How do you build a house that could get grandma through the apocalypse?

How do you build a house that could get grandma through the apocalypse?

Since wildfires tore through his Yunesitãin community in 2017, Russell Myers Ross has been pursuing a dream: building a fire-resistant house that will survive everything climate change can throw at it.

ãI sometimes joke that we could make this good enough to have a grandmother stay in here and live through the apocalypse,ã Ross says with a laugh.

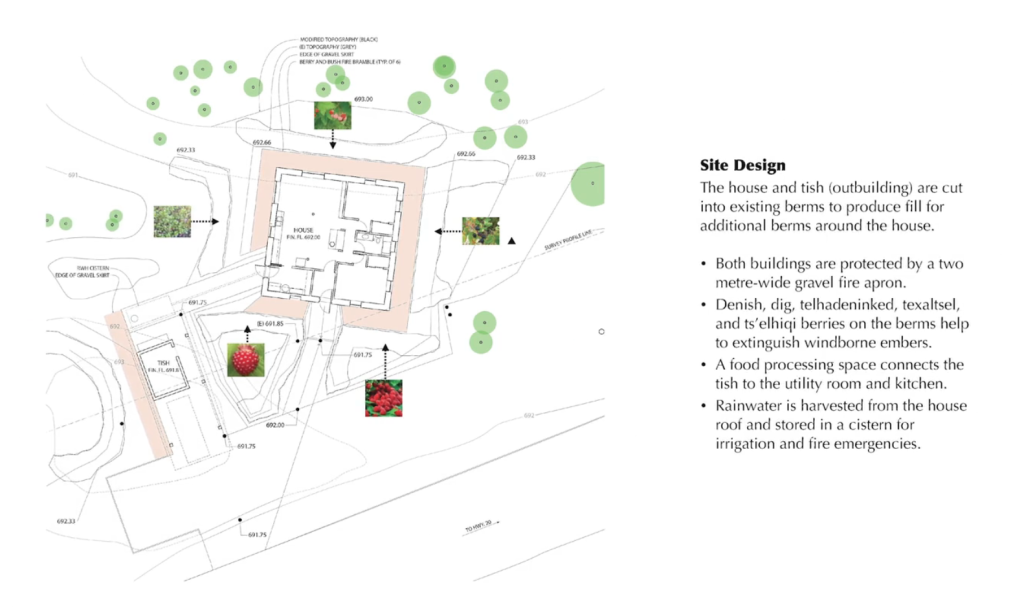

His community, one of six in the Tsilhqotãin Nation, was severely damaged in the 2017 wildfire season. Afterward, Ross, who was elected chief at the time, began envisioning a housing solution. The design includes a white, highly reflective metal roof that deflects heat and is fire-resistant, gravel lining the house and sprinklers facing the walls ã using easily accessible technologies for a resilient home that makes sense for the dry, hot interior of British Columbia.

The fire-resistant house is designed to be built with high-quality materials that fend off flame and smoke while incorporating the elements of traditional Yunesitãin pit homes ã round and set in the ground. Ross tells that he wants more for his community than the houses introduced with the Indian Act, which were often low quality.

ãWe should build houses that are better than the ãINAC shacks,ã ã Ross says, referring to the nickname for houses provided by the former department, Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (which has since had many similar names and is now two separate federal departments).

In 2016, Ross began talking to professor John Bass from the University of British Columbiaãs school of architecture and landscape architecture to realize his vision, and work took off in earnest in 2018 after the destructive wildfires. They recently released that include a three-dimensional walk-through of the design and community members speaking to the importance of getting this house built.

ãThis work has been done. Itãs just about finding a funder to get a prototype,ã Bass says.

Outdoor space includes space for a fire and a smokehouse

The 2017 fires burned 2,326 square kilometres around Yunesitãin ã a region almost as big as Metro Vancouver. Since then, the Yunesitãin government wrote a report on how to prepare for future wildfires, which included more resilient housing. The Tsilhqotãin National Government has been revitalizing , which was outlawed by the province for decades, even though it helps clear the forest understory to reduce the chance of highly catastrophic fires.

In a by the Tsilhqotãin National Government, community members said their top housing concerns are the need for major repairs, the high cost of energy, overcrowded homes and mold ã which, like smoke, is a . The concerns made it crystal clear to Ross that people need higher-quality housing. In a 2019 survey done by Yunesitãin, people also said they wanted storage sheds, renewable energy options, smokehouses, gardens and outdoor space.

Ross now works in an array of positions, including advancing fire stewardship in the Dasiqox Tribal Park, led by Yunesitãin and the Xeni Gwetãin First Nations, and being the online program and operations manager to the Bachelor of Indigenous Land Stewardship at the University of British Columbia, but remains committed to the fire-resistant house. He says Indigenous concepts of homes are expansive, reflecting each nationãs territory, history and values. Building a culturally specific home may mean prioritizing emissions reduction or hiring community members as builders. It can mean ample outdoor or shared community spaces.

ãItãs trying to get a feel of what a liveable space is for people,ã Ross says.

For this design, it means extending beyond walls ã the outdoor space, which includes plans for a fire pit, space to process meat and a smokehouse, is just as important, he says, as whatãs built indoors.

Because so much family time centres around preparing and enjoying food together, the space was designed so that residents can move seamlessly from inside to the fire and food-processing area outside. ãThat was the most important cultural idea ã living happens outside as much as it happens inside,ã Bass says.

They wanted the home to reflect a Tsilhqotãin pit house, and to be simple and durable. Although this design is not round like a pit house, they tried to emulate the feeling by placing a central skylight above a stove, marking the centre of the home and columns along the edges.

The design is made to fit Yunesitãinãs needs, but Ross hopes the template can be adapted for other Indigenous cultures ã imagining, for example, a design that reflects the long houses of coastal First Nations.

Reflecting membersã desire for sustainability, the house includes a heat pump for cooling during heat waves, solar panels for energy efficiency, a membrane to prevent mold and high-efficiency air filtration (called HEPA) for smoke. The design meets step four of the BC Energy Step Code, which is almost at a passive house level. A is a voluntary standard to make a building highly efficient due to passive elements of its design (like being well-sealed and using high-quality materials and insulation) versus relying on active heating and cooling.

The home is also designed with heat recovery ventilation (HRV) technology, which replaces stale indoor air with fresh outdoor air without compromising the energy-efficient seal of the home.

Some technology, like the HEPA filtration, is simple to install and available in hardware stores but still rarely found on reserve, Bass says. ãTheyãre commonly understood but cost money,ã he explains.

In addition to gravel around the house, fire protection includes naturally fire-resistant berry hedges that can capture burning embers from fires. It includes rainwater harvesting for irrigation and fire emergencies, and sprinklers to spray against the walls and moisten them to help prevent them catching fire.

The walls were one area culture and economics came into play ã Bass wanted metal walls, but community members wanted wood. The final compromise was to use charred wood, which has a scorched exterior. ãItãs harder to ignite ã but in an intense fire, itãs going to burn,ã Bass says.

Ross says they were considering what resources they have available.

ãPart of it, for us, was like, ãWhat can we build from our own landscape?ã ãÎ We were trying to think long-term in that regard,ã Ross says. He was thinking of what resources can be depended on and what jobs can be locally supported and maintained over time. ãIf weãre going to design something, weãve got to design it with all of our interests in mind,ã he adds.

Bass says that he has learned how important it is to adapt when working with capacity-strapped communities. In this case, he and his students had to focus on designing with Yunesitãin ideas at the centre, even if that meant deadlines extended outside of the academic calendar. ãItãs their project,ã he emphasizes. The goal is to help a community realize their vision ã not ãburdenã them with imposed timelines.

The housing problem requires ãmany solutionsã for many First Nations contexts

Like Yunesitãin with the University of British Columbia, other B.C. First Nations are forming partnerships to build housing that reflects their cultures and visions for the future, including the realities of climate change.

Bass and his students also worked with the HaûÙɫzaqv (Heiltsuk) Nation to build four tiny homes. The community faces a similar housing shortage and is looking for ways to install clean energy infrastructure and build to survive heat waves, sea-level rise and wildfires.

On Vancouver Island, Cowichan Tribes is building Riverãs Edge, a project of over 200 rental townhomes, with priority given to community members for some of the below-market units. To account for possible flooding of the Cowichan River, the development involves removing sediment from the river to prevent build-up and deepening the river to prevent overflow. That sediment has been used at other construction sites, with royalties going back to the nation.

ãWeãre obviously experiencing climate chaos,ã Renûˋe Olson, interim chief executive officer of Cowichanãs Khowutzun Development Corporation, says. ãSo to mitigate when floods will happen, weãre very conscientious about sediment removal.ã

Cowichan Tribes developed its project through the BC Builds program, run by the Crown corporation BC Housing. It focuses on rental housing, keeping rental costs down through low-interest financing, finding ways to speed the development process and utilizing public lands.

ãOne of the reasons housing has become out of reach, especially in dense residential [areas], is shareholders were demanding a rate of return,ã Olson says. ãThis is why this BC Builds program is so important ãÎ Itãs about creating opportunities for community land.ã

Cultural elements of Riverãs Edge include spacious indoor kitchens, a shared outdoor kitchen, a community garden and native plants.

Cowichan has more than 5,500 citizens, and the plan is for money generated from the development to go back into building homes on reserve ã where many more are needed.

ãIt takes many solutions, different solutions, to tackle this complex problem,ã Olson adds.

Construction and housing costs higher than ever

Ross says the main obstacle to getting the first prototype house built is funding ã not just enough to get the walls up, but to benefit the community.

Since COVID-19 hit in 2020, construction costs have skyrocketed, Bass explains, all while housing problems also ballooned. Itãs now harder than ever to catch up, he says, but theyãll be contacting government, industry, foundations and private donors for potential support.

For Ross, getting this house built is just one step in a larger vision. He wants to build more high-quality homes, but also a local economy, including training and hiring members to build and maintain the homes ã something that would require a locally owned mill. He sees a self-sustaining future.

ãThe idea was to have a circular economy ã so weãre building from our community, but with the hope that we could build enough capacity to help our other surrounding communities,ã he says.

was produced by and reviewed and distributed by ôÕÑ¿åÙÇÇ.