In Arizona, a fight against a deadly fungus is under threat from TrumpŌĆÖs health policies

In Arizona, a fight against a deadly fungus is under threat from TrumpŌĆÖs health policies

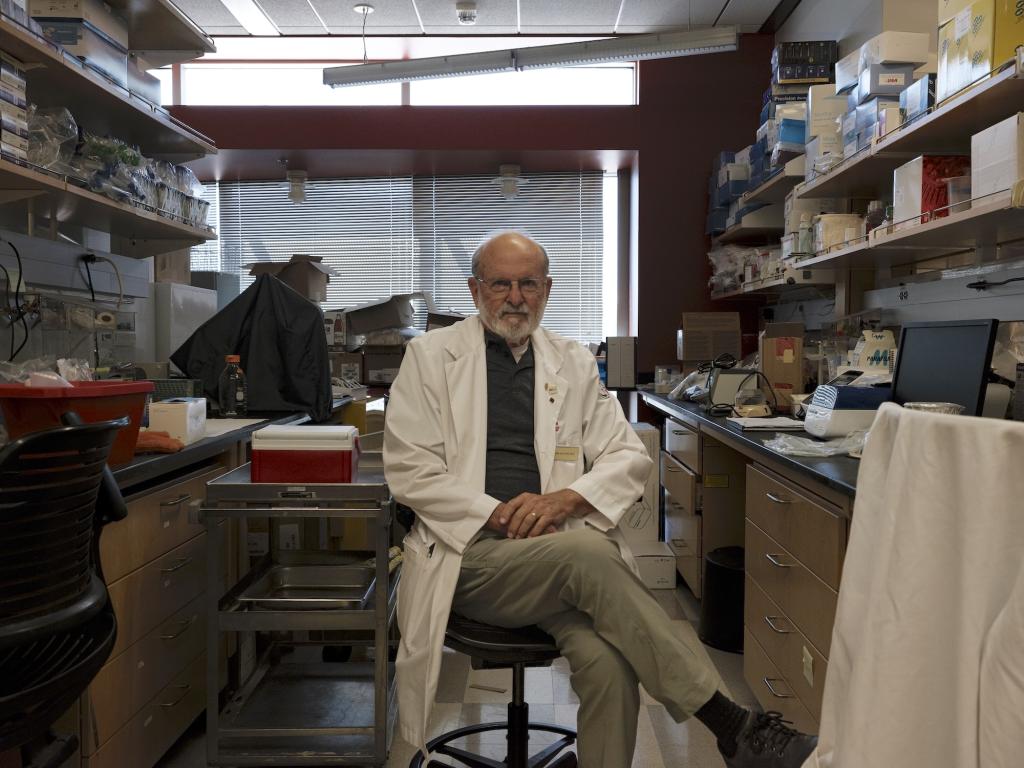

The 79-year-old physician is sitting on a chair in a side office at a health clinic in Phoenix, Arizona, long legs crammed under the table in front of him, hands folded at his stomach, when his cell phone rings. ŌĆ£ThereŌĆÖs my guy,ŌĆØ he says.

The man on the other end, a physician who works in Tucson, is a touch less relaxed. One of his patients has been in and out of the hospital with a respiratory infection so severe that at one point she coughed up blood. Her skin is flaking, sheŌĆÖs losing her hair, and now the ventricles in her heart are taking too long to refill with blood between beats. The physician suspects some of these symptoms are being caused not by her underlying condition, but by the medication he has her on. The problem is, her insurance is refusing to cover a more expensive alternative.

Dr. John Galgiani (below), the countryŌĆÖs leading expert on the disease in question, quickly cuts him off. Take the patient off the medication, he says, and see how she does. If she improves, show the insurance company proof and force its hand. ŌĆ£ThatŌĆÖs actually a good idea,ŌĆØ the doctor replies.

The conversation is so routine, its conclusion ŌĆö a change of medication ŌĆö so anodyne, itŌĆÖs easy to forget that the patient theyŌĆÖre talking about is battling a deadly and incurable fungus.

Doctors have been searching for a cure for coccidioidomycosis, the disease afflicting the patient, since the 1890s, when an Argentine soldier was hospitalized with skin lesions that returned with a zombie-like vengeance after being scrubbed or cut off, reports. Not long after, an immigrant farmworker landed in a San Francisco hospital with the same mutilating disease. Both patients eventually died.

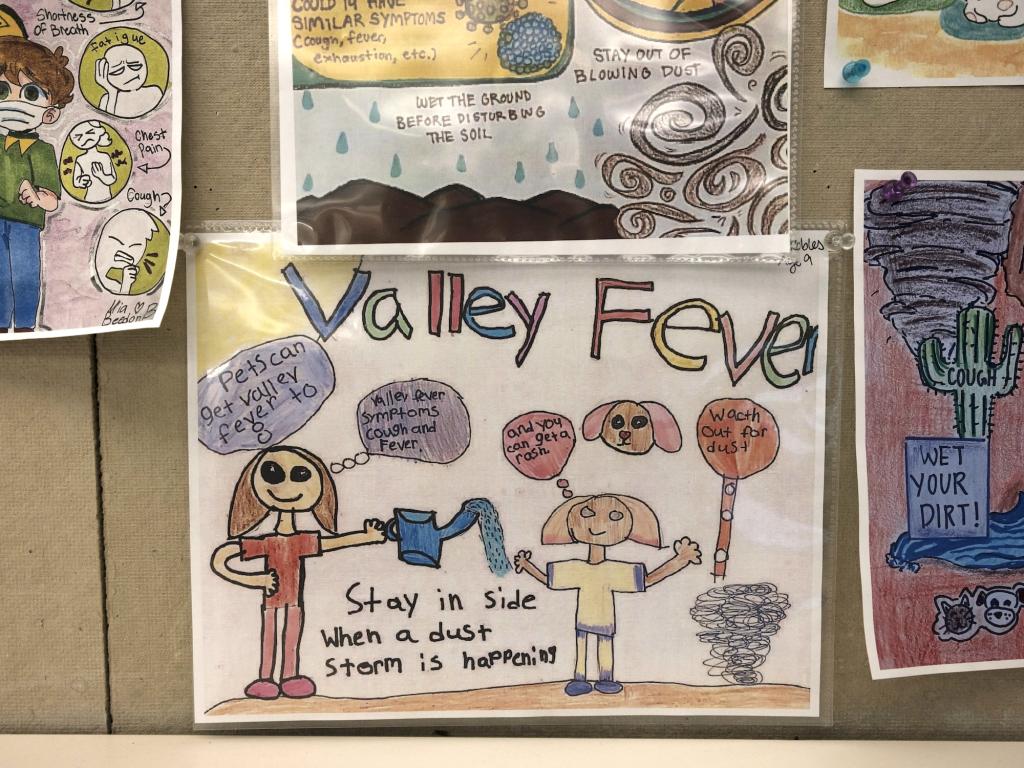

It would be decades before medical researchers and public health officials connected the dots between those cases and reports of a mysterious disease referred to simply as ŌĆ£ŌĆØ by the waves of settlers, immigrants, and farmworkers that rippled through the West on the heels of the Gold Rush, the completion of the transcontinental railroad, and the Dust Bowl. In CaliforniaŌĆÖs San Joaquin Valley, the disease was known as ŌĆ£San Joaquin Valley Fever,ŌĆØ and ŌĆ£valley feverŌĆØ became the colloquial name of the infection Galgiani later dedicated his life to studying.

By the 1930s, scientists understood that valley fever and the disease that killed the two immigrant farmworkers were different stages of one illness caused by the same fungal pathogen. They had also begun to grasp the basics of transmission. The fungus that causes the disease, called coccidioides or cocci (pronounced ŌĆ£cox-eeŌĆØ) for short, grows in the top few inches of undisturbed earth throughout the Western U.S. and flourishes during cool, rainy periods. Then, in the summertime heat of the desert, its delicate fungal threads desiccate. Once theyŌĆÖre dry, any disturbance of the topsoil ŌĆö a foot kicking up earth, a bulldozer digging a foundation, an earthquake shaking loose clouds of dust ŌĆö sends infinitesimal spores swirling into the air, where they can be sucked through the nasal passages and into the lungs of passing humans or animals.

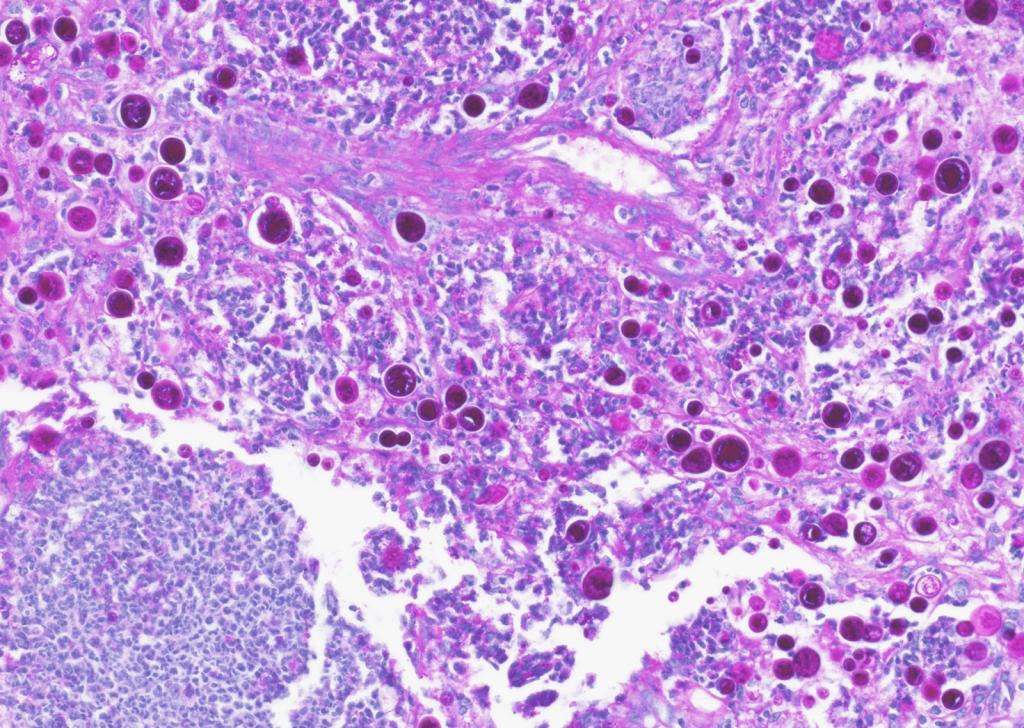

Most people who breathe in cocci spores ŌĆö about six in 10 ŌĆö wonŌĆÖt develop symptoms. But the 40% of exposed people whose immune systems canŌĆÖt or wonŌĆÖt fight off the fungus develop symptoms such as fatigue, muscle aches, coughing, and rash that can last weeks or months. In the 5 -10% of symptomatic cases where the fungus invades the vital organs, the death rate is as high as . The pathogen is so powerful that the U.S. army in the 1960s. (A histological slide of valley fever spores in the lung tissue of a dog is shown below.)

Valley fever is endemic to southern Washington, Oregon, California, Nevada, Utah, New Mexico, Texas, and parts of Central and South America, but nowhere are cases of the disease more common than in Arizona. After Arizona started mandatory laboratory reporting for valley fever in 1997, registered cases ticked up and down. But the number began trending upward dramatically in 2016. Then, in 2024, cases in the state exploded, hitting . were reported ŌĆö a 37% increase over 2023. California, which runs just behind Arizona in its annual valley fever caseload, registered a , representing a 39% increase over the previous year, which had already smashed a record set in 2019.

Some portion of the rise in reported cases represents growing awareness among physicians and an associated surge in testing. The pace of new construction in untouched areas also plays a role.

But the recent increase in cases has been so dramatic, Galgiani and other researchers across the West who study the fungus think another factor may be driving the trend: supersoaker winter monsoons followed by scorching summer heat and drought, a cycle made more intense by climate change.

Because warmer air holds more moisture, monsoons and other major rainfall events pull in larger quantities of water vapor and produce heavier downpours as the planet warms. This physical fact has fueled a spate of across the U.S. and around the world in recent years. But the same warmth can conversely lead to drought by making the or capable of absorbing more water from the landŌĆÖs surface. Both conditions ŌĆö the wetter conditions by encouraging growth of the spores, and the drier conditions by facilitating desiccation and soil disturbance.

ŌĆ£The main driver for us is certainly this very clear association for coccidioides between heavy precipitation cycles followed by drought,ŌĆØ said George Thompson, a professor of medicine at the University of California, Davis, School of Medicine who specializes in fungal diseases.

And itŌĆÖs not just valley fever that may increase its spread thanks to climate change. Peer-reviewed research shows that are in a warming world.

Since many valley fever cases are asymptomatic or diagnosed as something else, the numbers of infected people reported by states every year are widely considered underestimates. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says that the true burden of valley fever in the U.S. is , meaning tens or hundreds of thousands of people in Arizona and California have been touched by these latest spikes. Cases reported so far this year are surging in .

This is the kind of challenge Galgiani has spent the better part of three decades preparing for. Since 1996, Galgiani has served as director of a Tucson-based center he founded at the University of Arizona called the Valley Fever Center for Excellence, where a small army of researchers, doctors, and veterinarians works closely with county and state public health agencies and research universities on developing solutions to the stateŌĆÖs multifaceted valley fever problem. Years of dogged work are finally beginning to yield momentum that could prevent thousands of infections and dozens of deaths every year.

What might become the worldŌĆÖs first-ever fungal vaccine, discovered by Galgiani and a team of researchers at the Center for Excellence in 2013, is nearing the end of the long federal regulatory process for use against valley fever in dogs. A pharmaceutical company has already initiated the process of adapting it for use in humans.

Galgiani and his colleagues also teamed up with researchers at Arizona State University to that uses data from National Weather Service weather stations to track the environmental conditions that spur cases of the disease. He designed a clinical education program that trains physicians how to more quickly and accurately diagnose valley fever in their patients. The program was owned by Banner Health, one of the biggest nonprofit healthcare systems in the U.S.

But these efforts, some of the first homegrown examples of researchers and health professionals collaborating to protect their communities against a climate-driven health threat in the U.S., are on a collision course with the Trump administrationŌĆÖs new policies. In the months since Donald Trump was elected president, his administration has systematically undermined the infrastructure that supports the countryŌĆÖs public health systems, ordering to , , and , and even on new cases of infectious disease.

For decades, Galgiani thought the work he was doing at the Valley Fever Center for Excellence was building a solid foundation that Arizona would be able to depend on in the hotter years to come. The first nine months of the second Trump administration have made that foundation look more like a Jenga tower. The infrastructure supporting everyone Galgiani works with ŌĆö the research to develop a vaccine that may one day become widely available for human use, the valley fever surveillance tools that rely on government weather data to operate, and the federal funding that pays for ArizonaŌĆÖs public health initiatives, public universities, and research labs ŌĆö is starting to wobble.

The quest to free Arizona of its fungal scourge, never closer to bearing fruit, has also never been more at risk.

As Sharon Filip, a healthy woman in her 50s, was preparing to depart Washington state for a two-week vacation in Arizona in 2001, she checked the stateŌĆÖs Department of Health website to find out what she should be aware of before her trip. As a result, she arrived in Tucson prepared to avoid scorpions at all costs. Nothing she read indicated that a deadly fungal disease lurked in the soil.

A week after returning home, Filip could barely lift her head off her pillow. ŌĆ£Every bone in my body, every muscle in my body, every part of my body, my organs ŌĆö everything hurt,ŌĆØ she said. Her doctors had no idea what was wrong.

FilipŌĆÖs son, David, took care of her, and her illness resolved on its own over the course of months, as many cases do. There is no cure for the disease, though a round of strong antifungals, which come with their own suite of painful side effects, can provide the immune system with an assist as it tries to destroy the spores. Filip said it took her 10 years to fully ŌĆ£come back to the world of the living.ŌĆØ She and her son formed a group called Valley Fever Survivor, which has served as a meeting place of sorts for people desperate for more information and guidance.

Arizona has accounted for at least two-thirds of all cases reported in the U.S. for decades, although California is beginning to reach parity as the fungus spreads. Maricopa County in particular ŌĆö ArizonaŌĆÖs most populous and diverse county, housing four of the five biggest cities in the state, including Phoenix ŌĆö is located on what appears to be a massive fungal reservoir. Half of all of the nationŌĆÖs cases . But even in Maricopa County, getting an accurate valley fever diagnosis often depends on whether either the patient or the doctor is aware that such a disease exists.

ŌĆ£I went to a hospital four different times between three different locations before I was taken seriously,ŌĆØ someone wrote in a valley fever support group on Facebook recently. ŌĆ£As a native to Arizona who has only heard of valley fever and does not know anyone who has had this, I find it all incredibly shocking.ŌĆØ

Unlike nearby California, Arizona has passed no workersŌĆÖ protection legislation aimed at controlling one of its most commonly reported infectious diseases. The state legislature, controlled almost exclusively by a Republican majority , approved just $300,000 for valley fever surveillance . No new funding has been approved by the legislature since, though the Arizona Board of Regents, the state senate-confirmed board that governs ArizonaŌĆÖs university system, to fund valley fever research across six projects starting in 2022.

Sharon and David Filip are scathing about ArizonaŌĆÖs efforts to contain the disease, which have largely amounted to improving detection of valley fever in people who already have it, rather than preventing those infections from happening in the first place. They think the state has that backward.

ŌĆ£It seems like itŌĆÖs more important to actually fund the protection of the people than it is to just keep track of how theyŌĆÖre dying and getting sick,ŌĆØ David Filip said. But preventing cases of valley fever ŌĆö a disease that people contract simply by breathing in the wrong place at the wrong time ŌĆö is a monumental job for a public health department.

When asked what Arizona is doing to combat valley fever, Irene Ruberto, who manages the Arizona Department of Health ServicesŌĆÖ vector-borne and zoonotic disease team, pointed to the departmentŌĆÖs efforts to raise awareness about the disease, such as the week the state dedicates to ŌĆ£Valley Fever AwarenessŌĆØ every November, as well as its ongoing work reviewing, counting, and publishing cases reported by counties. Ruberto had no firm answers to questions about the ways that new construction is exposing more residents to the fungus, and what else might be done to reach the demographics most at risk of developing the most severe form of the disease, nodding instead to research being conducted by scientists on those topics at places like the Valley Fever Center for Excellence, which the department supports.

ŌĆ£We donŌĆÖt want to scare people,ŌĆØ Ruberto said. ŌĆ£We want people to be aware, because weŌĆÖre seeing that if you know about valley fever, you know the signs and symptoms, then itŌĆÖs more likely that youŌĆÖre going to get tested.ŌĆØ

The department of health has a small pot of funding thatŌĆÖs already stretched thin between competing priorities. Arizona, which spent in 2023, less than half the national average, uses very little of its own money on its health infrastructure. If federal funding were to disappear ŌĆö county health departments are funded largely by Medicaid ŌĆö the stateŌĆÖs public health system would .

ŌĆ£ThereŌĆÖs a fungus amongus,ŌĆØ reads a small decal tucked among the various framed awards and pictures hanging on the walls of his office at the Valley Fever Center for Excellence. Galgiani spends most of the week in Tucson, but on Tuesday nights, he and his wife drive two hours north to Phoenix to an apartment they own on the bottom floor of a building, a five-minute drive from one of Banner HealthŌĆÖs clinics. On Wednesday mornings, Galgiani goes to the clinic to see patients and train doctors.

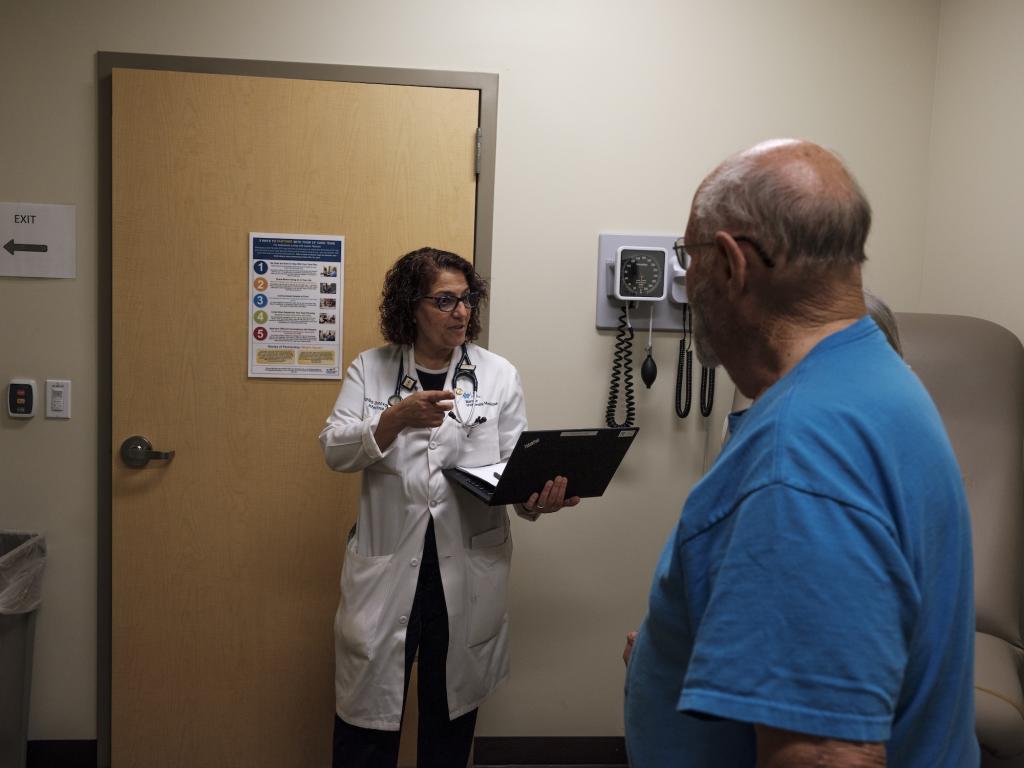

Since 2018, Banner Health urgent care facilities in Phoenix and Tucson have been following a Galgiani designed which aims to increase the number of people being tested for valley fever. Too often, doctors assume that patients who present with the early symptoms of valley fever have garden-variety pneumonia, and they administer antibiotics without realizing that the patient is suffering from a fungal infection that will only respond to an antifungal medication.

A of more than 800 patients in Arizona found that more than 40 percent of them waited more than a month after their first doctorŌĆÖs visit for an accurate diagnosis; many received useless prescriptions for antibacterial drugs in the interim. The costs associated with the roughly 10,000 cases of the disease that were diagnosed in the state in 2019, including direct healthcare costs and working hours lost, .

After GalgianiŌĆÖs protocol was implemented, the percentage of Banner Health clinics enrolled in the program ordering 50 or more valley fever blood tests per year rose significantly, ŌĆö a strong signal of progress and one that will likely withstand any changes unfolding at the federal level: The program is cheap and doesnŌĆÖt rely on federal funding to run. But the Banner Health facilities using this new strategy constitute just 4% of the health clinics in the Phoenix and Tucson metropolitan areas. The long-term goal, which the state of California is currently trying to accomplish , is to require doctors to automatically test most patients who present with pneumonia symptoms in an endemic area for the disease.

But getting more hospitals and clinics across the southern part of Arizona, which encompasses most of the stateŌĆÖs fungal hotspots, to implement updated valley fever testing protocols is a constant battle against inertia. ŌĆ£A lot of doctors have learned to treat all pneumonias as bacterial infections,ŌĆØ Galgiani said. ŌĆ£To get them to change, they have to unlearn what they were already told was the right way to go.ŌĆØ He fears that, as the federal government takes a hatchet to the funding it sends to states for a wide array of public health initiatives, the momentum he and others in Arizona have been trying to sustain will lag and efforts to combat valley fever will fall to the wayside.

In late March, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., head of the Department of Health and Human Services, or HHS, for states across the country. Although ArizonaŌĆÖs attorney general alongside 19 other state attorneys general, the in August permitting the lionŌĆÖs share of those cuts to go through. The White HouseŌĆÖs proposed budget for fiscal year 2026 would further weaken the stateŌĆÖs public health and research infrastructure: Arizona stands to lose an estimated $135 million annually in funding from the National Institutes of Health, or NIH, for infectious disease research at universities and hospitals, according to an analysis by the .

These cuts wonŌĆÖt affect the Valley Fever Center for Excellence, which is funded primarily by philanthropic dollars and was established by the Arizona Board of Regents, not the federal government. But whatŌĆÖs happening at the federal level is destabilizing the network of people and institutions Galgiani relies on to keep the valley fever solutions machine running, including the public health departments he works with and his collaborators at universities in California, Arizona, and Texas.

ŌĆ£It feels like thereŌĆÖs an ax hanging over our heads and we never know when itŌĆÖs going to drop,ŌĆØ said Bridget Barker, a professor of biological sciences at Northern Arizona University who runs a valley fever project funded by NIH.

For eight months this year, Barker waited for more than $1 million in grant money the federal government had already agreed to give her so she could continue developing new antifungal medications to treat valley fever ŌĆö funding that in past years has been approved in a matter of weeks. Barker wasnŌĆÖt sure if the money was slow to come because so many federal employees had been fired or laid off since the beginning of TrumpŌĆÖs second term, or if it wasnŌĆÖt going to come at all. In August, she finally got her funding. By that time, she had already had to lay off two staffers at her lab.

When Thursday morning rolls around, Galgiani is back at his desk in Tucson logging onto a Zoom call with a group of people who meet monthly to discuss valley fever in Arizona. Thomas Williamson, a valley fever epidemiologist at the stateŌĆÖs department of health, starts the meeting with a roll call. Representatives from public health departments across the state ŌĆö Maricopa, Pinal, and Pima counties ŌĆö are there to report their monthly valley fever numbers to the group of roughly two dozen. An infectious disease specialist from the Mayo Clinic is listening in. Galgiani is prepared to present the most recent data from his work with Banner Health clinics.

Williamson ticks down his list of invitees. ŌĆ£How about the CDC?ŌĆØ he asks. A long silence follows. Someone jumps in and asks if the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention was told about the meeting.

ŌĆ£They were sent the updates and the meeting link,ŌĆØ Williamson replies. ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs up to them, really.ŌĆØ

ItŌĆÖs unclear if the federal governmentŌĆÖs absenteeism is a result of a lack of interest or whether it can be chalked up to disarray and lack of personnel. At least seven staffers and research fellows have left the CDCŌĆÖs Mycotic Diseases Branch ŌĆö including the branch chief, Tom Chiller ŌĆö a small division within the agency that maintains a fungal identification and testing lab and helps states with funding, disease surveillance, and public health communication surrounding fungal pathogens. Either way, Galgiani says later, the absence is unusual.

Also tuning into the Zoom call are Tanner Porter and Dave Engelthaler, two researchers who have been using air filters ŌĆö initially installed around the Phoenix metropolitan area following the violence of September 11, 2001, to sense a bioterrorism attack ŌĆö to measure the concentration of cocci in the air. ItŌĆÖs the first-ever effort to forecast where and when the spores are present across a metropolitan area.

Interest is intense among the meeting attendees as Porter and Engelthaler, who both work at a nonprofit medical research group called the Translational Genomics Research Institute, report that their preliminary findings indicate that airborne fungus is most concentrated close to new construction sites. The spores, they say, are present even on days when the wind isnŌĆÖt blowing and there is no visible dust in the air.

Phoenix and other endemic areas undergoing a lot of landscape changes are a bit like minefields. Construction in places where the fungus is present, particularly when soil moisture is low and wind is blowing, can produce invisible clouds of spores that hang suspended in the air within a 1.5-mile radius. Anyone who walks through them could be at risk. Larger construction sites can send the spores swirling even further afield.

The researchers are in the midst of training a machine-learning algorithm to identify disturbed land in real time and identify where infections are likely to occur. ItŌĆÖs the kind of research that could help the Maricopa County public health department put out warnings in high-risk areas and encourage people to wear N95 masks, which have been shown to of contracting the disease.

But the work Porter and Engelthaler are doing depends in part on dust storm records kept in a little-known database called the Storm Events Database. That database is run by the National Centers for Environmental Information, housed within the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, or NOAA, which also runs an that the researchers are pulling from to run their modeling. The Trump administration , which will have knock-on effects for any ongoing efforts to use federal weather data to predict where and when valley fever will emerge.

The biggest unknown in the stack of unknowns is the future of the vaccine Galgiani discovered several years ago ŌĆö the holy grail of the valley fever world. Without it, there is no long-term protection for Arizonans, Californians, and anyone else exposed to a disease poised to run amok as communities push further into a desert landscape made more hospitable to coccidioides by climate change.

The vaccine has been licensed to a pet healthcare pharmaceutical company called Anivive Lifesciences, which is developing it for use in dogs ŌĆö animals that are particularly susceptible to the disease because they spend so much time with their noses to the ground. The company counts former Republican Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy, who represented much of CaliforniaŌĆÖs cocci-rich Central Valley, on its board.

If everything goes exactly right, the vaccine Anivive is developing will be approved by the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, a branch of the United States Department of Agriculture, for use in canines by the middle of next year. In trials, two doses of the live attenuated vaccine, which contains a weakened form of the fungus, gave dogs near-total protection. Adapting the mechanism that makes the dose work in dogs to provide the same protection for humans could take another five years or more. But the federal government appears interested in making that happen ŌĆö or, at least, it did.

Last year, Anivive received a contract from a division of the National Institutes of Health to initiate the process for a human phase 1 clinical trial. Once someone has recovered from valley fever, theyŌĆÖre more or less protected from reinfection for life, making the fungus a good vaccine candidate. The funding from NIH is in the form of a legal contract, not a grant, meaning it theoretically canŌĆÖt be rescinded the same way have been cancelled by the federal government. So far, NIH has been meeting its payments to Anivive, though theyŌĆÖve been slower than usual since Trump took office.

ItŌĆÖs not lost on Edward Robb, chief strategy officer at Anivive and leader of the companyŌĆÖs valley fever vaccine project, that heŌĆÖs developing a vaccine for a relatively unknown infectious disease at the same time as one of the worldŌĆÖs most prominent opponents of vaccines has .

Since taking office as secretary of health and human services, Kennedy has rolled back federal recommendations and endorsements for and vaccines and of a vaccine policy panel at the CDC, replacing many of them with known anti-vaccine campaigners. HHS has little say over vaccines developed for use in animals, but it could derail the regulatory process by which that vaccine is adapted for humans, a process so long and so expensive itŌĆÖs often referred to as ŌĆ£the valley of death.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£WeŌĆÖre nervous but we have no data or anything to say that things have changed,ŌĆØ Robb said. ŌĆ£Have I had lost sleep? Have I had anxiety? Have there been weeks when we think weŌĆÖre doomed? Yeah.ŌĆØ

If NIH continues funding this phase of the project as itŌĆÖs contracted to and the vaccine shows promise, thereŌĆÖs still the matter of finding the funding to conduct phases 2 and 3 of the approval process, when the vaccine is tested on hundreds and then thousands of people. The estimated cost of such an endeavor, Robb says, is $300 million. Anivive canŌĆÖt do it alone. A major biopharmaceutical company like Pfizer or Moderna would need to step in to take it over the finish line.

ŌĆ£Will a major step up and say ŌĆśput me in, coachŌĆÖ?ŌĆØ he asked. ItŌĆÖs looking less likely by the day. In early August, Kennedy close to $500 million in mRNA vaccine contracts with , including Pfizer, Moderna, and AstraZeneca, a move that could further dampen new vaccine research and investment.

For Galgiani, this kind of retreat from vaccine development is irrational. ŌĆ£It makes sense to me that state and federal support for a vaccine would be good for both public health and the economies of endemic regions,ŌĆØ he said.

Whether a vaccine for valley fever moves forward matters not only for the hundreds of thousands of Americans who are likely to get the disease in the coming years, but also for the 6.5 million people who get invasive fungal infections annually around the world. As with valley fever, the overall number of fungal infections is as climate change makes the whole Earth warmer on average.

ŌĆ£Unlike humans, many pathogenic fungi are thriving as the EarthŌĆÖs temperature increases,ŌĆØ the authors of a published last year in the peer-reviewed British medical journal The Lancet wrote. Fungi that cause disease are ŌĆ£quickly adapting to higher temperatures and becoming more virulent and potent.ŌĆØ

A growing portion of these cases are caused by fungi that have become resistant to antifungal medications. Candida auris, a relatively new yeast that has already this year, is . Ninety percent of the Candida auris found in the U.S. is resistant to fluconazole, one of the most commonly used antifungals.

ŌĆ£If we can make a fungal vaccine for valley fever, could one of these companies make a vaccine against Candida infections?ŌĆØ asked Thompson, the fungal disease specialist from the University of California, Davis. ŌĆ£It may just be the first example of vaccines in this field, but it really may lead to some big changes and big improvements for our patients down the road.ŌĆØ

This story was produced by Grist and co-published with . This reporting initiative is made possible thanks to support from the Wellcome Trust.

was produced by and reviewed and distributed by ┬ķČ╣įŁ┤┤.