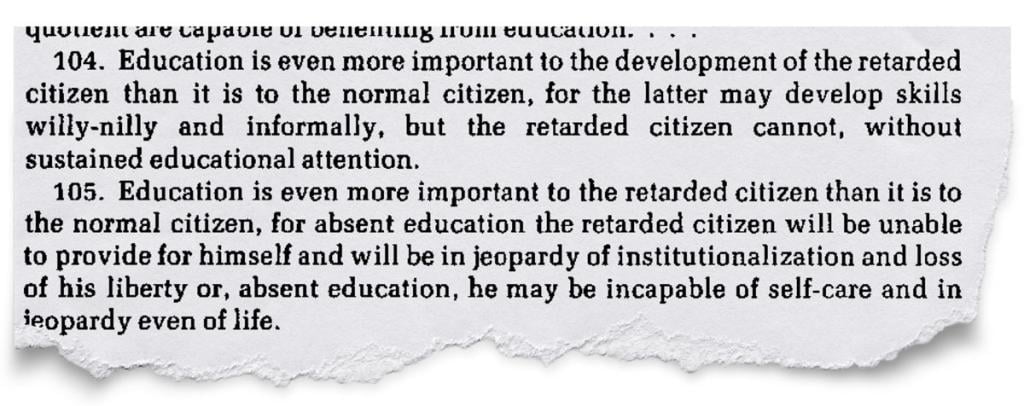

Citing Brown v Board, in 134 numbered paragraphs, that the stateās failure to educate all children violated the U.S. Constitutionās due process and equal protection clauses:

On Aug. 12, the court was scheduled to hear preliminary statements from seven witnesses. In the afternoon, after just four had testified, the three-judge panel hearing the case stopped the proceedings. Gilhool and his opposing counsel agreed to turn their efforts to drafting an order for the court to approve. On Oct. 7, the judges signed off on the document.

āThis landmark agreement commits the state to a program of identifying, locating, evaluating and placing of all children adjudged to be retarded,ā Gov. Milton J. Shapp said at a news conference the next day. āIn the long run, this agreement will save the taxpayers money because it is a known fact that many children adjudged to be retarded can lead normal and productive lives if given the proper kind of educational assistance early enough. In the short run, this agreement seeks to put as many children as feasible into the public school system.ā

The New York Times weighed in with an editorial: āThe court ruling is humane and socially sound. Whatever the cost of educating retarded children, the cost of setting them adrift in the world without giving them the means to lead useful lives is far higher.ā

The suit and settlement were quickly copied by advocates in 26 other federal court cases, pressuring Congress to act. In 1975, lawmakers passed what was then known as the Education for All Handicapped Children Act, guaranteeing the right to a free, appropriate public education for all students, including those with severe disabilities.

On Dec. 2, 1975, President Gerald Ford signed the bill, but reluctantly, noting both that Congress promised states more money than it actually appropriated and complaining, in essence, that Gilhoolās checks and balances ā the oversight required by the law to keep schools from shirking their obligations ā were burdensome.

āEveryone can agree with the objective stated in the title of this bill ā educating all handicapped children in our nation. The key question is whether the bill will really accomplish that objective,ā . āIt contains a vast array of detailed, complex and costly administrative requirements which would unnecessarily assert federal control over traditional state and local government functions.ā

Ford was right about the first part. Congress promised to fund 40% of IDEAās average per-pupil cost but has never appropriated anything close to full funding. Right now, states get 13%.

But as for the checks and balances, Gilhool was correct in anticipating that states and school districts ā historically poor enforcers of civil rights ā would need continuous federal oversight to deliver on the lawās central tenets: that children with disabilities have a right to a āfree and appropriate public educationā in the āleast restrictive environmentā possible.

Creating Special Education

By the time the PARC case went to trial, Brown v. Board of Education had been the law of the land for 17 years. Yet from coast to coast, communities had to return to court to try to force districts to take even baby steps toward integrating schools racially.

Anticipating similar resistance to desegregating students with disabilities, Gilhool asked the court to give the Pennsylvania defendants one year to find kids who were not being served by schools ā and to continue to identify children who might have unmet needs.

The clause became one of IDEAās most important provisions, a duty known as Child Find. It requires school systems to seek out and evaluate students who may need special education services ā no excuses. It applies to children from birth to age 21, whether they are being homeschooled or are enrolled in a private school, are migrants or are without homes.

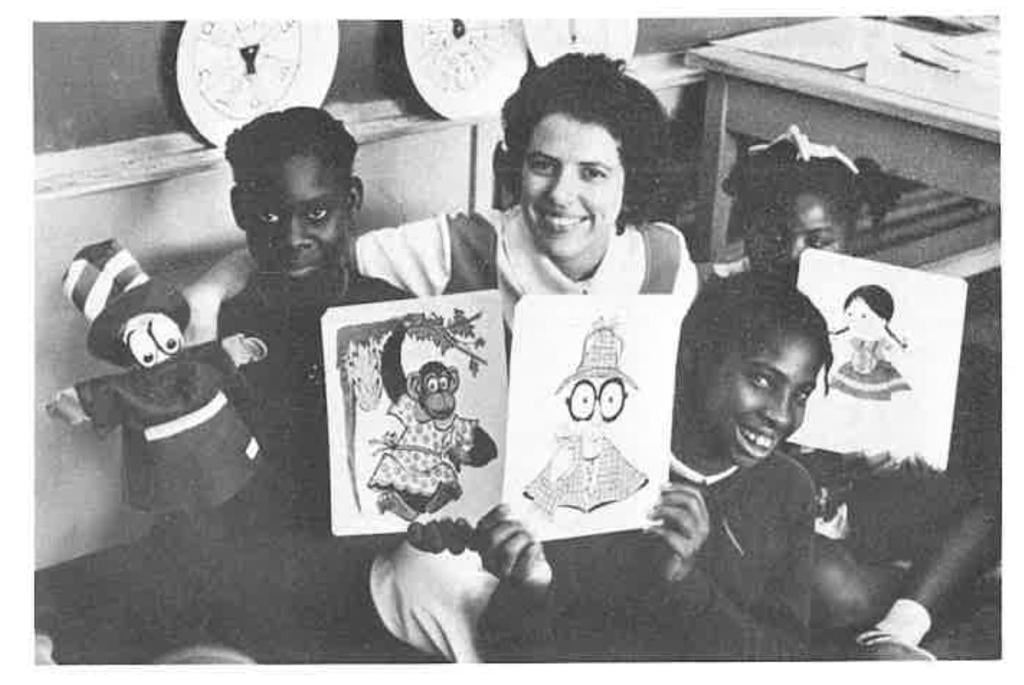

When IDEA became law, Linda Stevens, pictured below, was one of a very small number of educators trained to work with children with disabilities. A speech pathologist with a masterās degree ā rare for a woman at the time ā she taught a class of ā18 educable mentally retarded studentsā in Floridaās Alachua County Public Schools.

āSo much of retardation can be attributed to a language problem,ā she was quoted as saying in the April 1974 newsletter of the local chapter of the Council for Exceptional Children. āIf you can get the students to master the oral skills first, the difficulty of other tasks is then reduced.ā

To that end, her class played phonics-heavy games with puppets and enjoyed homemade books on tape. Stevensā efforts were so admired that the University of Florida sent special education teaching candidates to learn in her classroom.

When the federal law passed, Stevens and an art-teacher neighbor were tasked with figuring out how to fulfill the districtās Child Find obligations, according to her daughter, Elizabeth Clark, now a teacher in the same school system and a member of the Council for Exceptional Children. Working together, Stevens and her neighbor canvassed the community, showing up at doctorsā offices, PTA meetings and other places families congregated.

āAt the dinner table, my mother would talk about having spent the day going door to door ā¦ to let families know that their kids with exceptionalities, moderate to severe, were not only now allowed to come to school, but would have supports,ā says Clark.

The shame of having a child with an intellectual disability that had visited the Gilhools was still prevalent, so the women had to do a lot of coaxing. If a family wouldnāt agree to a home visit, Stevens would invite them for coffee. After each conversation, she would ask whom else she should reach out to.

The hardest part of the job was persuading people that schools would heed the law instead of finding justifications to exclude their children. āSometimes she would have to visit with a family three times to convince them,ā says Clark. āPeople were in disbelief.ā

Once, a parent got up mid-sentence and called a relative: āThereās a lady here that says so-and-so can go to school even though he canāt use the toilet by himself,ā the father said. āAnd that heās going to be okay.ā

At the same time, in Illinois, Pam Gillet was using every conduit she could think of to find families with children who were not in school. She placed announcements in newspapers and tacked handwritten notes on grocery store bulletin boards.

A member of the Council for Exceptional Children, Gillet, too, talked to parents who were reluctant to tell a stranger they had a disabled child, but also many who had tried to register their kids for school, only to be turned away.

āNow we were going back to those parents trying to build trust with them to say, āNow weāre going to welcome you,āā she recalls. āWe capitalized on the legal mandate that the parent must be an equal partner in the planning process and must agree to what the school district was recommending.ā

Unlike before, a district could not say it lacked the resources to meet individual studentsā needs. If a service was included in the Individualized Education Program, or IEP, that parents and teachers agreed to, the school must find a way to provide it.

Just as Gilhool had hoped, Child Find put bottom-up pressure on the entire school system to find the classrooms, research the strategies and recruit and train the staff to be able to offer meaningful opportunities. Even as they were trying to find their sea legs, educators like Stevens and Gillet got pressed into service to envision and build out entire programs.

Of the 33 fourth graders Gillet taught in 1968, her first year in the classroom, five had the word-recognition skills expected of first graders, while another five had some ability to read but not to comprehend. Often, kids who were behind academically were funneled into vocational programs in eighth grade, so there wasnāt much fuss when students were allowed to languish.

Gillet turned to her principal for help, but didnāt get much. The school had an after-school program, but it was an informal effort, organized by concerned teachers, working without pay. Often, they grouped children according to where each was academically and assigned them to an educator who was strong in that subject.

Frustrated, Gillet enrolled in a new university program that promised to train teachers to work with children with disabilities: āI thought, āWell, even if I donāt get a masterās in special education ā because I wasnāt even sure what all that was ā Iād at least maybe get some help with the children I was going to have for the rest of the year.āā

Fast-forward six years to IDEAās passage, and Gillet found herself running a federally funded initiative to train general educators to teach special ed. Using empty classrooms in a school in the northwest part of Cook County, near Chicago, the program enrolled 20 to 25 teachers per term for two semesters.

During the first term, they would take intensive classes with instructors from five area universities. For the second, the teachers would work alongside highly qualified special educators. The goal was two-fold: to be able to staff special ed classrooms quickly and to expose faculty from different teacher preparation programs to colleagues with expertise in a variety of areas.

Federal officials were watching. Every three years, the Office of Special Education Programs ā a division Congress created to provide expertise and monitor IDEAās implementation ā would visit every school in the district. Still trying to figure out how to get the right staff in the right places to meet studentsā varied needs, Gillet valued the feedback from the visits.

As newly trained special educators opened classrooms throughout Illinois ā rising to the challenge of educating children whom schools had never before attempted to accommodate ā she sat back and considered how much had been built, and how quickly. āAll of those evenings and weekends that we all spent together, and all of the tough times that we said, āWeāll never be able to do this,ā we did it,ā she recalls thinking. āKids are in school, theyāre learning. Theyāre having opportunities that some never had and may not have had if it had not been for this law.ā

Ignoring the Experts

The doctor who diagnosed Brianne Burger as deaf at age 2 warned her parents that she was unlikely to graduate from high school. They ignored him, becoming zealous advocates out of necessity.

About 1 million U.S. children under 18 are blind, have limited vision, are deaf, hard of hearing or deaf-blind. Laws requiring publicly funded programs to educate them date, in one case, to the 1800s. Services are expensive, however, and states are quick to target them for cuts when budgets run lean. Because of this, the money, oversight and technical expertise required to keep them running are laid out in IDEA.

Burger is living proof both of statesā tendency to try to restrict access to costly programs and of disabled childrenās academic and career potential. When she was diagnosed in the early 1980s, her family lived in Stamford, Connecticut, 90 minutesā drive from the stateās only school for deaf children ā and the only option state officials offered.

Burgerās parents, however, were unwilling to put a toddler on a bus for three hours a day. By word of mouth, they learned of two schools for the deaf in New York. One was just 15 minutes from their home. Connecticut had to pay the New York tuition.

Burger got an excellent education there. When her family moved to Massachusetts, long a disability-friendly state, she was placed in a general-education classroom where her parents advocated for her to have an interpreter.

She ended up at a California university with strong services for deaf students, and later at Emerson College for graduate school. After a stint in vocational rehabilitation, helping people with disabilities find and settle into jobs, she went to work managing federal grants for Gallaudet University in Washington, D.C.

Her timing could not have been better. President Barack Obama had pledged to increase the number of people with disabilities employed by the government. Burger worked in disability policy for several federal agencies, landing at the U.S. Department of Education in 2016.

For nine years, she monitored a number of congressionally mandated institutions that provide expertise or services states donāt have: the American Printing House for the Blind; the Laurent Clerc National Deaf Education Center; Gallaudet University; the Helen Keller National Center for the DeafBlind; and the National Technical Institute for the Deaf.

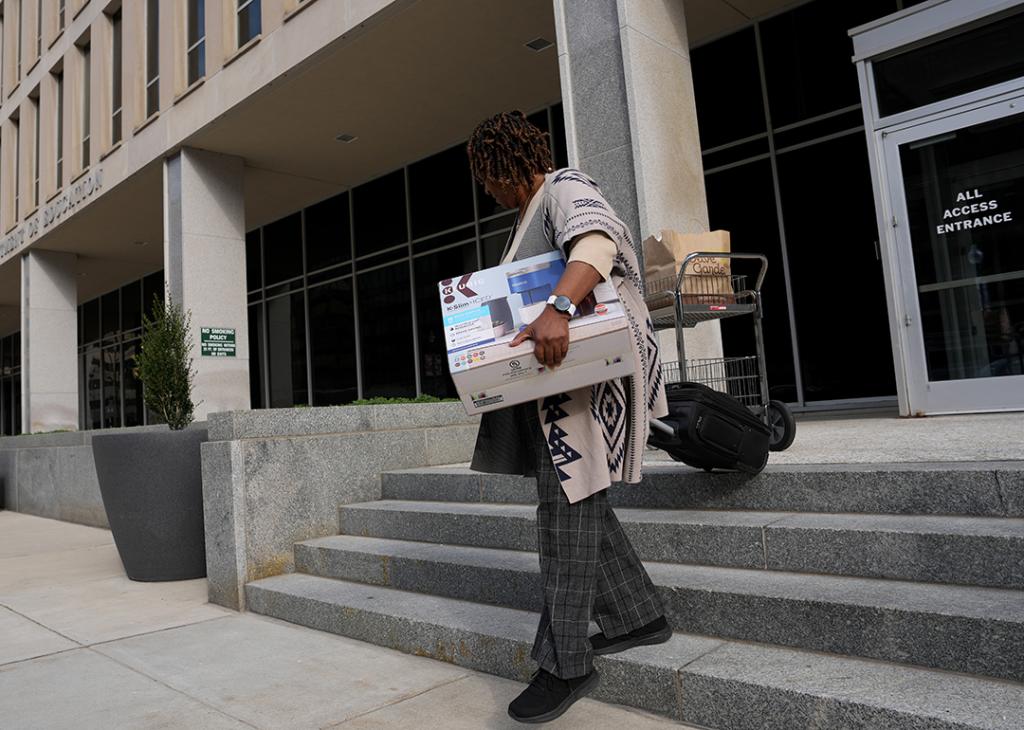

In March, despite the fact that the law requires her position to be filled, Burger was one of more than 1,300 Education Department employees fired as Trump attempted to close it. Since his second inauguration, millions of dollars in funding for at least a dozen programs to support deaf and blind students have been eliminated.

Shortly after Burgerās firing, South Dakota Republican Sen. Mike Rounds introduced legislation to transfer the departmentās responsibilities to other federal agencies. Under the bill, oversight and support for the organizations she oversaw would be assigned to the Department of Health and Human Services and the U.S. Department of Labor.

During the Great Recession of the late 2000s, Rounds ā then governor of South Dakota ā attempted to close the stateās residential school for the deaf, which was established in 1880. Federal stimulus funds saved it, albeit in a drastically curtailed form.

A task force appointed by Rounds recommended that its functions be assigned to individual districts, which can draw on the school for support. But without the pressure to staff a residential school, services have ebbed. In 2016, for example, the last university degree program for deaf educators closed, choking off the supply of interpreters able to work in regular schools.

This year, schools that serve deaf and blind students and universities that train their educators have been or threatened with closure in . At the same time, offices like Burgerās ā created to ensure states and districts donāt shirk their obligations ā have been hollowed out.

In March, a group of educators, school districts and public-sector unions , hoping to stop the Education Departmentās dismantling and reverse the mass firings. (The Arc of the United States has since joined the suit.) A Massachusetts judge issued an order halting the administrationās efforts, pending further legal proceedings, but in July, the U.S. Supreme Court reversed that ruling, at least temporarily allowing the dismantling of the department to proceed.

Education Secretary Linda McMahon has since laid off more of the departmentās employees, although some have been temporarily rehired.

If Trump and McMahon eventually succeed, the departmentās Office of Civil Rights, which investigates violations of disabled studentsā rights, will have shrunk from 446 employees to 62. The Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services ā one of the divisions Congress explicitly required in IDEA ā will retain just 14 of its 135 employees.

Echoes of a Dark Past

Over the last year, disability advocates have repeatedly warned that the Trump administrationās policies ā and the presidentās use of the slur āretardedā ā open the door to a return to the dark past. Most visibly, as health and human services secretary, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has repeated false claims about the causes of autism and promoted

āThese are kids who will never pay taxes, theyāll never hold a job, theyāll never play baseball, theyāll never write a poem, theyāll never go out on a date,ā he said in April about autistic children. āMany of them will never use a toilet unassisted.ā

Indeed, one of was to eliminate the Administration for Community Living, the HHS division that oversees programs that help people with disabilities and older populations be as independent as possible. The officeās responsibilities, he announced in March, will be handled by other parts of the agency.

Perhaps ignorant that Pennhurst and other asylums forced residents to grow their own food, Kennedy has also proposed the creation of āwork farms,ā where hard labor will supposedly heal people struggling with addiction, mental health issues and even attention deficit disorder.

In July, Trump opened the door to reinstitutionalization with an executive order titled āEnding Crime and Disorder on Americaās Streets.ā It calls for āthe reversal of federal or state judicial precedents and the termination of consent decreesā that limit broad institutionalization, threatening to withhold federal funds from states and municipalities that donāt adopt and enforce āmaximally flexibleā commitment standards.

Like the laws that justified confining in asylums people perceived as dangerous, the edict proposes to ārestore public orderā via the ācivil commitment of individuals with mental illness who pose risks to themselves or the public or are living on the streets and cannot care for themselves in appropriate facilities for appropriate periods of time.ā

A statement from the American Bar Association raises Gilhool used to frame PARC: āThe order raises serious constitutional and civil rights concerns ā particularly regarding due process under the Fourteenth Amendment and the rights of individuals with disabilities under the Americans with Disabilities Act. Its proposed standard for commitment ā encompassing not only those who pose a risk to self or others but also those who are merely unable to care for themselves ā falls short of established constitutional safeguards.ā

Hoping ā,ā in 2010 a group of advocates and former residents formed the Pennhurst Memorial and Preservation Alliance with the intent of acquiring the abandoned facility and turning it into a national museum of disability history.

But a businessman by the name of Robert Chakejian beat them to it, paying the state of Pennsylvania $2 million for Pennhurst in 2008. Chakejian was struggling to turn a profit on a composting business he had started on the grounds when his teenager suggested he convert the asylum ā and its abandoned cribs, beds, wheelchairs and an electric shock chair ā into a haunted house.

After they sued and lost, advocates tried to persuade the entrepreneur to at least populate the attraction with vampires and monsters instead of mental patients. But when the haunted house opened in September 2010, it had an asylum theme, complete with a fictional backstory involving a made-up Austrian scientist (named Dr. Chakajian, an intentional misspelling of the ownerās name) who experimented on Pennhurstās prisoners.

These days, thereās a ā complete with actors in gory makeup who lunge at visitors ā and holiday events like āCrazy Christmasā and āBloody Valentine.ā Because itās too scary, children and pregnant women are not allowed to tour. Active members of the military get discounted admission.

Between 1908 ā when Pennsylvania built what was originally called the Eastern State Institution for the Feeble Minded and Epileptic ā and 1987, nearly 11,000 people were confined to Pennhurst. About half died there, historians estimate.

After Pennhurstās closure, some 150,000 people moved out of institutions nationwide. Since then, an estimated half a million have been spared institutionalization.

In one of the longest-running to date, researchers at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and Temple University stayed in touch with 1,156 people who were at Pennhurst in 1978. Each got a visit once a year, aimed at answering a single question: āAre the people better off than they were at Pennhurst?ā

They were. None wound up homeless or in jail. They lived an average of six years longer than those confined had, and their care cost 15% less than in the institution. Many moved into small group homes in the community.

Bob Gilhool was among those who eventually lived independently. Long after the trial that began the process of emptying the asylum, Tom Gilhool asked whether his brother wanted to tag along on a visit the lawyer was making with a group of Japanese disability activists.

No way, was the quick response Tom Gilhool told an interviewer compiling for Temple Universityās Institute on Disabilities. But he was proud.

āAs Bob tells me often,ā Gilhool said, beaming, āāYou and I closed Pennhurst.āā

was produced by and reviewed and distributed by Ā鶹Ō““.