Progress fighting pancreatic cancer, one of the deadliest malignancies

Progress fighting pancreatic cancer, one of the deadliest malignancies

A diagnosis of pancreatic cancer is devastating news. Though it makes up only about 3% of cancers in the United States, it’s one of the deadliest, and on track for a dark achievement: By 2030, it’s expected to . This apparent paradox is rising because screening and treatments for other cancers have surged ahead, while pancreatic cancer has remained tricky both to identify and to treat, reports.

Nonetheless, there’s reason for hope, says Anna Berkenblit, chief scientific and medical officer for the Pancreatic Cancer Action Network in El Segundo, California, which supports research and helps patients. Scientists are testing new medicines that disable drivers of cancer that were once considered undruggable. They’re training patients’ immune systems to attack tumors once thought to be invisible to the body’s defenses. And they’re harnessing artificial intelligence to catch pancreatic cancer in early, vulnerable stages.

“The goal is to transform pancreatic cancer into a curable disease,” says Andrew Rakeman, vice president of research for the Lustgarten Foundation on Long Island, New York, which supports science on pancreatic cancer. Or, at least, “something that’s survivable, and livable, and can become more of a chronic condition.”

The five-year survival rate for pancreatic cancer is a dismal 13%. That’s partly because pancreatic tumors surround themselves in dense, scar-like tissue, blocking medicines and immune cells. Small tumors advance quickly but often go unnoticed until they’ve , making it too late for surgeons to remove all the cancer.

One of the biggest hopes right now is medicines that target a protein called KRAS, which is part of a cell’s growth-control machinery. In more than 90% of pancreatic cancers, mutated versions of KRAS get stuck in the “on” position, so cells divide uncontrollably.

Cancer biologists would love to shove a stick into the machinery of KRAS, but they’ve struggled to find a place to jam that stick. “People have described it to me as like a small, greasy ball … there’s no kind of pocket to stick an inhibitor in,” says cancer biologist Paige Ferguson of the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York, who cowrote an article in the 2025 Annual Review of Cancer Biology.

So researchers took a different tack: They were able to design a drug that attaches to a different cell protein. That drug/protein duo then grabs KRAS, stifling its dirty work. In an early trial, 38 people with pancreatic cancer receiving the drug, daraxonrasib, , on average, without their disease worsening. Treated patients also had in their bloodstreams.

The drug’s developer, Revolution Medicines of Redwood City, California, is . Results are expected in mid-2026, but the US Food and Drug Administration has already offered .

Progress with vaccines

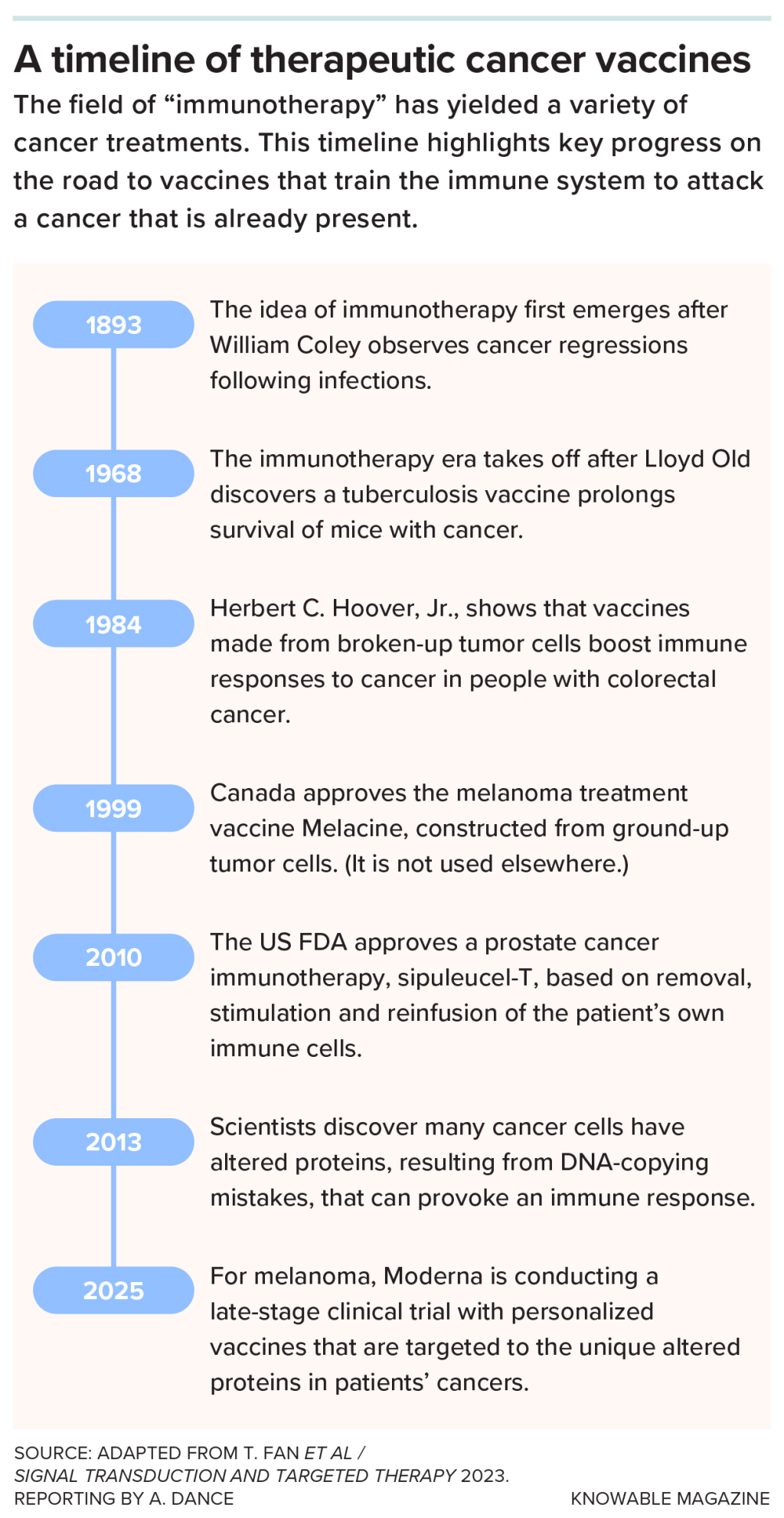

Another approach generating interest is vaccines. These differ from the kinds that prevent infections — they are used in people who already have cancer, training the immune system to wipe out existing or recurring tumor cells.

As with regular vaccines, the cancer vaccine provides a molecule that the immune system sees as foreign and bad. In this case, that molecule is made by cancer cells, so the immune system should go after the cancer. The FDA , for prostate cancer, in 2010, and ones for different cancers are .

Pancreatic cancer resisted early attempts to rev up patients’ immune systems. “It has this amazing ability to keep the immune system out and tell the immune system to leave it alone,” says Rakeman.

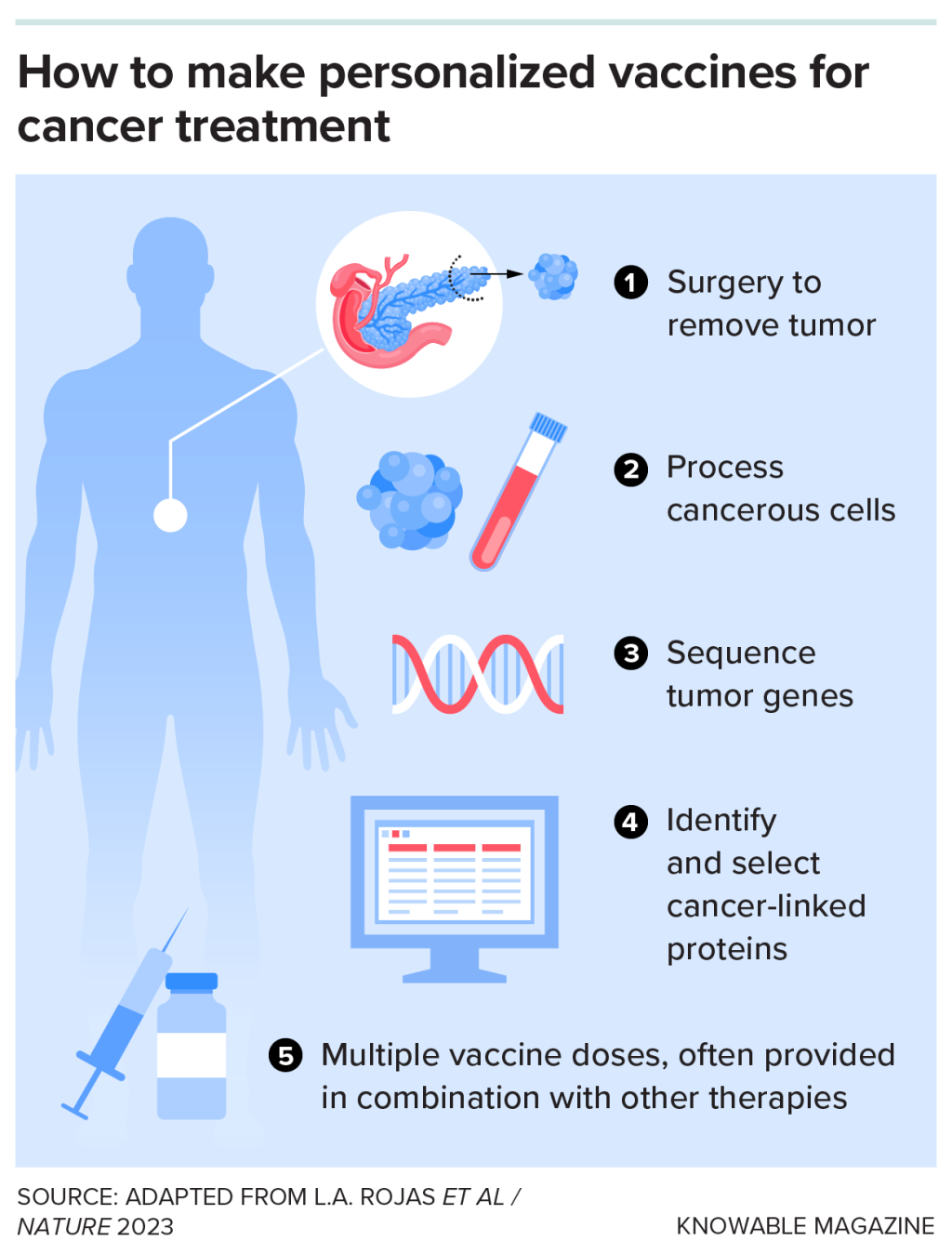

Part of the reason is the dense tissue surrounding the tumor “like a fort,” says Shubham Pant, a medical oncologist at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. But if that fort and the tumor within are removed, the bits of cancer left behind should be unprotected. Pant and his colleagues reasoned that a vaccine might spur the immune system to mop up those remnants.

Working with Elicio Therapeutics of Boston, the scientists tested a vaccine containing bits of two mutant KRAS proteins. This, they hoped, would train the immune system to attack cancer cells containing those mutations.

The team ran a small trial that included 20 people with pancreatic cancer and five with colorectal cancer. Following surgery to remove the tumors, 21 people that were active against their cancers. And 17 patients with the greatest response “tended to do really well,” says Pant. The amount of tumor DNA in their bloodstreams dropped, and 13 remain alive more than three years after their first vaccine dose.

Encouraged, the team developed a vaccine against all seven common KRAS mutations. In a larger trial, they’re .

A different vaccine type has been tested at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York. The scientists first took a close look at the few who live with pancreatic cancer beyond five years — fewer than one in 10 patients, says surgeon-scientist Vinod Balachandran, director of Sloan Kettering’s Olayan Center for Cancer Vaccines. They found that survivors were , but the immune cells weren’t going after mutant KRAS. They were responding to other weird proteins that show up in cancers because the cells make mistakes, creating random mutations. When these mutated proteins end up on the cancer cell surface, it’s a “red flag” to the immune system, says Balachandran.

Balachandran wanted to make this happen in more pancreatic cancer patients. So he and his colleagues provided trial participants with customized vaccines, matching their specific mutations, developed by BioNTech of Mainz, Germany, and Genentech of South San Francisco, California.

In early trials, the vaccines caused against the mutant proteins in eight out of 16 patients, and the T cells . Responders also went longer without recurrence of their cancer than non-responders. And all eight responders survived for at least two years after treatment. A larger, international, trial is underway.

A push for early diagnosis

Another way to stymie pancreatic cancer would be to diagnose it early enough to remove the tumor before the cancer spreads.

Diagnostic companies like GRAIL of Menlo Park, California, aim to do this with pancreatic and other cancers by screening blood for tumor DNA. GRAIL in October at the European Society for Medical Oncology Congress: Of 23,161 people age 50 or older, with no recent cancer, who were followed for at least a year, the test , including pancreatic cancer, that was later confirmed. About half of the correctly diagnosed cancers were early stage.

But the test also made mistakes, suggesting that 83 people had cancer when they didn’t. Even a very good test will give false positives, says Ferguson, and with pancreatic cancer so uncommon, widespread screening would yield many mistakes. So many physicians prefer to screen only high-risk individuals.

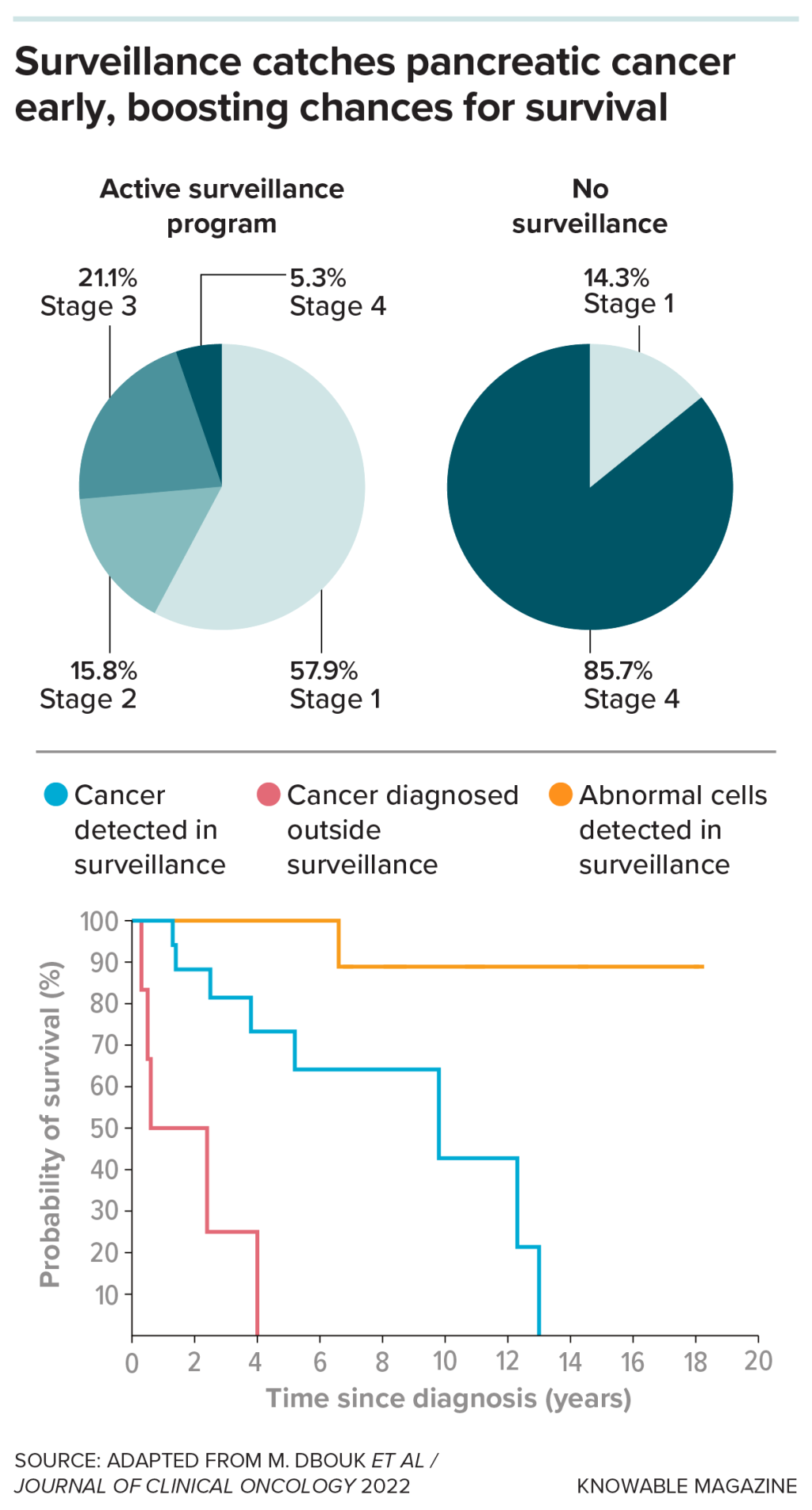

That group includes people with pancreatic abnormalities like cysts and those who carry cancer-linked mutations or have family members with pancreatic cancer, says Venkata Akshintala, a gastroenterologist and pancreatologist at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore. He’s an investigator on the long-running Cancer of the Pancreas Screening Study based at Johns Hopkins and other clinical centers. Its goal is to identify signs of early cancer in high-risk people, via DNA, pancreas secretions or imaging tests.

The screening seems to work. “We usually find cancer in the early stage,” says Akshintala. Of 1,731 CAPS participants, 19 were diagnosed while under surveillance. Their survival , compared to 1.5 years for people who weren’t under surveillance when they got diagnosed, the researchers reported in 2022.

The Johns Hopkins researchers think there’s room for improvement by using AI to recognize patterns associated with pancreatic cancer in the mottled, black-and-white, endoscopic ultrasound patterns that gastroenterologists like Akshintala study for signs of early lesions. Combining AI with physician expertise of a cancer progressing than either did alone, the team reported in 2024 at the Digestive Disease Week conference.

Back at MD Anderson, gastroenterologist Suresh Chari is studying another promising clue for early diagnosis of pancreatic cancer: recent blood-sugar test results that look like type 2 diabetes, often followed by unexpected weight loss. Normally, the pancreas controls blood sugar via release of hormones. But in this case, “the pancreatic cancer is causing your glucose metabolism to go crazy,” says Chari.

In a study of medical records, a risk score incorporating blood-sugar changes and weight loss in seven of nine people who went on to receive the cancer diagnosis, Chari and colleagues found. Most people who scored high didn’t have pancreatic cancer, Chari notes, but the screening narrowed the pool of folks who might benefit from further testing. Based on this research, he’s hoping to test a clinical approach in which those who score high get a one-time, AI-assisted CT scan within 15 days of their blood glucose results.

These tests and treatments in development could mean that pancreatic cancer won’t be one of the deadliest cancers forever. “Within the next 10 years,” says Berkenblit, “I think we’re going to see improved survival.”

was produced by and reviewed and distributed by Â鶹Դ´.