Trump-fueled gas boom has fenceline Gulf Coast communities on edge

Trump-fueled gas boom has fenceline Gulf Coast communities on edge

For more than a decade, Rebekah Hinojosa has fought the buildout of liquefied natural gas terminals near the Texas border with Mexico. She wants to save the pristine land fronting the Gulf of Mexico from that would carry billions of cubic feet of gas all over the world.

Watch the that accompanies this story.

Using what they call a ādeath by a thousand cutsā strategy of opposition, Hinojosa, a founder of the environmental nonprofit South Texas Environmental Justice Network, and her fellow advocates have traveled the world. Theyāve pleaded with banks, politicians, insurers, and companies to drop their support for the LNG terminals in the overwhelmingly Hispanic community near Brownsville on the edge of the Laguna Atascosa National Wildlife Refuge

They have notched some David-vs.-Goliath victories. Some insurers and investors have severed ties with Rio Grande LNG. One of the three proposed LNG projects was canceled in 2021.

The most significant legal win came a year ago, when the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit Federal Energy Regulatory Commission approval of Rio Grande and Texas LNG, citing the agencyās failure to fully consider the terminalsā environmental justice impacts, among other things.

But then Donald Trump was elected for a second time.

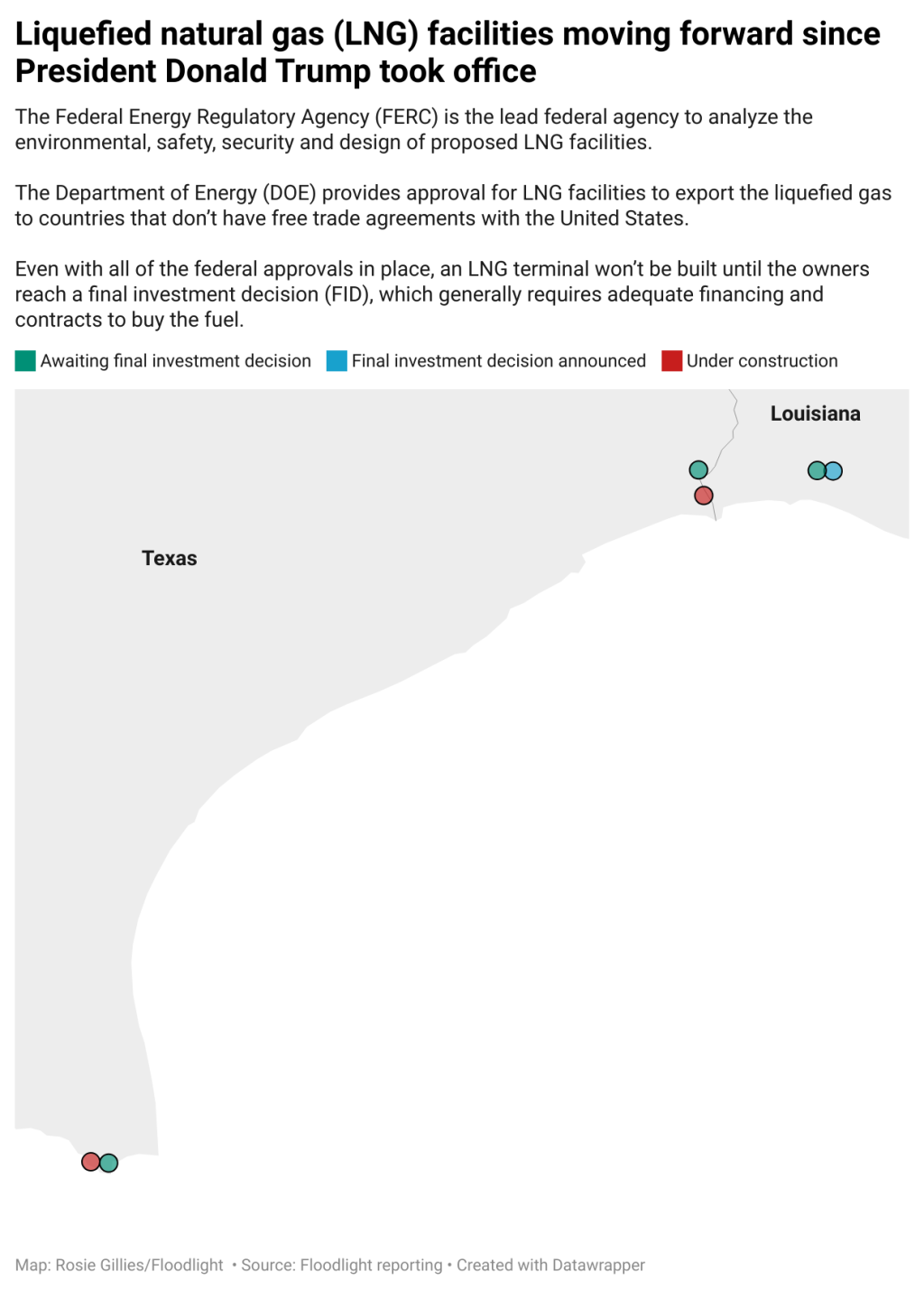

The day he was inaugurated, Trump declared an and rules on environmental justice and protections that had helped groups in Texas and Louisiana fight back. Eight months into his second term, at least six projects that had been awaiting crucial federal approvals ā including those that Hinojosa has fought ā are moving forward again.

And residents along the Texas and Louisiana coasts, from which the vast majority of the nationās LNG flows, face a different kind of emergency, reports.

Fisherman Tad Theriot has seen his yearly income from shrimping in the water near the LNG facilities drop from $325,000 in 2021 to $87,000 last year. This year he estimates the income from his catch will be less than half of that.

āIf ā¦ you donāt get away from Cameron, youāre not catching shrimp,ā Theriot said of the small Louisiana community that already hosts three LNG terminals and where at least two others are planned to be built.

āThey give little peanutsā

The United States has been the worldās largest LNG exporter since 2023. , six terminals are operating, six are under construction, and another six are proposed. The amount of LNG exported ā last year it was 11.9 billion cubic feet a day ā is expected to double by 2028.

The growth is fueled by the nationās vast reserves of natural gas that can be forced out of the ground by hydraulic fracturing, or fracking. Fracked gas is sent by pipeline to an LNG terminal where it is superchilled until itās a liquid and then shipped around the world.

While a million British thermal units (MMBTU) of natural gas can be purchased in the United States for about $4, after itās superchilled and transported across oceans, countries such as Japan and Germany pay $12 to $15 per MMBTU for that gas.

Even after the cost of producing and shipping the LNG, companies that export LNG stand to make billions of dollars in profits. Billions more are made by the middlemen who buy and sell the fuel.

A U.S. Department of Energy finalized in May said LNG creates jobs, expands the United Statesā gross domestic product and helps close the trade gap.

āPresident Trump was given a mandate to unleash American energy dominance, and that includes U.S. LNG exports,ā Energy Secretary Chris Wright said in the report. āThe facts are clear: expanding Americaās LNG exports is good for Americans and good for the world.ā

Developers promise jobs and economic benefits to the areas that host the plants ā although studies show those promises . In exchange, LNG facilities in Louisiana . Louisianaās Cameron Parish alone would forfeit nearly $15 billion between 2012 and 2040 if all proposed terminals were built.

Several companies that produce LNG along the Gulf Coast did not respond to requests for comments for this story.

Local residents, like James Hiatt, founder of the regional environmental and community advocacy group, For a Better Bayou, say the communities do not benefit. Pointing to houses abandoned in Lake Charles after Hurricane Laura five years ago, Hiatt said, āIf they have so much money, why donāt they actually pour that money into the communities where they operate? They give little peanuts. (Itās) nothing to the amount of money that they have been given by the government and the people here.ā

They do get one thing, activist Roishetta Ozane, founder of the Vessel Project, says: pollution. While families struggle to pay for their own energy, Ozane said all the local community gets from the methane buildout is ā.ā The production and transportation of LNG also generates significant greenhouse gas emissions, .

John Allaire, a retired oil and gas engineer, owns land adjacent to the Commonwealth LNG site in Cameron Parish, one of the terminals that has received conditional approval from the federal government. And across the Calcasieu Ship Channel from his property, he can see Venture Globalās Calcasieu Pass 1 LNG, and the site of its expansion, called CP2.

He has watched 90 meters of his shoreline disappear in the past 27 years because of climate-change-caused rising sea levels and subsidence. Burning more fossil fuels, including LNG, will speed the rise of the waters around the terminals ā .

While the terminals themselves will be protected by 26-foot-high seawalls, Allaire and others around the terminals will not.

āThese are the estuaries that supply the seafood that Cameron Parish and Louisiana are so famous for,ā Allaire said, pointing to wetlands near his home where crabs and shrimp lay their eggs. āBut that'll all be backfilled (with) concrete and sheet pilings and tanks. ā¦ Itāll change this environment forever.ā

Is the LNG boom headed for a bust?

LNG is sometimes promoted as a ābridge fuelā because it burns cleaner than coal. But Cornell scientist Robert Howarth warns that its full lifecycle emissions ā including methane leaks during drilling, liquefaction, shipping, and regasification ā is 33% . That claim is disputed by industry, which has produced its own claiming LNG is more environmentally friendly than coal.

The International Energy Agency has that any new fossil infrastructure jeopardizes global climate goals.

The LNG industry its fuel is helping by replacing coal in countries like India. But a from the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis found that India is turning toward renewables, not LNG, to replace coal.

Others are questioning whether demand for the fuel will support the boom in the production of LNG. Export terminals require gas prices of around $8 MMBTU to break even ā far more than the $3 to $5 per MMBTU equivalent of energy that countries like India can afford.

Despite these analyses, developers are touting a booming market. Trump has extracted promises from Asian countries, including Japan and Vietnam, to purchase more LNG, but not all of the deals are binding ā or even new.

Allaire has seen such promises fail in the past. Golden Pass LNG in Texas, Allaire notes, was originally built as an import facility, but is now being refashioned as an export terminal after a pause caused by the the project.

āThey spent billions of dollars, took out hundreds of acres of wetlands, and they imported seven loads of LNG,ā Allaire said, predicting, āThese places will go out of business, and they will be stranded resources.ā

In the meantime, new numbers from the Energy Information Administration, the Department of Energyās statistical agency, indicate the rapid increase in LNG production is increasing the cost of natural gas ā the countryās main fuel source to generate electricity. āThe high demand for gas exports is ā¦ pushing up the price of the gas that supplies 40% of U.S. electricity ā a cost that will be passed on to consumers,ā predicted the .

āItās about continuing to existā

Despite Trumpās aggressive promotion of LNG, Tyson Slocum, director of the energy program for Public Citizen, said there are still grounds to fight the buildout, even if the environmental and justice arguments have been removed by his administration.

āThese additional exports are going to expose Americans to higher gas prices,ā he said. āYou canāt declare an energy emergency where you claim domestic shortages of energy at the same time youāre going to greenlight a bunch of export terminals.ā

For residents like Roishetta Ozane, adding more LNG facilities is not an abstract energy debate. Itās a lived experience of cumulative harm, environmental erasure, and political abandonment caused by the petrochemical industries around Lake Charles, 30 miles north of the epicenter of the LNG development.

āOur community is already surrounded by pollution,ā she said. āIt makes absolutely no sense to approve two or three new LNG facilities here in southwest Louisiana when we already have as much industry as we do.ā

āItās just like a death sentence.ā

Still, both Ozane and Rebekah Hinojosa refuse to give up. In late July and early August, Ozane was among roughly outside companies in New York City that are financing and insuring the LNG boom.

āWe will still keep fighting and speaking up to do everything we can to stop these projects, because our community doesn't want these projects,ā Hinojosa said. āI mean, for us, itās about continuing to exist here.ā

is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates the powers stalling climate action.

was produced by and reviewed and distributed by Ā鶹Ō““.