The climate solution sitting in Americaās trash

The climate solution sitting in Americaās trash

Cutting food waste is a huge potential climate win. Why are we ignoring it?

In the United States, climate change is polarizing, but one environmental challenge draws rare bipartisan agreement: . Even as the Trump administration rolls back key climate and environmental protections, in July, senators from both parties reintroduced ā one longtime driver of unnecessary waste. In September, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency launched a and keep edible food out of landfills. Under the Biden administration, the U.S. unveiled a and expand recycling of organic waste.

Despite this rare consensus, progress has been slow, and Sentient report. In 2023, the U.S. still , according to the food waste nonprofit ReFED. Food waste is responsible for 8-10% of all global emissions ā about five times the emissions from the entire aviation industry. The United Nationsā Food and Agriculture Organization estimates that if food waste were a country, it would be the, after China and the U.S.

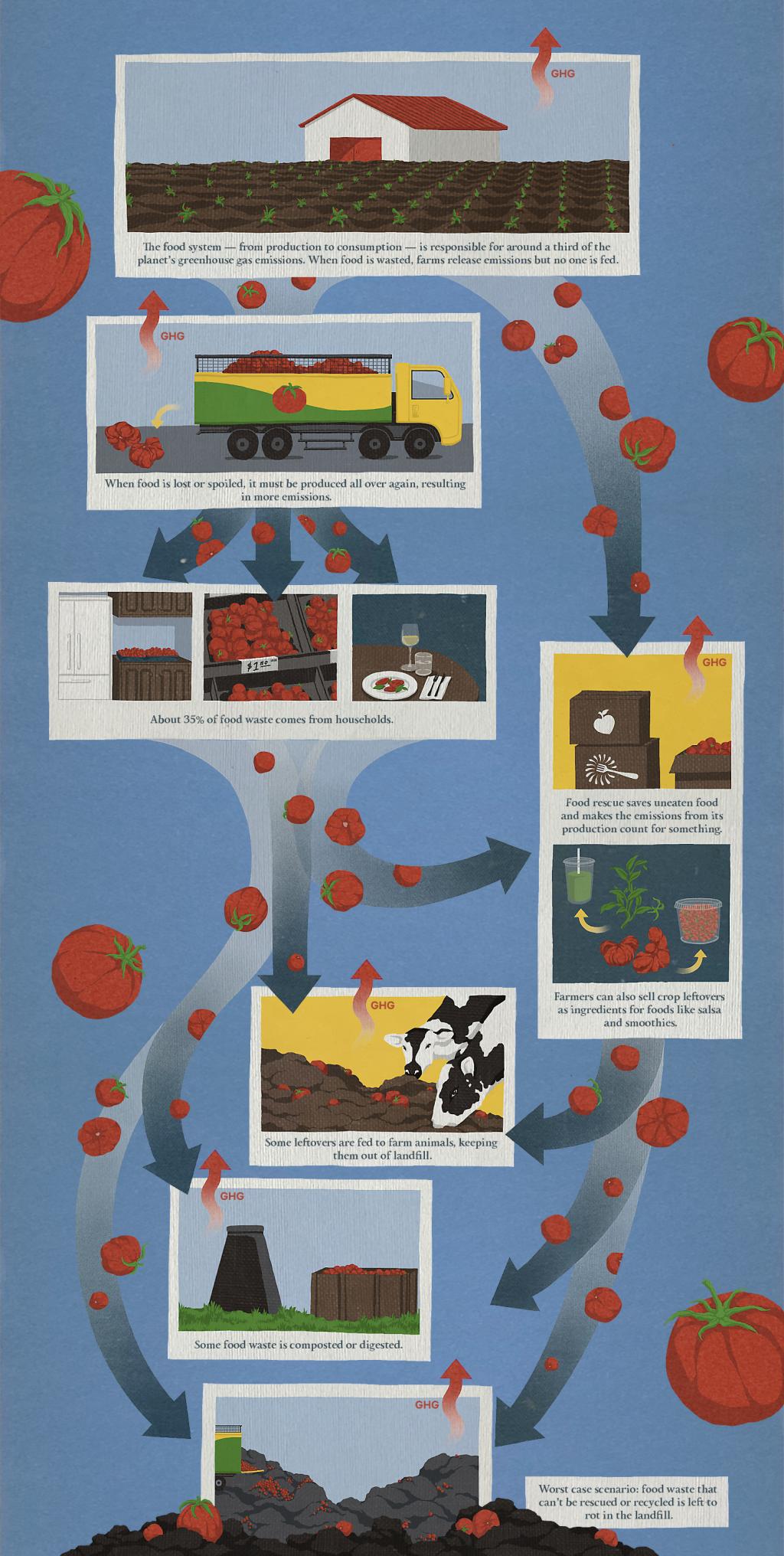

Experts tell that the problem persists because political follow-through is limited, climate action still focuses heavily on energy and transportation, and ultimately, food waste itself is difficult to tackle. It occurs at every stage of the supply chain, from farms to fridges, making comprehensive action essential.

Itās also a missed opportunity, especially since wasting food is widely seen as wrong. āNobody wakes up wanting to waste food,ā said Dana Gunders, president of ReFED, during a summit at New York City Climate Week on Sept. 22.

Many people donāt realize that food waste reduction is a crucial and often overlooked climate strategy. Addressing food loss and waste has enormous climate potential, ābut itās still an underexplored area,ā says Brian Lipinski, head researcher on food loss and waste at the environmental research nonprofit World Resources Institute.

The climate cost of wasted food

Most food waste happens in homes, restaurants and retailers, but nearly all of its climate impact is already baked in by the time the food is thrown away. Every piece of wasted food squanders all the emissions that went into producing and transporting that food. About ā when land is converted from forests or grassland to farmland, when resources are used to grow crops or raise livestock, during transport, in which most vehicles run on diesel or gasoline, and during cold storage. Once that food is tossed, those emissions are wasted. Only come from the disposal process.

When people are wasting food, āin many ways, we are throwing out a lot of water, a lot of land, a lot of fertilizer, natural habitat, a lot of things,ā Paul West, a senior scientist at the climate nonprofit Project Drawdown, tells Sentient.

Fruits and vegetables make up almost half ā 44% ā of all U.S. food waste, . Meat and seafood, though also quick to spoil, are wasted less often because they are more expensive.

But wasting even a small portion of a than wasting the same amount of fruits, vegetables or chicken, says West. Thatās because producing beef requires vast amounts of land, water and fertilizer, and cattle also release methane ā a short-lived but powerful greenhouse gas ā with each cow burping about . āIf we are going to eat beef and dairy, make sure not to waste it,ā says West.

Why prevention matters most

Experts see reducing food loss and waste as one of the most impactful and practical ways to slow the warming of the planet. Project Drawdown calls it an solution ā a measure that can rapidly slash emissions using tools we already have, without waiting for new technologies or nature-based fixes. Other such measures include halting deforestation and .

āPreventing food from becoming waste is really the most effective solution, not only from an emissions perspective,ā says Minerva Ringland, senior manager of the climate and insights team at ReFED, ābut itās also saving the most money and keeping everyone fed as much as possible.ā

In the United States, , while 18% comes from manufacturing and 17% from food service, and 24% happens on farms. Household waste is high because people often buy more than what they need, especially in bulk, misinterpret date labels, prepare too much food and may not know how to store or repurpose ingredients. Limited access to composting programs also makes it harder for consumers to avoid landfills.

Experts suggest households can curb waste by planning meals, buying only whatās needed, using smaller portions and repurposing leftovers. Emily Broad Leib, director of the Harvard Food Law and Policy Clinic, says the U.S. needs a national consumer awareness campaign, similar to the United Kingdomās Many people donāt realize how significant the issue of food waste is, she says ā not just for the environment but for their own finances.

But reducing food waste at home is not just about telling people to be more careful or intentional about their purchases. After all, food waste is rarely intentional. Maybe you buy an ingredient for one recipe and never use the rest, or and they go bad. Lipinski says that retailers and food service providers can help consumers avoid waste by offering smaller portions, clearer guidance and smarter packaging.

Government agencies can lead by example in reducing food waste in their dining halls, federal buildings, schools and military bases by requiring vendors to donate surplus food, Broad Leib suggests.

These strategies are worth the effort because preventing food waste at its source offers climate benefits about 10 times higher than other strategies since it reduces the need for producing additional food.

Beyond prevention, the EPA identifies donation and ā as the most preferred approaches. However, , and both strategies require energy for transport, storage and processing. According to the EPA, using wasted food as animal feed, leaving crops unharvested, composting and anaerobic digestion do much less to offset the environmental impacts of food production than preventing food waste in the first place.

Where most wasted food ends up

Most of the countryās surplus food still ends up in landfills, compost facilities, incinerators or anaerobic digesters, according to ReFED. Only about 2% is donated. Food makes up nearly a that ends up in landfills.

In landfills, food waste decays and releases methane, a gas 80 times more potent than carbon dioxide at trapping heat over a 20-year period. Landfills produce 17% in the U.S., after oil and gas and livestock digestion. A majority of the methane released from landfills in the U.S. comes from food waste, . A separate analysis by ReFED estimates that surplus food generates nearly each year.

Improving landfill management is one of . To capture or reduce methane emissions, some landfills install systems that divert landfill gas so that it can be burned for energy and sold to industries or utilities, helping replace fossil fuels. Methane that cannot be used for energy is typically burned off using flares. Another approach uses ā layers of organic material that foster bacteria that convert methane into carbon dioxide and water. Leak detection and repair programs can monitor methane leaks using drones, satellites or on-site sensors, which helps operators spot and fix leaks.

Encouraging composting instead of putting food scraps in landfills also helps. But West says that while composting and landfill management matter, āyouāll have many times more impact if you stop the waste in the first place.ā

A change to these policies could help curb food waste

For something so uncontroversial, food waste has proven remarkably hard to fix.

In 2015, the U.S. set an ambitious goal of halving food loss and waste by 2030 ā a target experts say is quickly becoming out of reach. No , researchers from ReFED and University of California Davis found in an analysis published in January. They warned that food waste levels are unlikely to fall without stronger state and federal action focused on prevention measures such as standardized date labeling, food rescue and repurposing. Current policies, they noted, focus too narrowly on recycling methods like composting rather than addressing the problem across the entire food system.

Standardized date labeling is one of the most cost-effective fixes, ReFED argues. In the U.S., . Many U.S. consumers donāt know the specifics, but there is no national standard for date labels. Some products have āSell byā dates, others have āBest beforeā dates, and still others have āUse byā dates ā and they often mean different things in different states. The dates on packaging are ānot designed for consumers to understand clearly,ā Ringwald says.

As a result, many people toss food after the printed date, assuming it is unsafe to eat. This confusion leads Americans to discard about worth $7 billion each year. āSell by,ā āBest before,ā and āUse byā dates usually indicate how long a product will stay at peak quality, not whether it is still safe to eat. According to the USDA, the date shows when the product will taste or look its best. āSell byā indicates how long a store should keep a product on the shelf, and is meant for communication between manufacturers and retailers, but is often mistaken by consumers for an expiration date.āUse byā is the last date the product is at its best quality.

If you have a can of beans in your cupboard with a āSell by,ā āUse by,ā or āBest beforeā date, it does not necessarily mean you should throw it out once that date passes. ReFED says that many foods such as canned goods, nuts and dry packaged goods can remain edible past the printed date.

To address this, : āBest if used byā and āUse by.ā āBest if used byā indicates product quality: it may not taste its best, but it is still safe to consume. This label is recommended for use for canned goods, bread, raw meats, frozen foods and pasteurized products. Meanwhile, āUse byā would apply to highly perishable items or those that pose a risk to safety over time, like deli meats, unpasteurized milk and soft cheeses, and smoked seafood. These products should be eaten by the date on the package and tossed afterward. If passed, the bill reintroduced in the Senate would make that standard nationwide. Similar measures have been introduced in the past, but have not advanced. ReFED estimates that standardizing labels could keep at least 425,000 tons of food ā or 708 million meals ā out of landfills each year.

āEven though the issue is something that both Republican and Democratic administrations have cared about and worked on, thereās a lot of momentum that gets lost in between administrations,ā Broad Leib says. The lack of sustained policies, she adds, has prevented the U.S. from making meaningful progress in reducing food waste.

āPockets of progressā

Still, there are signs of progress, especially at the state level. Thatās probably where weāll see more momentum under the Trump administration, says Lipinski.

In 2024, California signed the countryās first legislation to adopt a clear two-label system on food products. Starting July 1, 2026, .

Another is the implementation of state-level mandates that prohibit sending commercial food waste to landfills. States including California, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Vermont and Massachusetts have enacted such bans. However, a study published last year found these ā except in Massachusetts, which succeeded in reducing the amount of food waste sent to landfills by 13%. Researchers found that Massachusetts has the countryās most extensive food waste composting network, making it easy and low-cost for businesses and households to follow the ban. The stateās rules are straightforward, with no exemptions, and authorities conduct far more inspections and issue more fines for violations than in other states. These differences point the way toward better implementation in other states.

Experts say that stronger incentives for grocers and restaurants to donate food could also make a significant difference. Some states, like California, now require some commercial establishments to donate edible food that they would otherwise throw out.

āWeāre seeing pockets of progress everywhere,ā says Ringwald. Because food waste is a complex problem, she adds, āWeāre going to need a lot of solutions.ā The key is turning these scattered successes into coordinated and sustained action across the supply chain, which can save money, slash emissions and put food on tables.

is a partnership between and , with visual reporting by Floodlightās Evan Simon.

was produced by and reviewed and distributed by Ā鶹Ō““.