How race and income can determine the quality of the air you breathe

How race and income can determine the quality of the air you breathe

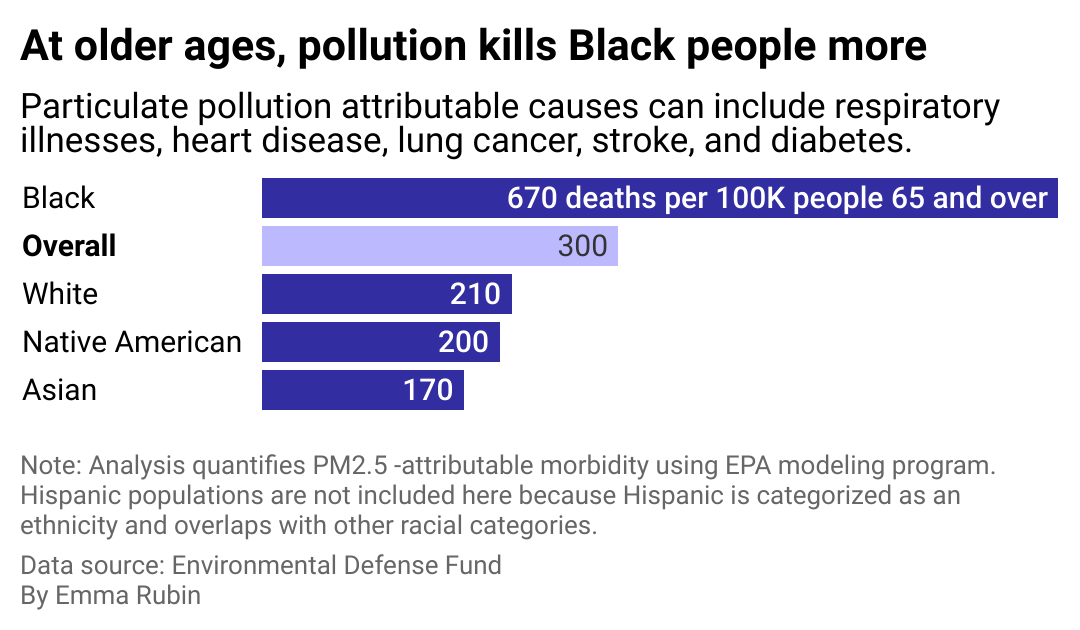

Fine particulate air pollution, or PM2.5, is one of the largest environmental causes of human mortality. PM2.5 exposure is responsible for more than 100,000 premature deaths annually, with Black and Hispanic populations dying at a greater rate than other races.

When inhaled, PM2.5 pollutants鈥攋ust a fraction of the width of a single strand of human hair鈥攃an travel deep into the lung tissue, enter the bloodstream, and increase the risk of cardiovascular disease, respiratory illnesses, and even lung cancer.

Most air pollution can be traced to the burning of fossil fuels, such as gasoline, diesel, oil, and wood. Inhalable particle pollutants form when chemical compounds emitted from industrial sites, automobiles, and other sources undergo chemical reactions in the atmosphere.

Despite average PM2.5 exposure over roughly the last two decades, disparities in exposure to this harmful air pollution persist among populations of color and low-income communities. People of color are exposed to more pollution from nearly every source, including industrial, agricultural, vehicular, construction, and residential sources.

from the University of California, Berkeley, and the University of Washington proves these present-day disparities are largely rooted in a discriminatory housing practice called redlining. Some neighborhoods鈥攐ften those populated by people of color or where an industrial site was already located鈥攚ere given the worst investment risk grades (D) by the federal Home Owners' Loan Corporation. People in D-grade neighborhoods were ineligible for federally backed loans or favorable mortgages and, as a result, could not build wealth through homeownership.

Without the resources and political influence to resist, these neighborhoods became common , as well as industrial facilities and transportation infrastructure built adjacent to or directly through them. More than 80 years later, these redlined communities have consistently higher levels of nitrogen dioxide, a gas found in vehicular exhaust and industrial emissions, and PM 2.5 pollution.

Using data published in the journal and gathered for the , 麻豆原创 looked at disparities in particulate pollution exposure in the U.S.

Over 100,000 people are estimated to die from particulate pollution each year

Black and Hispanic Americans tend to live in neighborhoods with greater exposure to air pollution due to a generationslong legacy of housing segregation. Black Americans over age 65, in particular, experience per capita compared to other races, likely from the combination of increased exposure and greater prevalence of medical conditions like .

The rate of , when broken down by race, was highest in Black and Hispanic patients, according to a 2021 study published by the JAMA Network. While the study does not attribute these cases solely to air pollution, it recognizes it as a potential factor.

Historically redlined neighborhoods tend to be characterized by . Consequently, residents are more vulnerable to the urban heat island effect, which can and increase mortality.

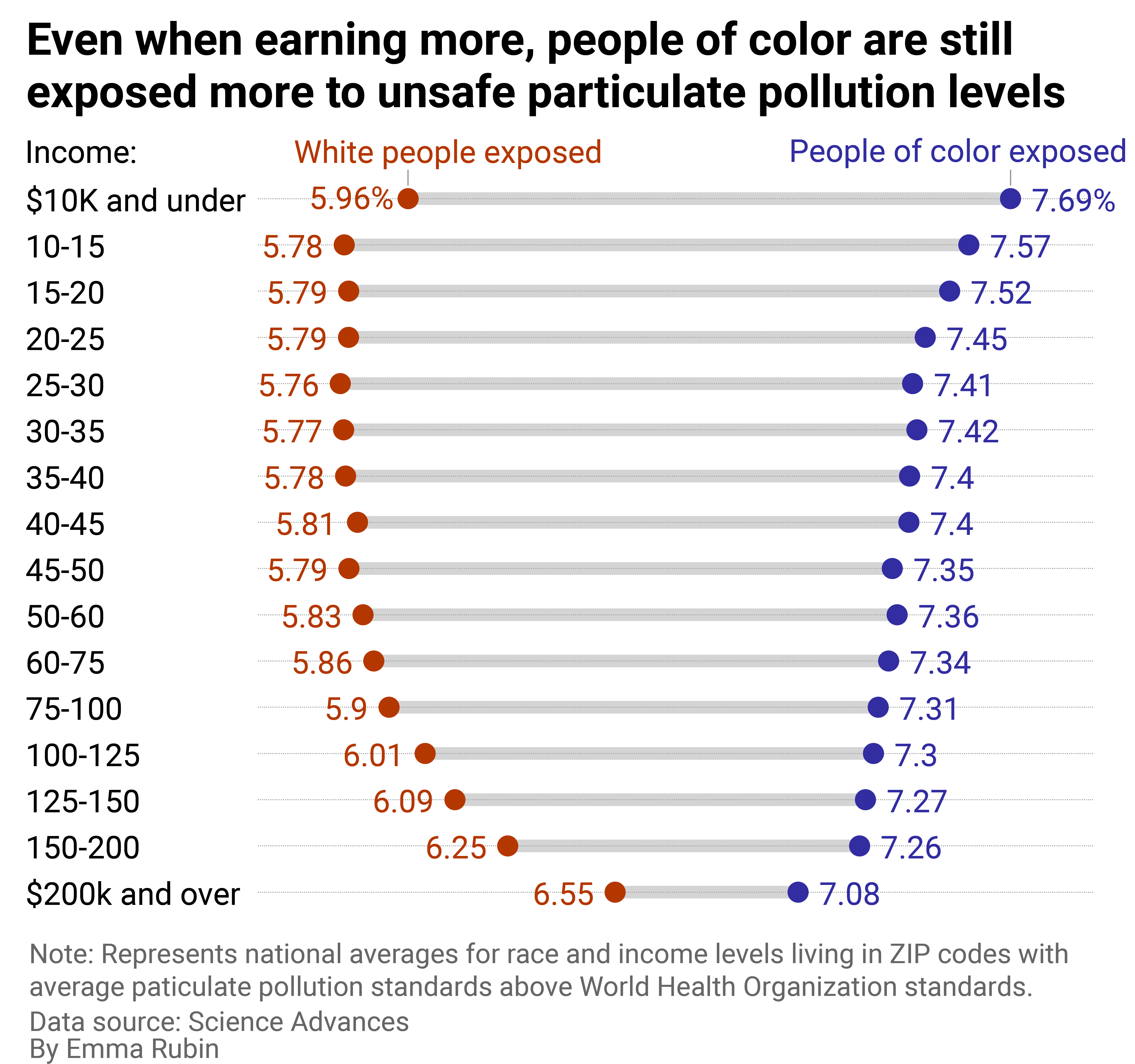

Higher income does not guarantee better air for people of color

In addition to children, people over 65, and individuals with preexisting medical conditions, low-income communities are especially vulnerable to fine particulate pollution due to proximity to industrial sources of air pollution, underlying health conditions, and poor nutrition, among other factors. Low-income populations are than wealthier populations to live in areas where levels of PM2.5 exceed the Environmental Protection Agency's current limit.

The disparity in exposure to air pollution between white people and people of color is reduced as income increases. However, even at higher income levels, populations of color are still more exposed to particulate pollution than white populations.

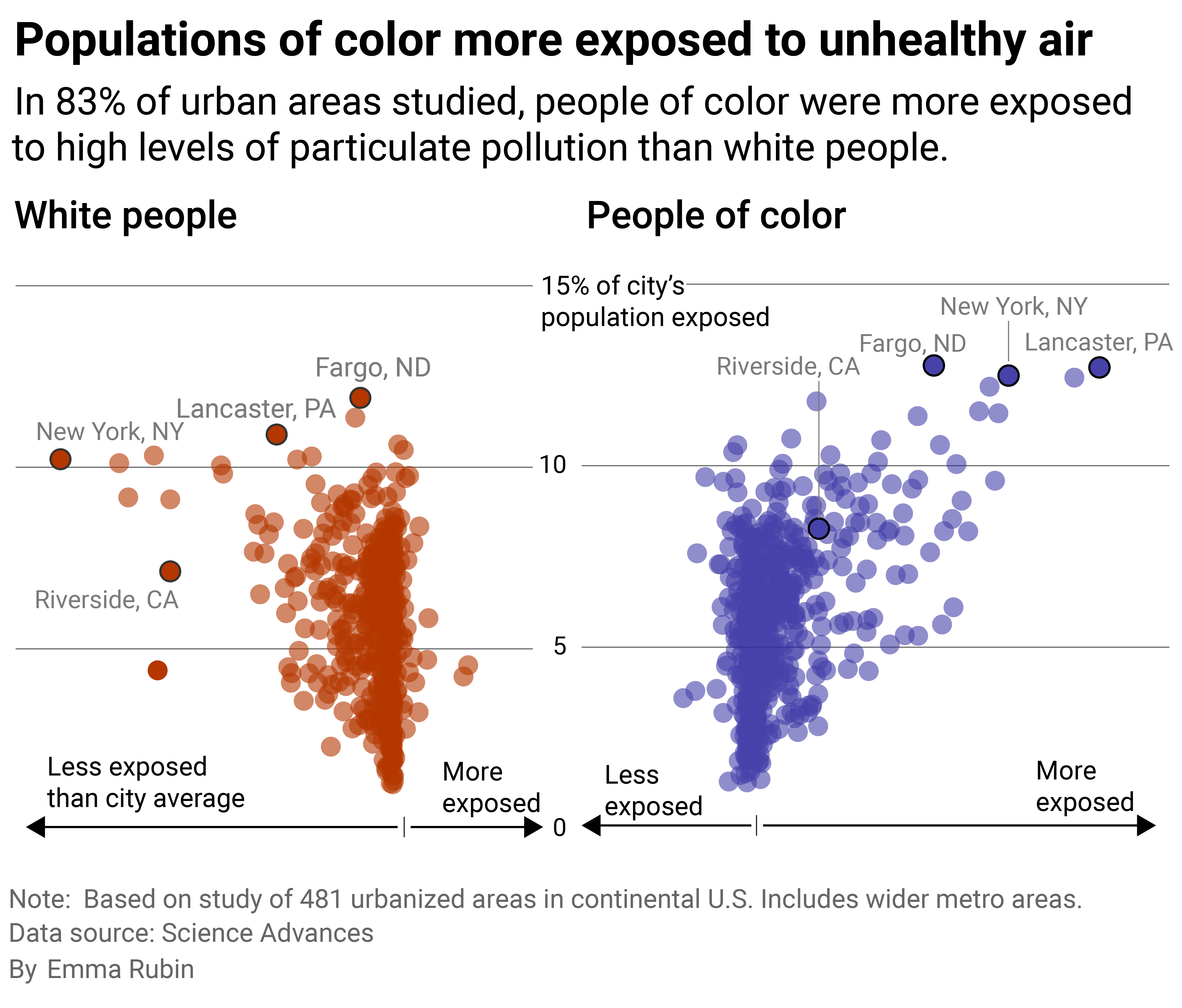

Differences in urban areas more pronounced

Exposure to air pollution . Researchers compared exposure to air pollution by race鈥攚hites versus people of color鈥攁nd exposure based on income levels within populations of color. The disparities in exposure by race were more than double those present when comparing people of color at various incomes.

In rural areas, roughly 5% of all residents are exposed to PM2.5. By race, this breaks down to 4.8% of white people compared to 5.2% of people of color. For Black populations specifically, the share of exposure jumps to 6%.

In urban areas, exposure rates are much higher across the board due to increased proximity to emissions sources and higher emissions volumes. In roughly 400 out of 481 urban areas studied, people of color were exposed to higher-than-average levels of PM2.5 pollution, while white populations saw lower-than-average levels of exposure.

People of color are more impacted but less responsible for emissions

Inequitable exposure to PM2.5 pollution is just half of the problem. Disproportionate emissions by race are the other. A published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences connecting air pollution exposure to consumption of goods and services found that white Americans disproportionately cause air pollution, while Black and Hispanic Americans disproportionately inhale it.

White populations are exposed to 17% less air pollution than they cause. In comparison, Black and Hispanic populations are exposed to up to 63% more air pollution, on average, than the pollution they cause. Industrial and roadway emissions, like light-duty gasoline vehicles and heavy-duty diesel vehicles, are among the largest sources of this exposure disparity.