Top science stories of 2025

Top science stories of 2025

2025 was a year of turmoil for many scientists ā particularly in the United States, where job cuts and budget slashing have left many . But it was also a year of promising advances in fields from gene therapy to quantum computing.

In the U.S., executive orders by President Donald Trump led to the loss of thousands of jobs in government agencies, including NASA, which oversees space exploration, and NOAA, which runs the National Weather Service, among other vital activities. Thousands of health-related research grants ā especially those with any perceived link to diversity, equity and inclusion ā were canceled or withheld. And Harvard and other universities saw billions of dollars held back, at least temporarily.

°Õ°ł³Ü³¾±čās for 2026 (the U.S. budget had not been finalized as Knowable Magazine went to press) features huge cuts to science funding, including slicing the budget for the National Science Foundation, the main granting agency for basic science research, in half. And cuts that have already been made spell bad news for global efforts to quash diseases and keep climate change in check.

Amid all the bad news, there have also been lives saved, technologies advanced and some very weird science conducted. Here are some of the things that captured ās attention in 2025.

Vaccine hits and misses

Public health faced big challenges this year. āThere have been enormous changes in 2025, really driven by the current [U.S.] administration and their attitude towards both foreign aid and domestic vaccine policy,ā says epidemiologist William Moss at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and coauthor of an Annual Review of Public Health . The (WHO) in 2025, for example, and said it would , the Vaccine Alliance.

Experts are worried that increasing gaps in vaccination coverage will contribute to further outbreaks of infectious diseases previously thought to be under control. This year, for example, measles surged in North America: Canada lost its āmeasles eliminationā status in November, with cases much higher than anything seen in decades, and the U.S. may follow in 2026. Whooping cough is also on the rise.

Over the past 50 years, immunization has saved an estimated 154 million lives globally. Maintaining that is . The 2020 pandemic caused disruptions to vaccination campaigns, and many have not yet recovered to pre-pandemic levels. Part of the problem is growing anti-vax sentiments. In the United States, has crept downward from around 95% to 92% over the past dozen years, with exemptions from one or more recommended vaccines reaching a record high of 3.6% in the 2024-25 school year. These trends could signal trouble ahead.

There is some good news. After three years of negotiation, delegates to the WHO (not including the U.S.) adopted a Pandemic Agreement with a better system for equitably sharing vaccines and drugs. Coverage with the HPV (human papillomavirus) vaccine, which protects against the sexually transmitted virus that causes cervical cancer in women and some throat cancers in men, continues to increase. And despite the cancellation of $500 million in funding for messenger RNA (mRNA) research in the United States, researchers are increasingly enthusiastic about mRNA vaccines, following on their success during the COVID-19 pandemic. Early research suggests that could be particularly promising in the fight against cancer.

HIV hope ā and setbacks

This year saw some good news on the HIV front. allowed some people with HIV to achieve remissions lasting months or years without the usual daily doses of antiretroviral drugs. And in July, the twice-a-year injections of a long-lasting, highly effective injectable drug called lenacapavir for HIV prevention, following on the heels of U.S. approval for that use. Experts say this marks a momentous shift for people at risk of HIV. WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said: āWhile an HIV vaccine remains elusive, lenacapavir is the next best thing.ā

These new treatments may be especially valuable given the Trump administrationās decision this year to dismantle programs run by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). This includes the disruptions to the Presidentās Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) that delivered a huge and shocking blow to the global HIV/AIDS effort this year. As a result, the United Nations effort UNAIDS ā to which USAID used to be the largest donor ā could be shuttered in 2026, four years ahead of schedule.

All this has left experts and advocates reeling, as the number of people living with HIV ā still one of the worldās most deadly viruses ā continues to climb. that if the PEPFAR funds permanently disappear, there could be over 6 million additional HIV infections and an additional 4 million AIDS-related deaths by 2029. āThe sudden withdrawal of lifesaving support is having a devastating impact,ā said UNAIDS Executive Director Winnie Byanyima at a press briefing in March. āIt is very serious.ā

Spectacular space advances

Astronomers rejoiced as the new , built atop a mountain in Chile, came online this year. The telescope hosts the worldās biggest camera, at 3.2 billion pixels, and is expected to gather more data in its first year than all previous optical telescopes combined. The project aims to catalog some 5 million asteroids, including 100,000 near-Earth objects, over the next decade. It will also help to study dark matter and objects such as supernovae, and pursue new discoveries, including optical signals of gravitational waves. āThe Rubin Observatory promises to impact virtually every area of astronomy and astrophysics, often profoundly,ā says astronomer Robert Kennicutt at the University of Arizona, coeditor of the .

Among the more unusual targets that Rubin will help to spot are interstellar objects ā hunks of rock or ice blasting through our solar system from elsewhere. So far, astronomers have only detected three such objects, including , which made its closest approach to Earth in December. It is suspected that there are many more to find; Rubin could spot dozens over the next decade.

Personalized gene editing gets started

Since the first gene therapy treatment based on CRISPR ā which uses molecular scissors to precisely cut and modify DNA ā was approved in for sickle cell disease, efforts to develop other treatments have ramped up. Therapies are under investigation for a including type 1 diabetes, various cancers and even .

But the big headline this year was the : A baby boy with a life-threatening genetic condition became the first to receive a customized therapy, using a CRISPR-based technique that can precisely edit individual DNA letters. Personalized CRISPR treatments could allow doctors to effectively treat people suffering from rare or even unique life-threatening conditions. Such diseases collectively affect hundreds of millions of people worldwide.

The team behind the baby boyās successful procedure this October their intention to try similar treatments in more children starting in 2026, and in November, the Food and Drug Administration for these procedures. A was also created in July to help families facing ultra-rare diseases. Funded by the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, the center will be led by researchers at UC Berkeley and UC San Francisco. āI know firsthand the heartbreak of telling parents that we donāt understand their childās illness or that we donāt know how to treat them,ā Priscilla Chan, pediatrician and co-CEO of the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, said in a press release about the new center.

Hopes raised for more transplants

This year brought important progress for xenotransplantation, the practice of using donor organs from pigs or other animals for people who need transplants. While only a handful of people have so far received pig hearts or kidneys ā in special cases where they had no other options ā those cases are blazing a trail toward making this technique a clinical reality. āThe numbers are small but mighty,ā says Joseph Ladowski, a surgeon and researcher in transplant immunology at Duke University.

This year brought several experimental transplants of pig organs (including the first lung), with one pig kidney lasting nearly nine months, a new record, before failing. Most importantly, in February the the first multiperson trials of pig kidney transplants, which will allow doctors to standardize and optimize the technique. We should see half a dozen more transplants of animal organs in 2026, says Ladowski, with numbers ramping up steeply after that.

Another exciting development happening in parallel may also help ease the global : using an enzyme to convert the blood type of donated organs, removing antigens that can result in rejection in both human and animal transplants. In October, a team reported the of a human kidney that had its blood type converted from type A to universal donor type O.

Potential treatment for Huntingtonās disease

This year, researchers reported a small but promising study in which they slowed the progression of Huntingtonās disease, an inherited disorder that gradually breaks down neurons, causing uncontrollable movements and a progressive degradation of behavior and thought. The treatment, by the Amsterdam-based company uniQure, is the first to address the disease itself rather than simply easing its symptoms.

Researchers engineered a harmless virus to deliver small molecules called microRNAs designed to block the action of the defective gene that causes Huntingtonās. Then they infused the virus into targeted regions of the brains of 29 patients. In those who got the higher of two doses, the treatment slowed the progression of the disease by 75%, the team found. The result is āa remarkable step forward for patients and families,ā says Andreas Keller, a bioinformatician at Saarland University in Germany who studies potential clinical applications of . āThis is a convincing proof-of-concept.ā

As the climate crisis deepens, renewables get energized

This year continued the growing momentum of the renewable energy transition, thanks in large part to the plummeting cost of solar power. According to an October report from the , the first half of 2025 saw renewable energy provide more than a third of global electricity, squeaking ahead of coal for the first time.

But thatās rare good news in a grim climate picture. U.S. policy, notably, is generally : In a speech to the United Nations in September, President Donald Trump said, āIf you donāt get away from the green energy scam, your country is going to fail.ā

Worldwide efforts to fight climate change are seriously off target, according to the . Global emissions of carbon dioxide may have declined slightly in 2025, but they need to be falling much faster if we are to hit our climate targets. Experts now say we will miss the goal of limiting the warming to , but action can still help to stave off catastrophic consequences to ecology and humankind. āEvery small fraction of a degree matters,ā says Diana Ćrge-Vorsatz, an environmental scientist and climate expert at Central European University and vice chair of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. The put 2025 as the second- or third-hottest year on record, after record-breaking 2024, with an annual average temperature about 1.48 degrees Celsius above the pre-industrial average.

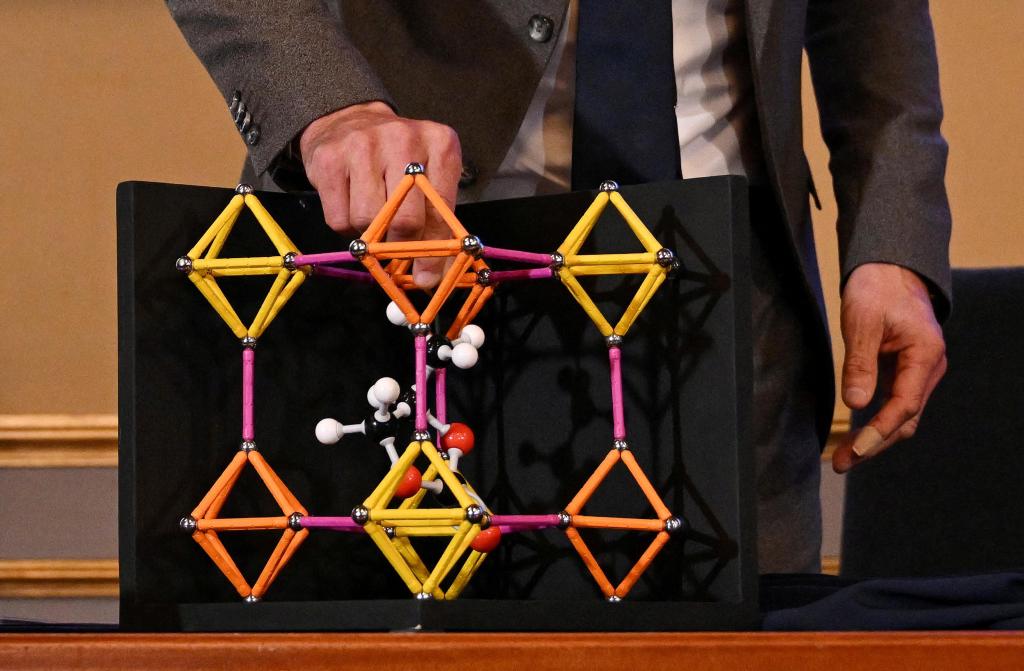

Porous metals come of age

A class of materials called metal organic frameworks (MOFs) hit the headlines this year with , along with the first signs of commercial applications. MOFs are the worldās most porous materials: crystals of metal ions linked by long organic molecules. Their porosity could make these molecular sponges useful as storage containers for gases or drugs.

āMOFs are very elegant, scientifically, and highly versatile,ā says Ram Seshadri, a chemist and materials scientist at UC Santa Barbara and editor of the .

Although they have been a scientific curiosity for decades, MOFs are now starting to in applications ā in part because has massively sped up the hunt for new MOF formulations with desired properties, and in part because of increased interest in sucking carbon dioxide out of the air to fight climate change. This May, a company launched a new factory for making MOF sponges to . Others are investigating using MOFs to in desert regions, to use as a zero-carbon fuel, and even within the body.

Quantum computing gears up

Quantum computing made significant progress this year. Quantum computers are built from qubits, which exploit quantum behaviors to offer faster computation but are also inherently unstable and error-prone. To make a practically useful quantum computer, designers have to create a multi-qubit system that produces a lower overall error rate than seen in the individual bits. There have been a few recent of this ā. And then in October, Google that its āquantum echoesā algorithm proved 13,000 times faster than a classical computer at predicting molecular structures ā one of the first potentially practical applications.

Thatās not the only quantum computing news this year. The 2025 went to some of the foundational research for quantum computing (fittingly, given that 2025 was also UNESCOās ). āQuantum computing is definitely accelerating,ā says William Oliver, a quantum engineer at MIT. āItās pretty exciting.ā

Pollution perils stack up

The global effort to manage pollution faced big setbacks this year. In March, the U.S. announced more than 30 acts of deregulation, many aiming to remove controls it claims were āthrottlingā the oil and gas industries. In August, the EPA its foundational 2009 Endangerment Finding, which concluded that greenhouse gas emissions are air pollutants that endanger public welfare. Rescinding the finding would eliminate the legal basis for the EPAās climate-based regulations. A long list of rules being rolled back is being compiled by , while the Natural Resources Defense Council is tracking .

On the international stage, a hoped-for treaty to end plastic pollution this summer as participants fought over the scope of what the treaty could reasonably cover and the strength of its promises. While negotiations are expected to resume at some point in the future, for now it is up to individual governments to set their own rules for reducing plastic pollution.

Meanwhile, controversial efforts to for minerals took a step forward despite studies showing . Mining in international waters falls under the purview of the , which is developing a to regulate this activity. But in April, the Metals Company sidestepped this process by , which has not ratified the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea that governs the seabed authority. Trump issued an in April to fast-track such mining applications. A final decision is still pending.

Mighty mitochondria: More than just powerhouses

The term āmitochondrial dysfunctionā this year as politicians and researchers alike leaned in to the idea that malfunctions of this subcellular structure may underlie chronic diseases ranging from Parkinsonās to cancer, diabetes and more. āItās becoming more and more recognized that once you perturb mitochondria, a whole bunch of diseases can occur,ā says Andrew Dillin, a molecular and cell biologist at the University of California, Berkeley.

Mitochondria, long called āthe powerhouses of cellsā because they convert nutrients into chemical fuel, turn out to do much more than that. In particular, these little structures inside our cells ā which probably evolved from ancient bacteria ā have , making them a major hub for cell signaling and a big player in regulating stress, immunity and metabolism.

Work this year showed that they can, for example, act as a , detecting invading pathogens and helping the immune system mount a response. Mitochondria seem to be critical for memory formation in immune , have an unexpected role in , and might be targeted to help us .

And finally ā¦

A couple of fun science stories that captured the worldās attention early this year are worth noting, even though some observers have poured cold water on the findings.

In April, Texas-based Colossal Biosciences announced it had genetically re-created dire wolves, a large-bodied wolf species that last roamed North America more than 11,000 years ago. To be precise, the company made 20 genetic tweaks to 14 locations in the genome of gray wolves. about whether this really amounts to re-creating dire wolves, which are thought to differ from gray wolves by about 12 million letters of DNA. (.)

The work āmarks a technical achievement in genome editing and synthetic embryology,ā wrote stem cell biologist Dusko Ilic from Kingās College London in a But, he adds, āwhat has been achieved is not resurrection, but simulation.ā Work continues to āde-extinctā other animals, from the dodo to the woolly mammoth. Whether this is or is a matter of opinion. Other genetic techniques are also being used to try to save living species on the brink of extinction, such as the .

Another quirky headline-grabbing story came when scientists made people see a . Researchers used a laser to directly stimulate just one of the three types of color-sensitive cone cells in the retina: the M cone, which is most sensitive to medium-wavelength light. That never happens in the real world, because any light that stimulates the M cone would also stimulate the neighboring S (short) and L (long) cones to some degree. The five people who experienced this odd light show said the result looked āgreen-blue,ā a color dubbed āoloā by the researchers. The work is a fun exploration of the weird and wonderful world of .

was produced by and reviewed and distributed by Ā鶹Ō““.