Nurses are in high demand. Why can’t nursing schools keep up?

Nurses are in high demand. Why can’t nursing schools keep up?

Oscar Mateo dreamed of being an artist, but after he got leukemia when he was 20, his life plans abruptly changed. The compassionate nursing care he received while hospitalized touched him so much that he decided he wanted to provide the same for others.

That impulse led him to the registered nursing program at Mt. San Antonio College in the Los Angeles County suburb of Walnut. But getting there wasn’t easy, as he had to battle competition for limited seats in one of the highest-demand fields in higher education, a career offering purpose, plentiful jobs and potentially six-figure paychecks.

Mateo was rejected three times by Mt. SAC before winning admission. To burnish his resume and win a coveted seat, he earned certification as a nursing assistant and got work experience.

“It’s so competitive and stressful,” Mateo, now 30, said. “It definitely takes a toll on yourself.”

According to , Mateo represents a paradox bedeviling the U.S. nursing landscape. There is enormous demand for nurses, as retirement or burnout push many from the field. Despite tens of thousands of students fighting to get into nursing programs, schools can’t accommodate that demand, for two major reasons: They can’t find enough faculty to teach classes, and there is a dearth of the required hands-on training opportunities in hospitals and health care facilities.

The mismatch has hit California particularly hard, triggering a state audit, legislative proposals and funding initiatives. Some nursing schools want to allow greater use of training technology to widen access — such as high-tech mannequins that simulate heart attacks and other medical conditions. Others warn against that path. In the process, tensions between public and private nursing schools have flared as they battle for resources to expand their programs.

“The demand is so high but there just aren’t enough seats,” said Paul Creason, Long Beach City College dean of business, education and health sciences. “It’s critical to supply the workforce to meet the need, but there are too many obstacles and this will have ramifications for the cost and quality of health care.”

In California, only about a third of 57,987 applications by qualified applicants to nursing school were accepted in 2022-23, the most recent data available, according to the . Nationwide, nursing schools turned away nearly 66,000 qualified applications for bachelor’s and graduate nursing programs in 2023, the reported.

California’s projected shortfall of working nurses is one of the largest in the nation, estimated to grow from 40,790 this year to 61,490 in 2035, according to the . Shortages are projected for both registered nurses, who provide the more advanced health care skills typically acquired in a two- to four-year training program, and licensed vocational nurses, who offer more basic care after certification that usually takes one year to complete.

The most contested resource in nursing education is the hands-on clinical training required.

“You have to have these spots or your program is dead in the water,” Creason said.

California law requires students to complete at least 500 hours of direct patient care under the supervision of nursing staff at a hospital or other health care facility to graduate and qualify to take the national licensing exam. Without that, students can’t finish their degrees and schools can’t increase enrollment.

So the competition for clinical placements is fierce. Requests are soaring just as some hospitals are scaling back on training because their staff nurses are too overloaded to take on more students. More than half of the state’s nursing school programs reported their requests for clinical placements were denied in 2022-23, according to , and 57.2 percent of the state’s 152 registered nursing programs cited a lack of clinical placements as the top obstacle to adding more seats.

Mt. San Antonio College, for instance, lost placements at several sites — one of them fell from 10 to six. This past semester, a hospital withdrew two spots just weeks before classes started, forcing the school to scramble for a replacement. San Antonio Regional Hospital stepped in, opening a night shift for students.

Public campuses argue that their students should have priority for these clinical slots. Private nursing schools — both nonprofit and for-profit — disagree, urging a level playing field.

Reports that some colleges pay for the sought-after slots have riled many campuses, and in the 2022-23 state survey, nine unnamed colleges reported they had provided “financial support” to secure a clinical placement. A 2023 state law now bans such “pay to play” schemes — but college officials say it is difficult to enforce and unclear as to what it covers. Are donations to a hospital’s foundation, for instance, prohibited? What about tuition assistance to nurses who agree to serve as instructors for that college’s students?

With resources tight, state legislators and nursing organizations have begun rallying to better support public nursing programs.

Last year, Gov. Gavin Newsom and the Legislature approved to expand community college nursing programs, including partnerships with four-year campuses for bachelor’s degrees. Beginning this year, another state law mandates health facilities to “” with California community colleges and California State University campuses to meet their clinical placement needs.

Private institutions criticize those efforts as unfair. Samuel Merritt University, a private nonprofit in Oakland, petitioned the state board to add 72 seats to the nursing program at its Sacramento campus, but Cal State Sacramento, Sacramento City College and Sierra College told the board they opposed the request because they were losing clinical sites and worried about nurse burnout from training students. The state board approved the 72-seat increase, in August, after the university found clinical placements outside the immediate Sacramento area.

“What we find to be the most frustrating is the state schools, the four-year institutions and the two-year institutions, they’re kind of banding together to prevent any growth by the private schools,” said Steven Rush, dean of Samuel Merritt’s college of nursing.

Creason, of Long Beach City College, argues that community colleges should get priority for state funding and clinical placements because they deliver quality nursing education at a significantly lower cost than private programs, and typically to students who reflect the state’s cultural and linguistic diversity.

California nurses’ organizations agree, saying that community colleges and CSU campuses in particular offer a pipeline to nursing jobs for lower-income, first-generation students of color and that these graduates provide culturally sensitive care.

Creason said the total cost for a Long Beach City College two-year associate degree in nursing – the college’s most popular major along with business – is about $5,000. Under a newly established partnership with Cal State Long Beach to jointly prepare students for a four-year bachelor’s degree in nursing, the total cost would be about $43,000, he said.

That compares — a private, for-profit institution that runs the state’s largest nursing program, with campuses in Los Angeles, Orange County and the Inland Empire.

But the more affordable public nursing programs are also far more difficult to get into. Long Beach’s admission rate is about 3.3%, with room for 80 students among 2,400 applicants each year, although the partnership with Cal State Long Beach will allow it to grow to 120 seats in about two years, Creason said.

West Coast, by contrast, has a 100 percent admission rate and an .

That ease of entry is why Oscar Mateo was close to enrolling at West Coast before finally winning admission to Mt. SAC on his fourth try. He said he would have needed to take out a loan of more than $100,000 to afford West Coast but was so driven to become a nurse he would have been willing to make that investment. He was ecstatic when he got his financial aid letter and saw that state grants and fee waivers would cover the entire cost of his nursing program aside from books.

“I was so happy. I couldn’t believe it,” he said. “Once I was in Mt. SAC, it was a no-brainer to go to a community college. The low cost made it so enticing and the respect the school has from the hospitals are big reasons for attending this program over others.”

For Ray Ayranian, the heftier tuition and fees at American Career College, a private, for-profit institution, are worth it. Ayranian, who was inspired to pursue nursing after seeing the care given his sister when she underwent neurosurgery, started out at Pasadena City College. But he said he wasn’t a great student and thought the private-school route would be easier — and faster. He and his parents took out a loan for about $30,000 to pay for the 12-month licensed vocational nurse program, he said, and he plans to pay off the debt by working extra shifts once he earns his degree and gets a job.

“I just wanted to do something fast because I’m a pretty hands-on person,” he said.

Representatives for American Career College and West Coast declined to comment.

One potential solution to ease the crunch is state financial incentives to hospitals and other medical facilities to provide more clinical placement slots. to nurses and other health professionals who mentor nursing students, while , South Carolina and Alabama are or other financial incentives. to give a $2,000 tax credit to nurses who provide at least 200 hours of clinical training is pending.

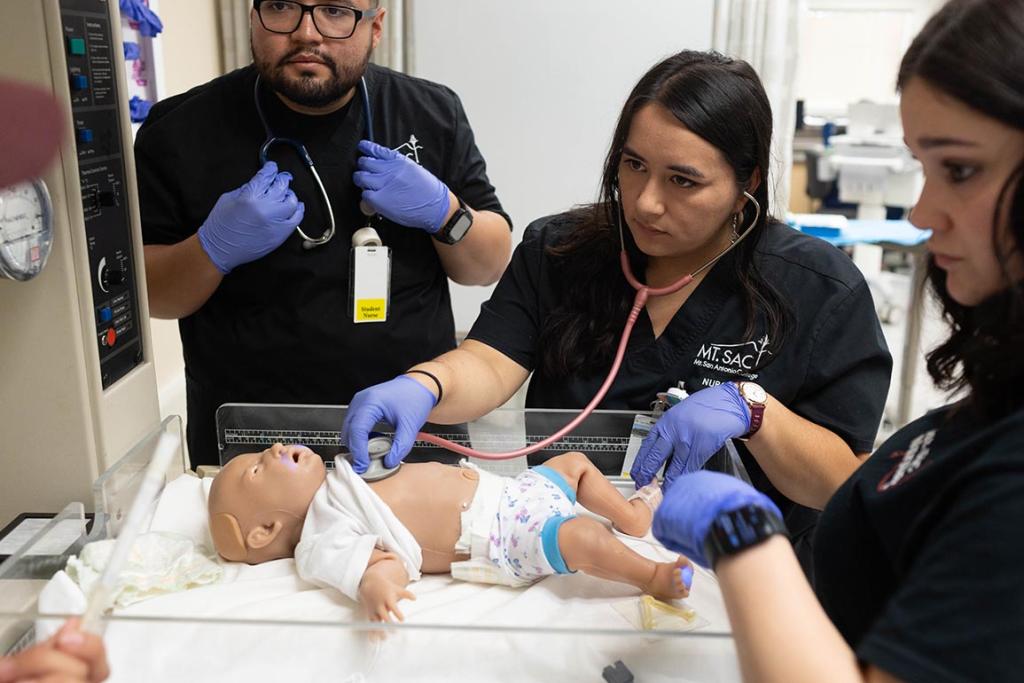

Another idea is expanding the use of technology. At Mt. SAC, for instance, classrooms have high-tech mannequins that can be programmed to blink, shriek and simulate a variety of medical conditions, including heart attacks, bleeding, respiratory failure — even giving birth. offer interactive 3D environments with animation or actors simulating patients. The technology, which is used in many states, allows nursing students to practice diagnosing and treating medical conditions in a low-stakes environment.

Given the shortage of clinical placements, some nursing educators argue that accredited programs with high student licensing exam pass rates should be allowed to balance simulation training with hands-on training, rather than meet the state’s minimum 500-hour requirement.

Michelle Mahon of the National Nurses United union says better working conditions for nurses would draw back more of those who got burned out and left the field. That, she said, would help ease the pressure to create more nursing school seats.

At Mt. SAC this summer, a group of students doing simulation training was directed to examine a mannequin that was simulating a 72-year-old woman who had undergone gall bladder surgery and returned home. The mannequin, nicknamed Apollo and made of silicon, synthetic plastic polymer and other materials, sported hard legs but a soft, rubbery feel to most of the rest of the body.

The clinical instructor, Maria Stefanidis from nearby San Antonio Regional Hospital, assumed the voice of “Mrs. Smith,” complaining of nausea and sharp pain in her abdominal area.

Paul Song, playing the role of a home health nurse, checked the mannequin’s blood pressure, heart rate, temperature and respiration – all computer programmed. Stefanidis reminded him to assess the incision area for redness and warmth, a potential sign of infection, and guided him on the proper way to check for abdominal sounds. He told Stefanidis he suspected a blockage in the intestines and possible infection because of the elevated vital signs.

“Good assessment,” Stefanidis said. “So what are we going to do about that?”

“The best course of action would be to call the doctor and let him know,” Song said.

Andrew Santana, Mt. SAC’s Simulation Lab specialist and instructor, said the campus plans to expand its technology offerings with a new health careers building and advancements such as mannequins programmed with artificial intelligence that are able to spontaneously converse with students.

Eileen Fry-Bowers, dean of nursing at the private nonprofit University of San Francisco, is among those who believe that accredited programs with high student licensing exam pass rates should have more flexibility in balancing simulation and hands-on training. No evidence supports the state’s requirement of 500 hours of direct patient care as a threshold for positive patient outcomes, she said.

“This idea that direct care is the be-all and end-all of clinical education is not supported by research,” she said.

Others say technology can never replace the human-to-human connection. Nicole Ong, a Mt. SAC nursing student who worked as a certified nursing assistant before starting her RN program, said experience with real people is crucial for learning how to bond with patients in their most vulnerable moments.

“You have to get trust from a patient and you can’t get that from a mannequin,” Ong said.

was produced by , a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education, and reviewed and distributed by ¬È∂π‘≠¥¥.