What would âconcealed carry reciprocityâ mean for states with tighter gun laws?

What would âconcealed carry reciprocityâ mean for states with tighter gun laws?

Over the last three decades, carrying concealed guns in public in the United States has become . First, in the 1990s, states began to guarantee permits to anyone who could legally own a firearm. Then, beginning in the mid-2000s, states started removing permit requirements altogether.

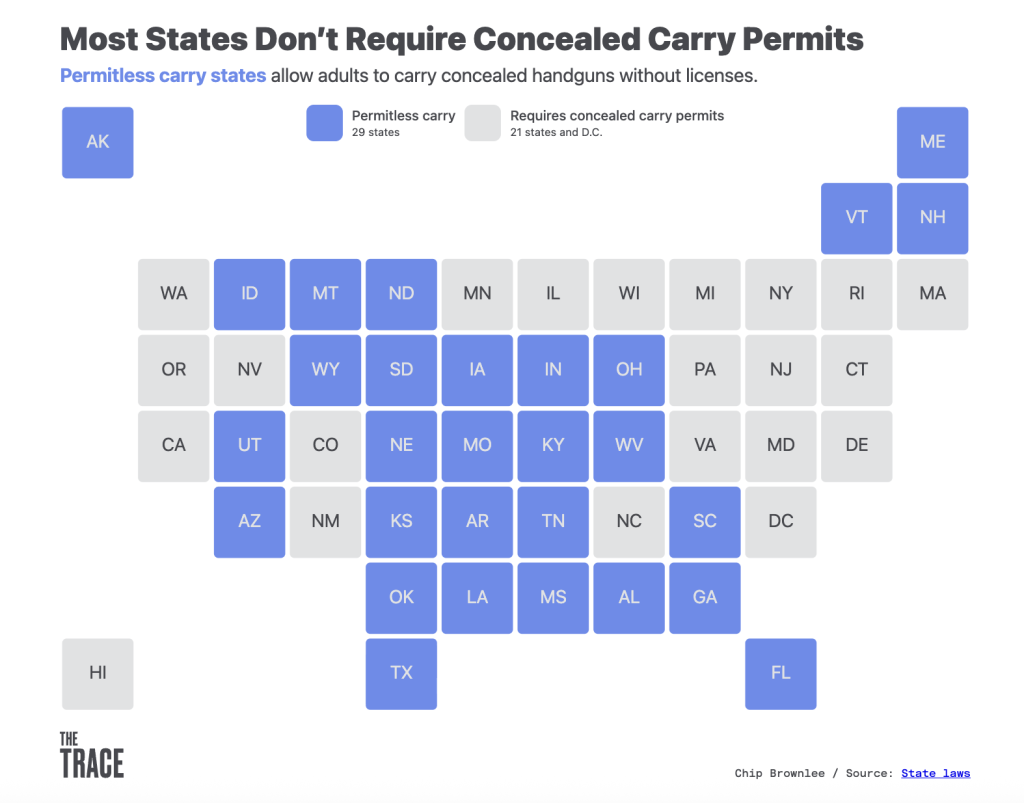

Now, â 29 as of 2025 â require no license to carry a loaded gun in public, a policy known as permitless carry. But what happens when a resident of one of those states wants to carry their handgun in one of the 21 states that does require a permit?

That led a reader to send in a question concerning concealed carry reciprocity, or when one state recognizes the concealed carry permits of another. The reader asked:

âIf your state has decent laws, which Michigan where I live has (ok) gun laws, the constituents of my state still have to follow our stateâs laws. But could someone from Louisiana come here and have the very lax laws of their state apply to them while visiting Michigan? Is it a race to the bottom?â

Itâs a timely question. Congress may vote as soon as this month on a bill that would require national concealed carry reciprocity, effectively allowing the residents of those 29 permitless carry states to carry guns nationwide without a license. dives into the specifics of concealed carry reciprocity, and what a nationwide law â a longtime gun rights goal â would look like.

What is concealed carry reciprocity?

Concealed carry reciprocity refers to the patchwork of state laws, policies, and agreements that determine whether one state honors concealed carry permits from another state, allowing permittees to travel across state lines with their guns.

Importantly, âreciprocityâ is often not mutual: Recognition of out-of-state permits varies widely, and many arrangements are unilateral rather than formal two-way agreements.

Some states adopt broad recognition â for example, North Carolina and the readerâs home state of recognize permits from any state.

Others condition recognition on comparable standards, including fingerprint-based background checks, mental health disqualifiers, age requirements, or live-fire training. For instance, Minnesota recognizes permits from 33 states whose requirements its attorney general has deemed similar to Minnesotaâs.

From there, it can get even more complicated. Washington state â which wonât recognize other statesâ permits if they donât require mental health background checks, or if they issue permits to people under 21 â only recognizes 10 statesâ permits, and of those, sometimes only honors enhanced permits that have stricter eligibility requirements like live-fire training.

At least 10 states, including California, Oregon, and New York, and the District of Columbia, do not honor any out-of-state permits.

How does permitless carry affect reciprocity?

Permitless carry both simplifies and complicates reciprocity. In the 29 states that have passed permitless carry, both residents and nonresidents can carry a concealed firearm without a permit. That means that if you are visiting one of those states, you donât need a permit to carry as long as you arenât prohibited from possessing guns under that stateâs or federal laws.

For example, an Alabama resident doesnât need to get a permit to carry in Mississippi or Georgia, and vice versa.

But the same is not true for residents of permitless carry states who want to carry in a state that requires a permit. In that case, you still need a license from your home state.

âRight now, in general, if you are from a state with permitless carry and you travel to a state that requires a permit, you still need a permit to carry,â said Alex McCourt, a professor at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and assistant director of the Center for Law and the Publicâs Health. âPermitless carry doesnât necessarily transfer.â

Thatâs why nearly all states that have permitless carry still provide a process to obtain a carry permit, and why many gun owners in permitless states still apply for them: to ensure they can legally carry when traveling or commuting to another state with reciprocity.

Is it a ârace to the bottomâ?

The reader who posed the question worried that reciprocity could mean the weakest state laws effectively override stronger ones. The reality is more complicated.

When it comes to carrying a gun, the laws of the state youâre carrying in apply. That means reciprocity is not a blanket permission slip. âTypically, the only thing that really transfers from state to state is recognizing the validity of the permit,â McCourt said. âFor example, if Michigan says you canât carry in certain locations, that applies to everybody carrying in Michigan â even if your home state doesnât have those restrictions.â

To build on that example: Say a permit holder from Louisiana is visiting Michigan, which prohibits carrying guns in bars, churches, schools, day cares, and sports arenas or stadiums. Even though Louisiana doesnât have all the same place-based restrictions, the Louisiana visitor would still need to follow Michiganâs rules while carrying in Michigan.

But when it comes to acquiring a gun, the laws of the gun ownerâs home state generally apply. Thatâs where the ârace to the bottomâ concern comes in: A person from a state without universal background check requirements, like Louisiana, could purchase a gun in a private sale without a background check and still legally carry that gun in a stricter state like Michigan, where the same purchase would have required a background check had it been done there.

âMichigan couldnât say, âYou didnât go through a background check, so you canât have that gun here,â because the person followed Louisianaâs rules when acquiring it,â McCourt said.

What would nationwide reciprocity look like?

For years, gun rights advocates and the gun industry for a federal law requiring all states to recognize one anotherâs permits â or lack thereof. Several bills have been introduced in Congress, including the . If passed, it would bar states from fully enforcing their laws on gun carrying. The consequences would be sweeping.

The legislation would allow any person who is licensed or âentitledâ to carry a concealed firearm in one state to carry a concealed handgun in any state. As written, the bill appears to go beyond mandating that states honor other statesâ permits. It would also effectively create nationwide permitless carry for people whose home states have such laws on the books.

âWhat I understand from this bill is that if you are in a state that allows an individual to carry a concealed weapon without a permit, you will then be permitted to carry a concealed weapon without a permit in every state in the country,â U.S. Representative Dan Goldman, a Democrat from New York, said during a committee hearing on the bill in March.

Goldman pointed to from The Trace that showed that states that have enacted permitless carry saw violence increase after the bills went into effect. âNow essentially the entire country will become a permitless country,â he said.

While there isnât research directly measuring the effects of reciprocity itself, the evidence on loosening concealed carry requirements generally is fairly consistent, said Cassandra Crifasi, a researcher and co-director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Solutions.

âEverything we know about what happens in states when theyâve removed permitting requirements â whether itâs violent crime, shootings, shootings by police, any of those sorts of things,â Crifasi said, âthe best evidence suggests that those things would go up and therefore make everyone less safe.â

Critics also warn the bill would undermine the remaining training and licensing systems in states with stricter laws like New York, New Jersey, or Massachusetts. âMany states that require a permit also require you to get training,â McCourt said. âNationwide reciprocity could neuter those training requirements nationwide.â

Proponents often compare national concealed carry reciprocity to driverâs licenses. But Crifasi said the similarities are only superficial.

âWith driver's licenses, you have to take a vision test and a written test, and then you have to pass a proficiency testâ that requires actually driving a vehicle, she said. But concealed carry permit requirements vary widely from state to state, with most .

âWeâre comparing apples and pineapples when you talk about concealed carry and a driverâs license, because in more than half of states now you donât need to get a license at all,â Crifasi said. âThat would be like saying, âOh, you live in Texas and you donât need a driverâs license? Cool, go drive in New York City without getting a driverâs license, no problem.â It doesnât logically track the same way.â

Could the law pass?

The bill has broad support among conservative lawmakers, with 189 Republican co-sponsors in the House. It already cleared a committee vote in March, and in October, it was placed on the House calendar, meaning it could be brought up for a floor vote at any time. President Donald Trump has to sign it if it reaches his desk.

While itâs possible or even likely for the bill to pass the House, it faces a tougher challenge in the Senate, where it would need 60 votes â and thus Democratic support. No Democrats are likely to support the law.

Opposition from law enforcement may also peel off Republican support. In November, two of the nationâs largest law enforcement associations â the Fraternal Order of Police and the International Association of Chiefs of Police â came out against the bill, arguing that it could place officers in both legal and physical danger. âOfficers would be expected to interpret and apply laws from all 50 states in real time, without reliable means to verify an individualâs eligibility to carry concealed weapons, especially those from permitless carry states where no physical permit exists,â the groups wrote in a .

The legislation allows lawsuits against officers and agencies for arrests or detentions that violate its provisions. That could make it difficult for police to enforce concealed carry laws at all, since an officer could be placing themselves in legal jeopardy if they take any action â like temporarily securing a firearm during questioning â that could later be construed as violating a personâs concealed carry rights.

That legal ambiguity, plus incentivizing more frequent gun toting in more places, could place officers in danger. âThis leaves law enforcement unable to confirm lawful possession during encounters, creating confusion and heightened risk in high-stakes situations,â the law enforcement groups wrote.

Still, gun rights groups are pressuring Republicans to prioritize the bill despite law enforcement opposition. ââShall not be infringedâ does not just apply to law enforcement â it is the God-given, constitutionally protected right of the People,â the Gun Owners of America wrote in a November 25 to House Speaker Mike Johnson responding to the law enforcement opposition.

Even if the bill doesnât pass, gun rights proponents are also working in the courts. The Supreme Court could decide whether it takes a case from in which a New Hampshire plaintiff is challenging Massachusettsâs permit requirements for nonresidents. In September, New Hampshire and 24 other states to take the case. Should the court agree and strike down the law, it could imperil similarly strict laws in other states and expand interstate gun carrying nationwide.

The bottom line

Reciprocity today is a patchwork. Some states recognize many permits, others only a few, and permitless carry doesnât automatically transfer across state lines. But a federal reciprocity law or a broad ruling from the Supreme Court could dramatically expand where people can carry â and, experts warn, weaken training and safety standards across the country.

âItâs supposed to make things simpler,â McCourt said, âbut in reality it could be more confusing â and more dangerous.â

was produced by and reviewed and distributed by ÂéśšÔ´´.